Were we to glance back over the last century and beyond, one facet of those now distant generations should stand out: the major public works stamped man-made America. Some easily come to mind, the Erie Canal in 1825, the Croton Aqueduct and Reservoirs in 1842, the five railroads linking Chicago and the East by 1854, a list which counts the Panama Canal, Hoover Dam with its Lake Mead, and the St. Lawrence Seaway. And, among them, we can safely place New York's great Central Park.

To underscore its magnitude we can, for one, point to its cost. When finished in 1887, because there were parts unfinished until then, its improvement is estimated at $10,547,451, excluding the cost of the land needed, $7,389,727.96. A comparison of the time is that of the making of the major Paris parks during and after the Second Empire, $8,000,000. Yet another is the cost of the Paris Opera House, one of the last century's great buildings, over $9,000,000.

In mentioning cost we give the park a new dimension. Admittedly, foreigners once complained about Americans, that we were forever boasting in money terms of our monuments. Still, we would like to underscore this aspect of Central Park, that in today's terms, the cost was well over $400,000,000.

And there is imperial precedence for such boasting, that of Caesar Augustus. Toward the end of his triumphant reign the emperor, who was well aware of Man's frail memory, desired to make certain that what he had accomplished would not be forgotten, nor be credited to others. To this end he recorded the Res Gestae Divi Augusti, the achievements of the Divine Augustus. It was deposited with the Vestal Virgins and, on his death, copies of it were inscribed on monuments throughout the empire. Not only did he list them, but also what they cost because the money had come from his own ample pocket. (The best surviving inscription is in Ancyra, the present Ankara, the capital of Turkey.)

The park's history is familiar. By 1840 New York had a population of 312,000 concentrated south of 14th Street. What was happening in New York, the explosion of cities, was taking place wherever the Industrial Revolution had touched. England, of course, held out the great examples. The spreading factories which produced the urbanizations were being denounced; already the poet William Blake had written of the "dark Satanic mills." So were the agglomerations themselves, and it became only too obvious that something had to be done to provide the equivalent of the disappearing countryside once found outside cities.

The 1840s heard more than one voice calling for a great urban park for New York. William Cullen Bryant, poet and journalist, spoke out in 1844. At the time there were, in truth, only two recognized public pleasure grounds, the one at the Battery and the other at City Hall called "The Park," both minuscule. A second demand came a few years later from Andrew Jackson Downing, the great landscape architect of the Hudson River Valley. By 1850 such was the interest aroused that the question of the city having a proper park was a campaign issue in the mayoralty election of that year. In 1851 the city's Common Council, on the proposal of Mayor Ambrose C. Kingsland, voted for one. Not until 1853 did the municipality obtain authority from the State Legislature to buy the land for "the Central Park" between Fifth and Eighth Avenues from 59th to 106th Streets. (In 1859 it was extended to 110th Street, and the park attained its present size of 843 acres.)

To take charge of the park's construction a city commission was named in 1854 and almost at once adopted an indifferent park plan. Another three years passed and the State Legislature approved yet another permanent body, the Board of Commissioners of the Central Park, and it was this board which took charge of the site and its improvement.

Of course, the site would be nothing but for the transformation. The driving force for the improvement was the vision of the picturesque or natural landscape, very much part of the cult of nature of the Romantic Era. What is more, in this country, the cult was centered in the Hudson River Valley. The great pre-Civil War school of painting was the Hudson River School. Nor was it confined to the artist and writer. The abovementioned Andrew Jackson Downing was the great figure in the landscape art, and not just along the banks of the Hudson. In 1851 Washington called him. He drew plans for the grounds of the United States Capitol, for the Mall north of the Gothic Smithsonian Institution ("the Castle"), and the grounds and parks around the White House. On these last he dealt directly with President Millard Fillmore. If the White House grounds have been much altered, several of the parks which are known collectively as "President's Park" reveal his touch. For example, he gave The Ellipse, to the south of the White House, its basic plan. And he did the same in Lafayette Park to the north of the White House. That he was consulted by President Fillmore gives some notion of his authority. Had he not drowned in a steamboat accident in the Hudson in 1852, he would most certainly have been the planner of Central Park.

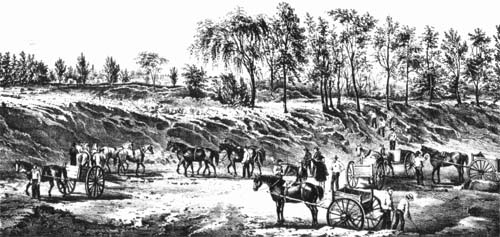

Work on clearing the park began in 1857 just as the Bois de Boulogne in Paris was on its way to completion. At this point there appeared the man who would bring about the park as we know it. Calvert Vaux, the architect associate of Downing, was practicing in the city. English-born and English-trained he had, in addition to his professional skills, a considerable knowledge of landscaping both in England and on the continent of Europe. More, he had a not unimportant asset in being able to paint landscapes. He had worked with Downing in 1851 and 1852, and settled permanently in New York City in 1857.

Vaux's reaction on seeing the original plan for the site, adopted by the second commission as well as the first, was one of anger. He promptly canvassed all those of any authority to oppose it and proposed, as an alternative, one selected by competition. The Board of Commissioners went along with his suggestion.

When the competition was announced in October 1857, he invited Frederick Law Olmsted to join him in preparing a submission. Olmsted, who had been a farmer, nurseryman, writer, editor and even a publisher, had been named superintendent to clear the site. The result was that when he and Vaux joined, he was in charge of several thousand men and had complete knowledge of the terrain. During the day he was in the park, at night he was working with Vaux. The actual drawing of the plan was done in the latter's house at 136 East 18th Street. On April 28, 1858, "Greensward," their design, was named winner. For the record, Olmsted and Vaux's estimate for their project was $1,500,000.

That New Yorkers accepted the estimate to begin with, as well as the subsequent costs, can be seen in the enthusiasm the park inspired with implementation of the plan. Anthony Trollope, the great English novelist who was in this country in 1861 and 1862, recalled it. "But the glory of New York is the Central Park -- its glory in the mind of all New Yorkers of the present day," he wrote. "The first question asked of you is whether you have seen the Central Park, and the second is as to what you think of it. It does not do to say that it is fine, grand, beautiful, and miraculous. You must swear . . . that it is more fine, more grand, more beautiful, more miraculous than anything else of the kind anywhere." While he had his reservation of its being an unrivaled wonder, he did say "But the Central Park is a very great fact, and affords a strong additional proof of the sense and energy of the people."

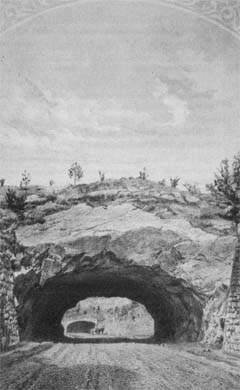

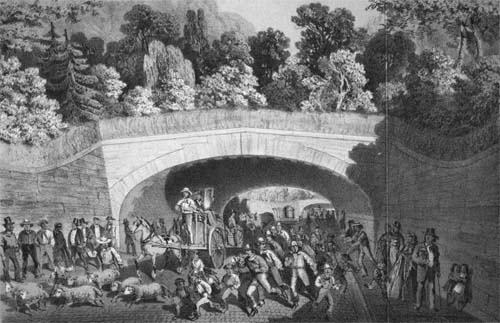

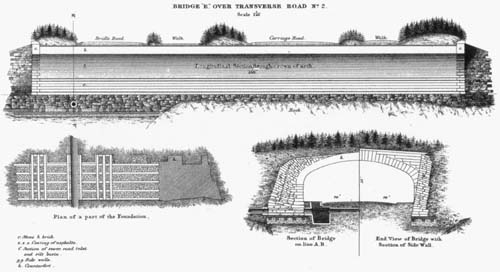

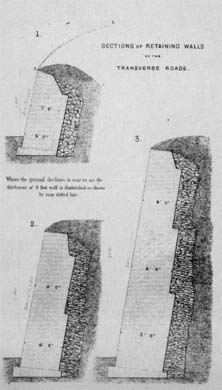

It was Olmsted and Vaux's plan, of course, which excited the public and won the recognition of the novelist. He saw the work not long after long after construction had begun. "At present the Park, to English eyes, seems to be all road," and "the Central Park is good for what it will be, rather than for what it is," were his observations. The key to the designers' success, not just in winning the competition but in gaining public favor, was their innovative solution for the four transverse roads to handle east-west traffic, actually mandated by the Commissioners. They found the answer by sinking the roads and, in this way, taking them out of the park. There were few examples to serve as model prior to their design. One, by the way, is to be found in the sunken streets in the main allée of the park of the Palazzo Reale of Caserta built in imitation of Versailles by Charles III (Bourbon), King of the Two Sicilies. About twenty miles north of Naples it may well have been seen by Olmsted on his European voyage in 1856. If he did notice the Via Camusso beneath the Ponte d'Ercole (Hercules' Bridge) and the Via Tescione near the Fontane di Eolo (Fountain of Aeolus, King of Storms and Winds), there is no record of it in his voluminous papers. Both men actually thought of an example in the zoo in Regent's Park, London.

Whatever the source, the sinking and a tunnel (a tunnel because one had to be carved out of the schist of Vista Rock on the 79th Street transverse), the solution was brilliant. To grasp how brilliant, we need only glance at the failure of the city highway planners of the 1930's and 1940's to follow the Olmsted-Vaux example. A walk in Van Cortlandt Park in the Bronx will make it obvious that much of the Henry Hudson Parkway, as it goes through that magnificent park, could have been given a long tunnel. We might add that the Major Deegan Expressway in the same park could have been given a long tunnel or several tunnels. Yet another sample of the destruction of the same era is found in Cunningham Park in Queens. Admittedly, the answer was not as easy as in Central Park, but the Clearview Expressway could have been so handled that it would not be what it is today, a Chinese wall down the park's center. The Olmsted-Vaux precedent held not the slightest interest to the planning experts of a generation and more ago.

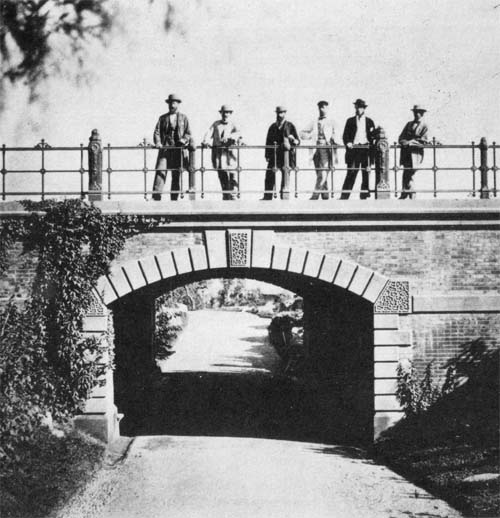

What is most rewarding about the bridges over the transverse roads is their width, an average of 119 feet. Even the ones carrying only a footpath are wide enough to have space for ample planting to screen the traffic below.

These bridges and the one tunnel are, in a sense, not part of the park, any more than the transverse roads. The bridges which count are those within the park proper. The existence of most of those bridges resulted from a major change in the design shortly after Olmsted and Vaux obtained their commission. True, the Greensward plan had drives and footpaths - - few of the latter were indicated in detail -- and few park bridges were shown. The change, and it was made at the suggestion of the Commissioners, was the introduction of a bridle path. When President Washington resided in the city, the nation's capital in 1789 and 1790, he was accustomed to a daily ride until, for reasons of health, he took to a carriage. With the city's expansion the countryside had long disappeared, and riding for pleasure was limited. With the Commissioners numbering such figures as the banker August Belmont, horseback riding, much as carriage driving, was a necessity. Besides, there were the famous examples of London's Hyde Park with its Rotten Row and the Bois de Boulogne of Paris where fashion dictated a daily cavalcade. This meant that, to the drive and footpath, was added a third right-of-way, the bridle path. The two planners had, from the start, mandated a separation of traffic, easy enough to do with two kinds of right-of-way; now a third was to make for more crossings. In the days before the traffic light a bridge was the only answer.

Originally, there were plans for seven bridges, two tunnels, a masonry bridge, and a footbridge within the park and over the transverse roads. Several of these were given up, and wood gave way to masonry. Then nineteen bridges were added, including the Arcade beneath the drive at the Terrace on the Lake. By 1872 there were thirty-four in the park. In addition, two were yet to be built, and at a later date three other bridges were added, one over the bridle path at the West 77th Street entrance, a second at West 90th Street, and a third at Frederick Douglass Circle.

What is astonishing is how successfully the bridges were made inconspicuous if not concealed. The one striking exception is, of course, Bow Bridge over the Lake. For the others the park visitor, unless he or she is an aficionado, has to pause and think where they are to be found. We tend to neglect them because of the traffic lights. Even more, we remain so taken by the park's overall quality of landscape, the lakes and streams, glades, woodlands, sweep of lawn, that the bridges appear only a minor adjunct, when they are works of art in themselves and in their setting.

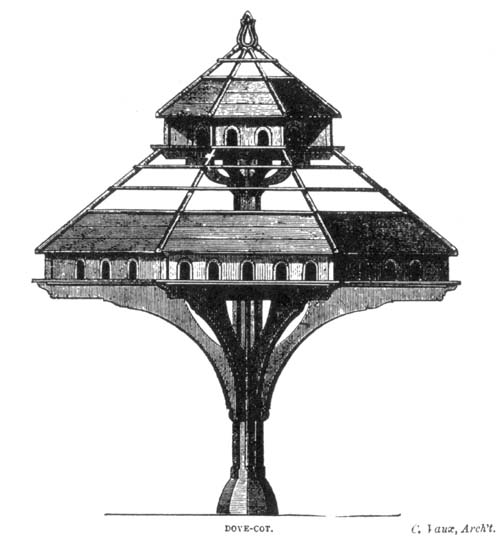

Olmsted and Vaux had a very strong conviction that structures had no place in a park, unless they served a park purpose. For example, they were against having a zoo in the park. If the Belvedere Castle was built it was only because Vista Rock, on which it stands, had disappeared behind a screen of greenery, the Ramble. Vista Rock had served as the focal point of the Mall, and the Belvedere took its place with its tower still to be seen above the trees of the Ramble.

Of course, the bridges threatened to be a major intrusion. For that reason not only did the two planners have to site them for convenience, they had to be placed in such a way that they could not be seen until the promenader was at them. A typical one is Willowdell Arch. How many would know that it exists except for the fact that it is near the statue of "Balto," the legendary Alaskan husky? Siting and building the structure was just part of the work; skillful grading -- to be sure, almost the whole park was regraded -- resulted in concealment.

Hiding the bridges was, in part, a breakaway from the picturesque tradition. In the great English private estates of the 18th century bridges were, along with temples, a conspicuous ornament. Palladio's design for the Rialto Bridge in Venice, never built, was familiar to the landowners as it is found in the Italian architect's Four Books of Architecture, and a number of versions of it can be seen in England. In a sense, Olmsted and Vaux had gone a step beyond their predecessors in their vision of a structureless park, actually achieved by Jens Jensen in the Forest Preserve of Cook County, Illinois, in the 1920's.

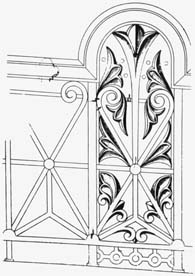

The designing of the bridges fell to Vaux, and it is testimony to his skill that no two of them are alike. This, too, is part of the picturesque tradition with its accent on constant variety. The materials adopted were familiar to New Yorkers of the time: Philadelphia pressed brick (instead

of Husdon River brick); browstone from the Connecticut Valley; sandstone from New Brunswick;* and schist from the park itself. In order to convey a pronounced rustic note he even used several large uncut blocks of schist from the park. The most spectacular example is the Huddlestone Arch, in the park's north end.

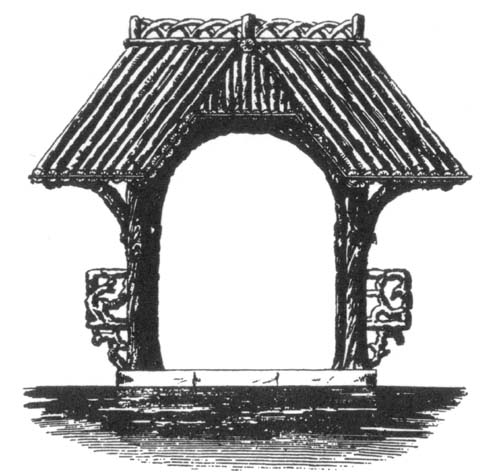

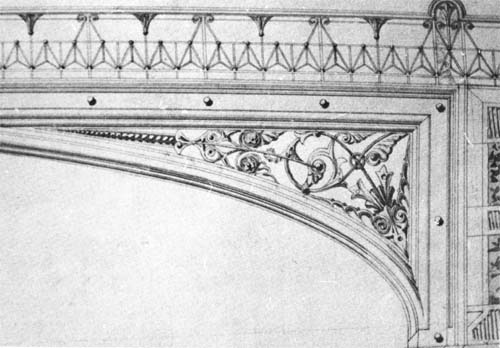

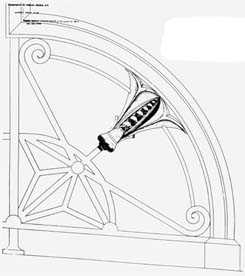

At the other end of the design spectrum are the bridges that are made of cast iron, a favorite of the era, where the architect Jacob Wrey Mould shares honors with Vaux. The parts to be cast would be drawn in exact detail and then sent to the foundry. Large sections, even half an archway, were cast. Cast and wrought iron were innovative. Phosphorous in the iron alloy made fine detail possible in casting. The five remaining bridges in Central Park are outstanding as ornamental iron works in public use. They are also, with the exception of an iron bridge over Dunlap's Creek in Brownsville, Pennsylvania, the oldest cast iron bridges in America.

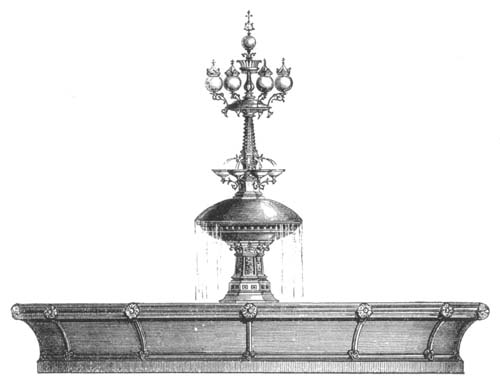

The bridges of Central Park vary in style, although a Gothic and Romanesque note seems to touch most of them. At the Terrace it would appear to be Romanesque with extraordinary realistic detail. The Gothic is to be seen in a beautiful small bridge of cast iron over the bridle path just north of the Reservoir, Gothic Bridge.

They are a constant reminder that the goal of Olmsted and Vaux was to offer as pleasing a contrast as in their power to the city of brick and stone round about. For that reason they were convinced that nature, without artifacts, was the only answer. Any intrusion, unless serving a park use, detracted from the park's environment, to adopt a modern term. The result is that the New Yorker, let us say with Anthony Trollope's permission, can still boast that Central Park is one of the wonders of its kind.