The Men Who Made Central Park

The Men Who Made Central Park

By M. M. Graff

© 1982 Greensward Foundation, Inc. All rights reserved.

| Home | Tours/Lectures | Books | Maps | Posters | Pictures | Contact |

The Men Who Made Central Park

The Men Who Made Central Park

By M. M. Graff

© 1982 Greensward Foundation, Inc. All rights reserved.

The men who created Central Park were visionaries endowed with the highest order of artistry and dedication. The prime movers were William Cullen Bryant and Andrew Jackson Downing. Calvert Vaux, Ignaz Pilat, Jacob Wrey Mould, and Samuel Parsons, Jr., provided the professional experience needed to transform a fetid swamp into a pastoral landscape. How many visitors to the park recall their names with gratitude? Their eclipse came about through an unforeseen circumstance the thirty-five-year-old Frederick Law Olmsted found his ultimate vocation while working on the park site and rose to national fame. The publicity surrounding his later career has overshadowed the gifted men who taught Olmsted his craft. Despite their major contribution to the completion of the first successful venture Olmsted had engaged in, they have been denied due credit if indeed they are remembered at all. In simple justice as well as in the interest of historical accuracy, the record should be cleared of false assumptions and the imbalance corrected.

The inception of Central Park is credited to its two chief proponents, William Cullen Bryant and Andrew Jackson Downing. Beginning in 1844, Bryant printed editorials in his prestigious New York Evening Post in which he urged the purchase of an ample tract for a public pleasure ground before the northward progress of urban expansion made the cost of land prohibitive. Bryant may unwittingly have given the future park its name when he called for "a range of public parks and gardens along the central part of the island."

The second advocate of a city park, Andrew Jackson Downinug, was a nurseryman, landscape designer, author of two seminal books on rural architecture in relation to its setting, and editor of the influential magazine Horticulturalist. Downing's role was doubly formative: he not only stressed the need for an urban park but imported as his partner an English architect, Calvert Vaux, who would be the park's chief designer.

Downing was an enigmatic character who has somehow been overlooked as a fascinating subject for biography. His father was an odd-job gardener with a small nursery in Newburgh in the Hudson Highlands just north of West Point. Young Downing spent his free time roaming the magnificent scenery so glowingly celebrated by the Hudson River School of painters. Downing's special interest was in plants and their effective grouping in the landscape. On one of his botanizing trips, Downing met the Austrian Consul General, Baron de Liderer, who befriended the young plantsman and introduced him to the wealthy, cultivated guests who visited his summer retreat. On these models, Downing built around himself an intricate persona suggesting a Spanish grandee, in which he blended haughtiness, an air of romantic melancholy, and a rigidly guarded self-control which admitted no spontaneous enthusiasm, laughter, or playfulness that might betray what he perceived as a humble origin.

Downing's chief complaint about American rural architecture was that houses were often in conflict with their site. Vaux doubtless echoed Downing's views when he wrote in the second edition of his Villas and Cottages, 1863:

In country houses the design has to be adapted to the location, and not the location to the design, for it is undesirable, and generally impracticable, to make the natural landscape subservient to the architectural composition. Woods, fields, mountains, and rivers will be more important than the houses that are built among them; and every attempt to force individual buildings into prominent notice is an evidence either of a vulgar desire for notoriety at any sacrifice, or of an ill-educated eye and taste.

Downing, an accomplished plantsman and landscape designer, recognized that no amount of horticultural legerdemain could make an ostentatious mansion look at home in rugged mountain scenery. He concluded that the best way to ensure that a house would be compatible with its surrounding landscape was to engage a sympathetic architect with whom to design the two elements as a harmonious unity. Accordingly, Downing went to England in 1850 in search of an architect who shared his views.

George William Curtis describes the meeting of Downing and Vaux in a memoir included in a posthumous edition of Downing's Rural Essays (1856):

He found the assistant he wished in Mr. Calvert Vaux, a young English architect, to whom he was introduced by the Secretary of the Architectural Association, and with whom, so mutual was the satisfaction, he directly concluded an agreement. Mr. Vaux sailed with him from Liverpool in September, presently became his partner in business, and commanded, to the end, Mr. Downing's unreserved confidence and respect.

Downing's choice of Vaux was strangely prescient. He had come to England in search of an architect and acquired, as a bonus, a young man with a knowledge of English and European parks, an intense love of the countryside, and the ability to make appealing sketches of rural scenery -- qualities that would enable Vaux to continue Downing's mission after Downing's untimely death.

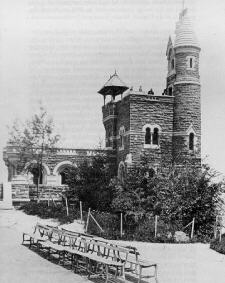

Belvedere Castle. The central canopy has disappeared. The tower's conical roof and elaborately framed window have been replaced by more martial ghost-walk battlements. (Late 19th century photograph. J. Clarence Davies Collection, Museum of the City of New York.) |

George Truefitt, born in the same year as Vaux and student of Cottingham's during Vaux's term, flashes briefly across our screen but leaves an imprint that directly affected the shaping of Central Park. At an unspecified time after Truefitt's five-year apprenticeship was completed, he and Vaux went on a sketching tour of France and Germany. According to Truefitt's obituary, written by his son and printed in the Royal Institute of British Architects Journal for 1902, Truefitt's favorite pastime was sketching both in pen and ink and in color, a form of artistic expression which he pursued with enthusiasm until the end of his life. This is a faint clue on which to base a supposition, but since there is no record of Vaux's having sketched for pleasure, that is, beyond the demands of his profession, it may be inferred that Truefitt was the more practiced and dedicated artist of the two. Whether he taught Vaux to draw, awakened a dormant talent, or refined an existing technique is impossible to determine at this remove. The important fact is that Vaux's aptitude for landscape drawing was to have a significant bearing on the selection of the Greensward plan for Central Park. The Board of Commissioners who judged the competition were bankers and merchants, not likely to grasp the fine points of vistas, focal points, and all^eacute;es as described in the appended notes, but even the least experienced among them could visualize from Vaux's before-and-after sketches how a swamp would become an idyllic isleted lake, an eroded hillside, a flourishing grove.

Despite his theatrical attitude, Downing was no charlatan. He must have had that rarest of qualities, innate good taste, which he refined by studious observation. His preeminence in his field (where, admittedly, he had little competition) is evidenced by his being commissioned in 1851 to design the grounds of the Capitol, White House, and Smithsonian Institution.

Downing's decisive way of dealing with political interference reveals the strength of his character. When niggling critics accused him of extravagance and evasion of duty, Downing asked President Fillmore to summon his cabinet. After presenting his plans and accounts, Downing issued an ultimatum: if his requirements were considered exorbitant, he would roll up his plans and leave. If they were approved, he would finish the job but only if permanently relieved of heckling. One wonders whether the Central Park comptroller, Andrew Haswell Green, a self-righteous miser, would have lightened his relentless persecution of the designers if one of them had stood up to him with equal resolution.

Downing's untimely death in 1852 ended his participation in the project, which was carried out years later by other hands -- including those of Olmsted, who worked on the setting for the Capitol. Even though tragically short, Vaux's association with Downing was richly rewarding. The opportunity to plan a large public pleasure ground under the tutelage of an acknowledged master was to be of inestimable value to Vaux: it gave his professional career the new dimension of landscape design to supplement his earlier architectural training.

Though Downing's chilling aloofness may have seemed forbidding to strangers, it was certainly not employed in the company of trusted friends. Vaux's grief at Downing's death, and the many tributes he paid to his memory, are surely more than the routine ceremony required of a business associate. Vaux designed a marble urn for the Washington Mall in commemoration of Downing. He dedicated the 1867 edition of Villas and Cottages to Downing and his widow, prefacing it with an appreciation of Downing's life and influence. He named one of his sons for Downing; he designed Downing Park in Newburgh under the firm name of Olmsted and Vaux, but probably on his own primary initiative. Last and most important for our purposes, he resolved to make Central Park a fitting memorial to Downing who, with Vaux, would have desired it if he had lived.

Vaux moved to Manhattan in 1857 and at once became involved in the controversy over the design for Central Park. The plan which the commissioners had accepted for lack of a better was the work of Egbert Viele, chief engineer of the park, whose unquestioned competence in the field of road making did not extend to that of art. Viele's design had only two significant open areas -- a parade ground where the Metropolitan Museum of Art now stands and a cricket field in the southwest corner. The rest of the site was a tangle of squiggly roads which cut the meadows into jigsaw outlines. The four transverse roads stipulated in the rules were made to cross the park at grade level, insuring disastrous collisions with carriage traffic on the drives. The five trivial brooks that wandered across the site were left unchanged. The only considerable bodies of water were the two reservoirs surrounded by high walls which isolated them from the overall landscape.

A penciled memo in Vaux's headlong breathless style is preserved in the Manuscript Room of the New York Public Library. It explains both his motives in urging a competition for the design of Central Park as a means of circumventing Viele's botched plan, and his reasons for enlisting the help of Olmsted in preparing an entry for the competition.

Being thoroughly disgusted with the manifest defects of Viele's published plan I pointed out, whenever I had a chance, that it would be a disgrace to the City and to the memory of Mr. Downing (who had first proposed the location of a large park in New York) to have this plan carried out. . . . April 28th 1858 plan 33 "Greenwood" [sic] was accepted by the Board. This design was prepared at my house in 18th Street New York jointly with Mr Olmsted, the drawings being all made at night after the regular work of the day was over.

I first met Mr Olmstead at the house of Mr Downing at Newburgh and was led to ask him to cooperate in the preparation of a competitive design for Central Park partly because I was interested in Mr Olmsted's book "Walks & Talks" but mainly because at that particular time his days were spent on the Park territory where he was in the City's employ. . . . In this way Mr Olmsted, without expense to himself or to me, was so situated that he could bring and did bring to my house where the study was prepared accurate observations in regard to the actual topography which was not clearly defined in the survey furnished to competitors by the Board.

Olmsted was born in Hartford, Connecticut, in 1822. His rather haphazard education in dame schools and under local ministers left him unprepared for any profession. His only strong propensities were for travel and farming. He had an unusually prolonged adolescence, remaining dependent on his indulgent father while he tried a number of unsuccessful ventures. Olmsted had traveled in England and on the Continent as well as in the Deep South and Southwest. His published observations won critical approval but failed to make a profit. The fault probably lay in the ponderous, overstuffed style which Olmsted never learned to animate.

Infused with an idealistic view of farming, Olmsted plunged with initial enthusiasm into the purchase (with his father's funds) of two worn-out properties which he intended to restore. The first, at Sachem's Head, was a small tract of starved, poorly drained land on the sea-scoured coast of Connecticut. Predictably, this proved as unproductive as it was bleak and lonely in winter. When beckoned by the prospect of a walking tour in England, Olmsted eagerly shelved his responsibilities, leaving the care of the farm to his patient father. His second venture was a farm on Staten Island for which Olmsted impetuously imported pear trees. As his father said of him, Fred "goes it strong when he gets hold of a new project." Again, the demands of routine chores became confining. Pears fell off the trees; cabbages froze and rotted in the field for lack of timely harvesting. In the event, Olmsted's growing literary interests induced him to move to Manhattan. In this second and less creditable desertion, he dumped the farm on his unwilling brother John, who was already weakened by tuberculosis.

Olmsted's literary bent led him to invest in a publishing firm which went bankrupt after a few years of bungling management and possible chicanery on the part of the treasurer.

Like Napoleon, Olmsted held the firm conviction that he was destined for greatness. To his chagrin, by the age of thirty-five, he hadn't even managed to support himself, let alone gain the recognition and influence he craved. At this low point in his life -- without meaningful work, ever deeper in debt to his father, and grieved by the imminent death of his brother -- Olmsted was to be rescued by a deus ex machina in the form of a chance acquaintance who told him that the commissioners of the new Central Park were looking for a superintendent of labor, and suggested that Olmsted apply for the post. Olmsted, recalling his delight in the public parks of England, France, and Germany, threw off his despondence and launched a whirlwind campaign to secure the post. His application was approved, perhaps less on the basis of his somewhat inflated account of his experience with agricultural labor than because of the great names of his endorsers, among them Asa Gray, Peter Cooper, Washington Irving, Horace Greeley, and William Cullen Bryant. At long last, Olmsted found something he could do well. He tackled the horde of political hacks, ward heelers, drunks, and lay-abouts with a vigor that shook them out of their do-nothing habits. By firing the recalcitrants and giving promotions and responsibility to those worthy of trust, Olmsted soon had his motley crew hammered into a disciplined work force. The random accident that brought Olmsted into the same field as Calvert Vaux, though by a different gate, was destined to change the face of New York City and ultimately of major municipalities across the nation.

Olmsted's duties as superintendent of labor were admirably adapted to the gathering of precise, detailed topographical information. He was charged with the cleanup of the park site, collecting loose rocks, tearing down squatters' shacks and building a seven-mile boundary wall. His custom of covering the park on horseback enabled him to become familiar with the exact location and nature of every rock outcrop, swamp, hill, and brook. In addition to his daylight surveys, Olmsted would accompany Vaux to the park site on moonlit nights so that they could actually pace over the terrain and solve problems on the site itself.

The winning design was titled "Greensward" because it featured the broadest expanses of lawn and meadow that could be obtained on the narrow rectangular plot. This spaciousness and the flowing curves of drives and walks probably reflect the professional training Vaux received under Downing. The fact that the plan was so neatly tailored to the site that it required little alteration in the building was to Olmsted's credit. The question of the role of each man is the subject of endless partisan argument, no less heated for being essentially unsolvable.

Lack of separation of crosstown commercial traffic and pleasure vehicles in the park was recognized as a major defect in Viele's plan -- at least, as soon as the "Greensward" entry showed how adroitly the problem could be managed. According to Fred B. Perkins, whose Central Park Book was published in 1864 while memories were still fresh, the transverse roads were a deciding factor in the awarding of first prize to the Olmsted-Vaux plan: "So simply and plainly did this device meet the case, that it had much weight in deciding the Board of Commissioners to adopt the plan which contained it. . . ."

Authorship of the sunken transverse roads and of the intricate network of over- and underpasses that kept pedestrians safe from wheeled or equestrian traffic is a fertile subject for controversy. Both Olmsted and Vaux had visited public parks and private estates in England where traffic separation was effected by bridges and tunnels. Vaux, as a Londoner, must have known Alexander Pope's celebrated Grotto at nearby Twickenham. The Grotto was in fact an underground passageway, with walls highly ornamented with shells, crystals, bits of mirror, and other eyecatching decorations, through which Pope and his guests could move from his house to his garden without having to cross the public road that ran between them. Lastly, in the farming country where Olmsted spent his boyhood, pastures that lay on opposite sides of a roadway were often connected by underpasses appropriately call cow-go-unders.

In reference to the traffic system, Vaux, in the undated pencil scrawl quoted above, declared that "it was tacitly agreed between the two designers partners, that no individual claim should be made by either designer in regard to that particular feature -- This agreement I consider binding and adhere to it whenever questioned on the subject." The reader, depending on his partisanship, may decide for himself whether the idea did in truth bloom simultaneously in the minds of both designers or whether Vaux's modest disclaimer was motivated by loyalty to his novice partner.

If the question of credit for this solution of a practical problem must be left unresolved, we do have a telling assessment of the relative artistic gifts of the two designers. It was written by Samuel Parsons, Jr., who retired in 1911 and was the last great plantsman to be associated with the park system. After Olmsted flung off to Brookline in rage and despair at the mutilation of Central Park, Parsons stayed on to fight shoulder to shoulder with Vaux against the predatory pressure groups that plotted to deface it for their special interests. Parsons' judgment is based on intimate knowledge of the two men. He wrote of Vaux: "He, with Mr. Olmsted, perhaps he, even more than Mr. Olmsted, had in my opinion created Central Park. Mr. Olmsted was a leader of men, a man of magnetism and charm, a literary genius, but hardly the creative artist that Mr. Vaux was."

When the plan was accepted, Olmsted, who would have the highly visible job of supervising labor and construction as well as policing the park, was named architect in chief. Vaux, out of the public eye at his drawing board, was appointed assistant to the architect in chief. This reversal of the importance of their contribution -- which, according to Vaux, Olmsted did nothing to dispel -- led to dissension and the eventual breakup of their partnership. It was the first step in the public undervaluation of Vaux's role which broke his spirit and brought him at last to the water of Gravesend Bay.

Jacob Wrey Mould. (Clarence Cook, A Description of the New York Central Park, New York, 1869, p. 50.) |

Mould could work with equal facility in metal, brick, and stone. His bandstand, a polychrome confection in wrought iron, has vanished from the Mall, to be replaced by a hulking mass of concrete and waves of tree-smothering asphalt. However, his Ladies Pavilion, originally placed at 59th Street and Eighth Avenue to shelter people waiting for horsecars, was moved to the Hernshead where it stands after extensive restoration as an endearing example of mid-nineteenth century fantasy.

The Cooper-Hewitt Museum's exhibit of original drawings of Central Park structures brought Mould's mastery to public awareness in 1980. His renderings of purely utilitarian buildings such as the sheepfold and the stables on the 86th Street transverse are drawn and colored with the exquisite detail, taste, and precision thai might have been expended on a tycoon's mansion on Fifth Avenue.

Terrace, looking south. The bandstand was located on the grass panel between the western rows of elms. The Promenade, to which the lady's parasol points, was unobstructed. (Wood engraving after a drawing by A. F. Bellows. Cook, A Description of the New York Central Park, p. 50.) |

It may seem that Mould is given more space in this account of the building of Central Park than the scope of his contribution warrants. The reason is that, of the original designers, he is the only one whose work survives to a substantial degree. Much of the flowing Olmsted and Vaux design has been mutilated or obliterated by encroachments. The Wollman rink, the Naumberg bandshell and its surrounding shroud of asphalt, the Lehman mausoleum, the garish Lasker sitzbath, and the baseball fences that bar the general public from the use of North Meadow have all defaced the original pastoral landscape and turned it into a landlocked Coney Island. Similarly, Pilat's celebrated plant groupings have long ago succumbed to official neglect and incompetence, notably by the failure to clear groves and open meadows of self-sown saplings, and culminating more recently in the scandalous fiasco of planting around the Pond in the southeast corner. Only Mould's artistry stands as evidence of the commitment to beauty, to quality, and to excellence that once motivated all those who created or maintained Central Park.

The Arcade and Bethesda Fountain. (Photograph by Esther Bubley, 1982.) |

Clarence Cook, an art critic much feared for his scathing pen, wrote A Description of the New York Central Park in 1869. It is the most complete if not the earliest commentary on the park in the first stage of its development. . . . The text is augmented by charming wood engravings of the park landscape, peopled by mannerly visitors: ladies in bonnet, shawl, and crinoline with the indispensable parasol to keep the sun from blemishing a delicate complexion, and with solemn children whose wildest excess was tossing bread to the swans and ducks on the lake. The book is priceless as a pictorial record of vanished features such as the Cave, the Marble Arch, and Mould's bandstand on the not-yet-violated Mall.

Cook is an historian's dream: a trained observer with informed taste, a gift of vivid description, and a burning scorn of anything shoddy or second-rate. Because of Cook's unswerving high standards, his praise of Mould and his work carries unquestioned conviction: "He has such delight in his art that it is far easier for him to make every fresh design an entirely new one, than to copy something he has made before." The wellspring of Mould's marvelous invention never ran dry: one can spend an hour examining the decorations on the capstones and side panels of the posts that mark turns in the screen walls of the Arcade without finding a single duplication.

On the upper level, the motifs of leaves and berries are stylized to the point of abstraction, with the exception of the two posts that flank the stairs leading under the drive. The one to the east, which symbolizes Day, has been cruelly vandalized, but it is possible to make out the beams of a sunrise on the east side, vestiges of a crowing cock on the south, and a farm scene on the west. In the background is a thatched cottage with sheaves of grain, a sickle and rake on the ground, and what is perhaps the handle of a shovel against the windowsill, but nothing remains of the foreground figure which may have been the farmer going about his early morning chores. The western post, representing Night, has fared better: on the east side, the student's oil lamp and book are intact; on the south, an owl has been broken off but the bat behind it remains; and on the west side, a witch on a besom flies over a jack-o'-lantern.

In the six huge panels that line the outer stairs, Mould threw convention to the Moors and indulged in some exuberantly flamboyant studies of the plants of each season, alive with insects and birds, many of which have lost their heads to vandals. The extreme eastern panel is a catalogue of spring, with tulips and dogwood blooming on shared stems that loop in swirling arabesques. As Marianne Moore walked down these steps, her keen eye noted "a bird about to pick up a worm (a rather large worm lest it be overlooked)." The medallions in the center of the latticework balustrades continue the theme with flowers in tune with those on the panel above. At the foot of the steps on the east side, the post has a realistic carving of a nest containing four eggs, with the parent bird about to feed the first hatchling which stands in its broken shell.

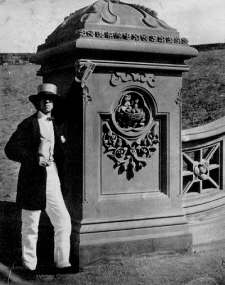

The Bird's Nest Post. The proudly possessive air of the man grasping the newly carved post could only belong to its designer, Jacob Wrey Mould. In this early photograph, the slope is bare of planting. The background has been painted out, perhaps to eliminate the distracting cluttter of building the screen wall on the upper level. (Photograph by Victor Prevost. Central Park in 1862. Stuart Collection, the New York Public Library.) |

On the opposite side of the Terrace, the post at the bottom of the stairs presents two badly damaged birds with wings spread and heads turned towards each other as if agreeing to start off on their migratory flight. The winter panel on the extreme west side above the landing is of particular interest because its motifs are easily identified. Pine cones of various species and sizes grow from the same wildly circling stems as holly and bittersweet, mingled with olive-shaped forms on short thick spurs which can only be ginkgo fruit. Clarence Cook speaks of two "well-grown specimens of the Japanese sacred tree, the Ginkgo or maiden-hair" in the vicinity of Cherry Hill. It is tempting to speculate that one of these may have been mature enough to bear fruit which was duly perpetuated in stone on the panel nearby. Identifying all the plants on these panels would be a fascinating project for a horticultural student, with a further inquiry into how many of them were imported to make a first appearance in Central Park.

The transition from carved stone plants to living ones is easy in theory but painful in fact. So little of the original planting survives that attempting to reconstruct its appearance is like trying to discover from scratched records and static photographs how Caruso sang, how Pavlova danced.

Samuel Parsons, Jr., the articulate, dedicated plantsman who tried to halt the decline of Central Park under the scurrilous administration of Boss Tweed and his followers, gave credit for the subtle beauty of the plantings to Ignaz Anton Pilat.

The original designers, if I may judge from Mr. Vaux, and certainly Mr. Olmsted's knowledge of plants was no more profound, would not in the beginning have enabled them to work out the details of the plantings. . . . The plant expert was Ignatz [sic] Pilat, an Austrian, a landscape gardener* of excellent training and ability, the value of whose services has been largely overlooked. He must have had a great deal to do with the successful planting of places like the Ramble. The paths, lawns, grottoes, caves, and all such incidents were probably constructed under the supervision of Olmsted and Vaux, hut the single specimens of trees could only have been selected and arranged with the help of a plant expert who was also a landscape gardener, like Ignatz Pilat.* "Landscape gardener" preceded its modern equivalent, "landscape architect," a term which Vaux used in official papers after 1862 and which was probably coined by him.

Pilat indeed had a formidable reputation. He had earned his academic degree at the University of Vienna, started his practical training as a gardener at the university's botanical garden, then joined and eventually headed the Imperial Botanical Gardens at Schonbrunn. As an indication of the esteem in which he was held, he was commissioned to lay out a park for Prince Metternich.

Andrew Haswell Green, the tyrannical comptroller who exacted a dollar of value for every penny he grudgingly yielded to Central Park, demanded a report on plantings from Pilat and an explanation of "why certain portions of the planting were treated in a certain way," in Pilat's words. It is doubtful whether Green bothered to read Pilat's eight-page, handwritten letter of April 7, 1862, or was able to comprehend its bristle of scientific plant names. However, in this one instance we can forgive the skinflint Green because his stinginess gives us a first-hand exposition of how Pilat arrived at his selections and groupings in creating landscape pictures.

In his report to Green, Pilat described the entrance at Fifth Avenue and 59th Street in great detail, including the transition from the Drive to the naturalistic plantings around the Pond. He then led the reader north on East Drive, or Ride as he termed it, to the first overpass from which one viewed the northern arm of the Pond.*

* Samuel Parsons, Jr., described this as "one of the best landscapes in the Park . . . a good subtlety for a painting with its details of a chain of rock-bordered pools with the distance rising over grassy banks to a dense background of trees and shrubs." The site is now occupied by the crass vulgarity of the Wollman rink.Pilat went on to describe the atmosphere of the Drive:

The effect already produced and to be perfected in the course of time, throughout the length of the 'Ride,' is that of a pleasant country-road shaded by over-arching trees, mingled with shrubs and vines, spaces being left for more or less expanding views of open lawns, sheets of water, and other objects of interest which give the idea of extent and diversity; hut wherever these open spaces would destroy the harmony of the landscape, a few scattered trees or low shrubs are so arranged as not to obstruct the view.

There are few reminders of pleasant country-roads in the present-day expressways set with highway lamp posts and mostly furnished, when there is any planting at all, with Oriental magnolias, cherries, and crabapples which suggest an alley cutting between backyard gardens. The only stretch of road that still preserves the illusion of a ride in the country is East Drive between 86th and 96th Streets, where magnificent elms arch above the road and in some cases meet overhead. Beyond the 97th Street transverse, the contrast is jarring: the inviting seclusion of East Meadow is laid fully open to the eye, while on the west side, walls of chain link fence make North Meadow look like the exercise yard of a prison -- a far cry indeed from the designers' avowed intention of providing "a sense of enlarged freedom" for visitors to the park.

Pilat's explanation of his treatment of the formal planting on the Mall is an illuminating one for historians who have struggled to reconcile its stiffly ranked elms with the designers' statement that they were "averse on general principles to a symmetrical arrangement of trees." Pilat's solution of how to have a stately avenue and disguise it at the same time is ingenious.

Another previously completed portion of the Central Park is the 'Promenade' and environs. Of this it is perhaps sufficient to say that the arrangement of the surrounding trees is such as to conceal those planted in straight rows, thus only seen from the main path, and when viewed from other points representing an extended Elm-grove and combining favorably with the open lawns East and West of it.

Looking north on the Mall in 1894. Sir Walter Scott and his deerhound are the right, facing Robert Burns across the promenade. (Photograph by J. S. Johnston. J. Clarence Davies Collection, Museum of the City of New York.) |

Samuel Parsons, Jr., warned against the inclusion of statuary in a natural landscape because "The soft, mellow, enticing charm of the grass and shrubs and trees is not increased by the definite outlines of sculpture." However, in the 1870s, statuary appeared on the Mall, perhaps the only place in the park where it can be tolerated except for the Zoo, another artificial environment. The intrusion was due, for once, not so much to aggressive egotists as to the sacred claims of motherhood, following a benign if naive belief in prenatal influence, the conviction that Lofty Thoughts entertained by expectant mothers would impart spiritual or artistic benefit to the offspring. Sir Walter Scott, writing his way out of debt with noble resolve, would evoke a mood of romantic melancholy congenial to the Victorian taste, but roistering Robert Burns -- rakehelly Rabbie, a ranting dog by his own confession -- seems a dubious choice of inspiration even when gazing skyward after a departed light-o'-love. It is equally hard to imagine what virtue was to be imparted to the unborn by the mother's contemplation of the now-forgotten Halleck, who sits with his laurel wreath cocked rakishly over one post of his ornate chair and whose expression of pinched discomfort more likely derives from abrasion of the ears by his cruelly high collar than from the throes of poetic composition.

In the report to Green quoted above, Pilat wrote of the Ramble planting, "The 'Ramble' which was completed nearly two years ago needs hardly any description." This may be less than satisfying to researchers eager for details, but it serves to indicate how popular and familiar that forested area had already become in its brief span of development. An article in the New York Evening Post in 1866 emphasizes the importance of the Ramble in the overall park design and also gives credit for its attractions to Pilat. "The Ramble is at present the very soul of the Park. . . . So far as we have been able to learn, Ignaz A. Pilat is the gentleman to whom the public is indebted for the fine effects in the arrangement of plants and the classification of colors which charm all visitors of taste to the Central Park." By "classification of colors," the writer of the Post article, J. Payne Lowe, may have referred to a technique in which Pilat was said to excel, that is, the "distancing" of views by tricks of aerial and linear perspective. In his Treatise on Country Residences (1836), John Claudius Loudon, one of Downing's most revered preceptors, gave a clear account of the method: "Standing in a certain position in a scene, the coloring is deep, rich and full in the foreground, more tender and mellow in the middle-ground, and softening to a pale tint in the distance."

Pilat's 1862 report to Green indicates that he followed Loudon's directions explicitly. The map that accompanied the report is missing, but from the context it appears that the "Open ground at D" is probably the Sheep Meadow, since the text speaks of an alternate view from Centre Drive, the short roadway along the west side of the Mall now closed to traffic and reserved for roller-skaters. The planting described is seen from West Drive in the area from 66th to 69th Streets.

The trees eastward are combined harmoniously and distinctively in groups, the lighter colored, such as the silver Abele (Populus argentea), the silver-leaved maple (Acer dasycarpum), the Locust (Robinia), and the three-thorned Acacia (Gleditschia), are placed the farthest distant, and the darker colored species of Maples (Acer saecharinum and pseudoplatanus), Tulip-trees (Li riodendron), Hickories (Carya), Ash-trees (Fraxinus), Lindens (Tilia), Elnis (Ulmus), and so forth, are placed nearer the Avenue, so that, looking to the east, the extent of the gradually scattered trees into the extended lawn is apparently increased, giving the observer the impression of the "Beautiful" so characteristically described by Mr. Downing in his well-known work on "Rural Architecture and Landscape-Gardening." Looking the other way, say from the "Centre Drive," the scenery although quite different will not be less pleasing to the observer, the evergreen planting not only concealing the boundary and all west of it, but by its distance giving a softening indistinct background.

Another device for distancing views was to use bold-leafed plants such as rhododendrons nearest the viewer, then gradually reduce the scale of foliage until all detail was lost, seemingly in atmospheric haze. There is a suggestion that Pilat employed this method of extending the actual distance between the Terrace and the focal point of its view, Belvedere Castle. Black locusts, now in sorry condition, riddled by borers, invaded by bracket fungus, and perching on exposed roots like daddy-longlegs on the eroded hilltops on the west side of the Ramble, may perhaps be descendants of trees originally planted there for the sake of their retreating gray-green mist of foliage.

Lake from the top of Stone Arch. The Ramble's numerous open lawns are now obliterated by unchecked growth. (Cook, A Description of the New York Central Park, p. 121.) |

The Ramble abandoned. The northern arm of the lake which lies between the near shore and the distant line of light-toned of willows is blocked from view by a rampant stand of Japanese knotweed. (Photograph by Esther Bubley, 1981.) |

Even the Ramble's luxuriant vegetation was regimented. In 1872, Olmsted ordered "The middle parts of the Ramble in a line from the Terrace to Vista Rock are to be cleared of trees." This sounds a bit extreme, as a stripped corridor would suggest, at least to a modern eye, a railroad cut or the clearing for a power line. In any event, the intent to preserve an unimpeded view was so emphatically stated that it is clear the Park Department hadn't done its homework when it placed a two-armed highway-type lamppost smack on the central axis.

Northern half of Terrace, from the Music-Stand. The Mall's continuous line of elms reached to the screen wall. At the north end, a small gravel plow formed an ingenious fountain whose swiveling arms threw jets of water in animated patterns. The artist anticipated completion of the Belvedere, barely started in 1869, and included the lower structure on the left, which was projected but in fact never built. (Cook, A Description of the New York Central Park, p. 97.)  The Mall in 1982. Most of the trees have been killed or seriously weakened by three layers of pavement -- concrete, asphalt, and hexagonal block -- laid over their roots around inadequate openings. The lamppost stands on the scrupiously established line of view to Vista Rock and the Belvedere. (Photograph by Esther Bubley.) |

You may well ask what Pilat's role was during this formative period in the park's development. Olmsted's 1860 report to the commissioners states: 'Mr. Pilat, general foreman, has charge of grubbing and nursery-work." Surely better use could have been made of a landscape designer to princes, a recent director of a renowned botanical garden, than menial work at starvation wages. Samuel Parsons, Jr., later made a timeless observation: "All the troubles of the New York Park Department have arisen from failure to understand the value of expert advice."

Horticulture is a profession in which no unqualified person ever hesitates to meddle. Olmsted was no exception. Central Park still suffers from the effects of his ignorance of the nature and habits of plant material. His most devastating blunder was precipitated by a train trip across the Isthmus of Panama in September of 1863, which caused him to take off on a tropical extravaganza. In an ecstatic letter to Pilat, Olmsted gave directions on how to transform a North American woodland, the Ramble, into a Panamanian jungle. Ailanthus trees, limbed up high and streaming with vines, would simulate palms. Other recommended exotics were aralia, paper mulberry, and paulownia, all completely incompatible in a northern forest because of their alien leaf character, to say nothing of their invasive tendency. Existing shrubs were to be smothered with clematis and cat-briar, while the rankest constricting vines -- bittersweet, grape, and wisteria -- were to be trained into the tops of tall trees. The significant factor is that Olmsted plunged into this wild aberration without the slightest forethought of its consequences, with no idea that the lianas he admired in the jungle were killing their hosts just as surely as the wisteria he introduced into Central Park would strangle groves of trees and invade meadows by means of its underground shoots.

In 1867, Pilat was invited by Olmsted and Vaux to assist "in the preparation for some detailed planting plans for the Brooklyn Park." If Pilat indeed made the long trip by horse and ferry from his home in Yorkville to Brooklyn, his role in the planting design for Prospect Park must have been brief, for he died of tuberculosis in 1870. Olmsted then had a clear field with no restraining influence to guide him in the selection and placement of plants.

It is hard to believe that a man who had been brought up in the New England countryside could have had so little awareness of the difference in quality between native plants and the showy exotics bred for garden display. In his directions to gardeners in Central Park, Olmsted had repeatedly ordered that "No man is to use the discretion given him to secure pretty little local effects. . . ." Yet, through his lack of feeling for suitability, he committed the very offense he had warned about. One of his primary directives was that "Every bit of work done on the Park should be done for the single purpose of making the visitor feel as if he had got far from the town," but when visitors are confronted with forsythia, Oriental magnolias, or Japanese cherries, the illusion of wildness is shattered and the country landscape shrinks to the dimension of a city backyard.

Olmsted's insistence on prettifying Prospect Park with garden flowers earned him some sharp criticism in the influential weekly Garden and Forest, in the August 1,1888 issue:

It is certain . . . that combinations of plants other than those that nature makes or adopts, inevitably possess inharmonious elements which no amount of familiarity can ever quite reconcile to the educated eye. Examples abound in our public parks, and especially in Prospect Park in Brooklyn, where there is more of nature than in any other great park, and where along the borders of some of the natural woods and in connection with native shrubbery great masses of garden shrubs, Diervillas, Philadelphus, Deutzias, Forsythias, and Lilacs have been inserted. . . . They look not only out of place, but are a positive injuy to the scene . . . especially of scenery intended to produce upon the mind the idea of repose.

Olmsted's rebuttal in the October 24 issue neatly dodges the subject of the complaint, which the editor recapitulates: "Various showy flowered garden-shrubs of foreign origin have been massed among native shrubs growing apparently spontaneously along the borders of a natural wood in the most sylvan part of the park." Instead, Olmsted launches into a longwinded evasion to the effect that a man from New Zealand or the moon wouldn't be able to tell native trees from exotics. Since most of the visitors to Prospect Park came from Brooklyn, not New Zealand or the moon, the argument carried little weight.

Olmsted seems to have had difficulty in distinguishing between "wild" and "native," as he sometimes appears to use the terms as if he thought them synonymous. In this same rebuttal, he calls barberry and privet "among the commonest wild shrubs," though he is aware of their foreign origin. However, he goes too far when he says that "the Ailanthus, the Paulownia, the Pride of China, all introduced from Asia within the memory of living men, are spreading as wild trees and elbowing places for themselves in the midst of our native forests," which seems to imply that an invasive tendency is enough to make an exotic qualify as a native. What is more important, free seeding doesn't guarantee that an adventive will be harmonious in its usurped territory -- and it is the ability of a plant to look at home, to blend with its native companions, and not its place or origin, that determines its fitness in the landscape.

Olmsted was quite aware of his patchy knowledge of plants, acquired by happenstance rather than orderly scholastic training. He vigorously prodded his son Rick to pick the brains of the expert plantsmen who worked at Biltmore, the baronial Vanderbilt estate near Asheville, North Carolina, and especially to learn from Gifford Pinchot, the first professionally trained American forester. In a letter to Rick dated December 23, 1894, Olmsted wrote, "You must, with the aide of such inheritance as I can give you, make good my failings." Poor Rick had as faulty a memory for plant names as his father, and at one point, in utter dismay, planned to shift to zoology. When informed that zoology involved at least as many technical terms as botany, Rick gave in to his father's wishes and served his landscaping firm dutifully if not with dazzling distinction.

However lightly he brushed it off at the time, public rebuke in an authoritative publication like Garden and Forest, under the direction of Charles Sprague Sargent of the Arnold Arboretum, must have made an impression on Olmsted. It is pleasant to report that towards the close of his useful life he indeed had learned how to treat a naturalistic park. His handwritten directions for the development of Seneca Park in Rochester, New York, dated December 1892, are a model of restraint and good taste and should be used as basic principles to govern any corrective landscaping in the country's much-abused city parks.

Where woods are cut through or the edges cut away exposing tall unfurnished trunks plantings should be made to connect foliage with the ground.

Where trees or shrubs are much drawn up by crowding they should be gradually thinned and replaced by new plants, if there are more already growing on the ground which will take the place of the unsuitable specimens.

In planting all appearances of gardening should be avoided, excepting such cultivation as is necessary to establish the plants.

Plants indigenous to the park and vicinity should predominate in the planting, and should be planted into conditions similar to those in which they are growing wild.

Garden forms and exotic plants should as a rule not be used in any part of the park with the exception of the following kinds which are either natives of other parts of the country, similar to natives in character or especially adapted to certain conditions.

The list that follows is composed mostly of utility grade plants, useful and tough if not markedly interesting. There are a few bad choices: common privet, the last resort of unimaginative designers, and Japanese honeysuckle, which Norman Taylor in his Guide to Garden Shrubsand Trees calls "the most pestiferous vine in this book." It may be captious to remark that Olmsted had fallen on the other side of the fence in choosing safe but somewhat hackneyed plants. We should instead be grateful that he had abandoned his former practice of using garden hybrids and that no forsythia, Oriental magnolias, flowering cherries, or crabapples appear on the list of plants to use in a naturalistic woodland. The principles set forth in his memo should serve as a basis for correcting the multiple mistakes that have marred the original concept of the artists who created our first stretch of countryside in a city.

Olmsted's credo, "The Park throughout is a single work of art," is well known -- except to Boss Tweed and his political successors who have defaced Central Park. A single work of art it may be, but not the work of a single artist. It is hoped that these lines will restore in some degree the recognition which was denied in life to Andrew Jackson Downing, Calvert Vaux, Jacob Wrey Mould, and Ignaz Pilat.

About the author

|

She initiated civilian care of trees in city parks in 1967, acted as an early scout for trees suffering from Dutch elm disease and inventoried the woody plants in the Ramble in Central Park.

As head of the Tree Program for the Friends of the Parks, she selects trees in need of surgery or special attention and insures that care is provided through the Camperdown Fund. Because of her efforts, many ailing trees have been saved, including the famous Camperdown Elm in Prospect Park, which inspired a poem by Marianne Moore, founding president of the Friends. Mrs. Graff designs the many new plantings undertaken by the Friends, and is the major reporter for its newsletter, A Little News.

Her ranging interests in plants is reflected in her books, Flowers in the Winter Garden, Tree Trails in Prospect Park, Tree Trails in Central Park, Rock Trails in Central Park (with Thomas Hanley), and Peter Malin's Rose Book. She has written articles for House and Garden, Horticulture and Flower & Garden. She continues to write for Flower & Garden.

An interest in photography grew naturally out of her appreciation of visual space as defined by plantings. Her photographs have appeared in the Brooklyn Botanic Garden's Plants and Gardens as well as in the books she has authored.

Although difficult to believe of one whose two speeds are "sleep and a dead run," she has retired from private consulting. Happily she continues as guardian of our public trees and as a gardener, writer, and photographer.