| Home | Tours/Lectures | Books | Maps | Posters | Pictures | Contact |

|

JPEG, 7" x 11", best for viewing on screen (2 megs, 72 dpi) JPEG, 7" x 11", best for printing (7 megs, 300 dpi) PDF, 7" x 11", also best for printing (7 megs, 300 dpi) |

| Notable Trees of Central Park Shown on the map above is a selection of Central Park's notable trees. Beginning in 1969 the Friends of Central Park have given professional care to many of them and to hundreds of other trees as well. This work, made possible by generous contributions from concerned citizens throughout the country, saved irreplaceable trees from the ravages of neglect and environmental stress, and set the standard for the extensive tree care program that the Central Park Administration had undertaken and continues today. |

by Henry Hope Reed

Central Park is the largest park in the center of a great city. No other park its size, 840 acres, two and one-half miles long, is so accessible. There are ten subway stations on its borders, and a dozen or more within comfortable walking distance. Bus lines encircle the park. No wonder that it is visited all year long, a treasure of discovery in walks, lakes, meadows, and woods.

With all of the city's towers of brick, stone, and glass around it the visitor, once in the park, is surrounded by greenery. Few paths lead straight into the park. Instead, they bend away from the entrance, and the city for a moment disappears. At one entrance the path drops to the shore of a pond. At another a wisteria arbor welcomes. Glade, copse, and rock outcrop offer a constantly changing landscape. Water takes different forms -- ponds, streams, and cascades. The ever-changing scene extends to planting. A shagbark hickory (Carya ovata) calls to mind the variety of native flora, as does a sour gum (Nyssa sylvatica), supplemented by foreign species such as the Himalayan pine (Pinus wallichiana) or a flourishing horse chestnut (Aesculus hippocaslanum).

So triumphant is the setting that we ever honor the park's designers, Calvert Vaux and Frederick Law Olmsted. Their genius in shaping nature is everywhere. How grateful we are that they sank the transverse roads to keep traffic out of the park. Or, where there was need for a bridge, that it was so designed not to intrude on the landscape. Even when they laid out the one formal area of the park, the Mall, to receive the promenading crowds, they placed it with a climax view of woodlands. The elm-lined Mall leads to the magnificent Terrace and Arcade, and to the Lake with the Ramble beyond.

The Ramble? In an era such as ours, so preoccupied by questions of environment, the Ramble, with abundant and variegated planting, is at the heart of this manmade landscape. Bird life, which had disappeared, returned. Today Central Park is a major pause of migrants on the Great Atlantic Flyway. Bird watching, especially in spring and fall, is one of the rewards of the great park. Nature, given care and maintenance, renews itself and flourishes.

In wandering through the park, the visitor may ask how it all came about. From where did the vision spring? Step into the Metropolitan Museum of Art to come upon the source, pictures by two Frenchmen and one Italian of the 1600s. Claude Lorrain and Nicolas Poussin created their ideal landscape of the ancient Romans, and Salvator Rosa his conception of bucolic nature. Very popular, their work inspired a new style of landscape design, variously called the picturesque or the English garden. Such was the popularity of the Romantic landscape that it would seem all of England and parts of western Europe would be given over to "natural settings." The poet William Cullen Bryant called us to "list to Nature's teaching." This country was hardly half a century old when the fashion for the picturesque wrought a new world along the Hudson River Valley.

Under the Act of the New York State Legislature of July 21, 1853, New York City began setting aside acreage for a park. Calvert Vaux, an English-trained architect, persuaded New York's park commissioners to hold a competition for the central park's design. He then urged Frederick Law Olmsted, park superintendent, to join him in submitting a plan, which they did on April 1, 1858 under the name "Greensward." They won. Creating the new park became one of the country's largest construction projects.

Among the reasons the site was chosen was that it contained one reservoir and that land had been set aside for a second as part of the Croton water system that supplied New York City. Certainly the terrain was uninviting, with the detritus of glacial drift and with outcrops of Manhattan schist in contrast to the soft, rolling hills of Prospect Park that Olmsted and Vaux would lay out less than a decade later. The designers had to transform the terrain, remove boulders, blast away vast quantities of rock with black powder, and bring in thousands of wagon loads of topsoil. Fewer than twenty species of trees and shrubs were growing on the site. Olmsted and Vaux, with the guidance of Ignaz Pilat, a Viennese plantsman, introduced hundreds of species. The engineer George Waring installed an elaborate system of drainage. Calvert Vaux, the supervising architect, allowed himself some fantasy, not just at the park bridges, but at the Terrace. Here, for the park's most important architectural structure, he was joined by a colleague, Jacob Wrey Mould, the architect who created its decorative features. Mould was steeped in Spanish architecture. As a young man, he had made a detailed study of the Alhambra. For the Terrace he introduced Moorish detail and, with a flourish, designed elaborate Minton encaustic tiles imported from England for the ceiling of the Arcade, which are unique in the world.

In 1858, when the Greensward plan was approved, the park's northern boundary stopped at 106th Street. Five years later 65 more acres were added, bringing the total acreage to 840 in order to include, as proponents of the park had urged, the "series of bold and picturesque rocky bluffs, terminating abruptly at 110th Street, which offer the only natural boundary to the Park property." (A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening by the late A. J. Downing, Esq.; sixth edition, 1859.) It was not the only change that came about in the park's early years. To the plan's footpaths and carriage drives Olmsted and Vaux added bridle paths to provide a third means to enjoy traversing the park.

Another extraordinary aspect of the Greensward plan was the almost total absence of buildings. The Arsenal, today's headquarters for the Department of Parks, predates the park but was not in the original design. Inevitably over the decades, however, brick, stone and mortar would rise within the boundaries. At first, animals donated to the park were kept at the Arsenal, but later, as more animals arrived, a menagerie was built and then expanded. A sheepfold was added on the west side of the park. The most conspicuous early structure was the Belvedere, the Victorian Gothic castle that arose on Vista Rock in 1871 to provide a focus to the view from The Mall, the original focal point, Vista Rock itself, having disappeared behind the growing woods of the Ramble.

Invasions were held at bay in the last century, but with the 20th century, change took on momentum. Sports had to have special grounds. Children's recreation called for playgrounds. The automobile, allowed in the park in 1899, required new access roads. Asphalt replaced gravel. In the 1930s the famed Marble Arch, made of marble from Tuckahoe, New York, was demolished as the drive was widened and straightened. Two cast-iron bridges, Spur Rock and Outset Arch, disappeared. Considering the ever-growing population of Manhattan, it is astonishing that more intrusions did not find their way into the park.

In the 1890s, with the coming of the City Beautiful movement, glass structures for the cultivation of plants became part of park development across the country. In 1899 a large conservatory was built on the site of today's Conservatory Garden at 104th Street and Fifth Avenue. A plant house had been considered earlier, but never built, for the area that now is Conservatory Water near 74th Street and Fifth Avenue. Central Park's conservatory did not last. It was taken down in 1934, leaving Manhattan the only borough in New York City today without a greenhouse.

Perhaps the most dramatic change at the turn of the century was not in the park itself but on the periphery, the tall buildings. One result of the new skyline was lighting in the park. The apartment dwellers on Central Park West (there was only one apartment building on Fifth Avenue) complained of having to look upon a sea of darkness at night. The result was the placing of lampposts throughout the park, designed by Henry Bacon, architect of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C. (The only portion of his lamppost that has survived is the post; the head is modern.) Each park lamppost has a number plate: the first mark the nearest cross street.

In 1929 a conspicuous change was the emptying of the old Receiving Reservoir, to be replaced by the Great Lawn six years later, which became the largest athletic field in the park. There were other, smaller changes in the 1930s: fencing and "keep off" signs were removed; the Sheep Meadow lost its sheep; and the sheepfold, enlarged, became the Tavern-on-the-Green; the Zoo, which had a temporary look, was enlarged and made permanent. A continuing change came with the Metropolitan Museum of Art. It has expanded until it is, today, one of the largest art museums in the world. The biggest change in terms of vistas was the construction of two skating rinks, one in 1951 in the Pond at the south end and another in 1966 in the Harlem Meer at the north end.

As for the landscape, while reflecting surfaces of water have become smaller, there has been a tremendous growth in planting. The park in the 1920s, compared to the present, would seem bare. At that time, London plane and privet were the favorite tree and shrub. The pine had virtually disappeared. Beginning in the late 1960s the pine came back in the pinetum at the Great Lawn. Variety in planting, so much part of park design in the last century, has gradually been restored.

For all the changes, not a few of them protested over the years, greenery has unified the park. A theater is concealed by a row of Berlin poplars. Maintenance buildings are screened by pine trees. The rural landscape, spirit of the vision of the park, has its resources and its strengths. To cherish it ever will keep alive Olmsted and Vaux's concept of rus in urbe, country in the city. Were Central Park not the acclaimed success that it has become, New York would not be what it is today.

|

Horizontal (541K, better for browser viewing) Vertical (547K, better for printing) |

| Los Árboles Más Notables del Parque Central En este mapa se puede encontrar una selección de los árboles más notables del Parque Central. Desde 1969, los Amigos del Parque Central han cuidado profesionalmente de muchos de estos árboles y de cientos de otros. Su trabajo, posible gracias a la generosa contribución de ciudadanos responsables de todo el país, ha salvado árboles irremplazables de los estragos causados por la negligencia y el medio ambiente, y ha establecido las normas del programa del cuidado de los árboles que la Administración del parque emprendió y continúa en el presente. |

by Henry Hope Reed

El Parque Central es el mayor parque en el centro de una gran ciudad. No existe otro de tal tamaño, 340 hectáreas y cuatro kiloómetros de largo, que sea tan accesible. Hay unas diez estaciones de subterráneo en la misma periferia del parque y una docena más a corta distancia. Asimismo, por sus alrededores circulan varias líneas de autobuses. Fuente inagotable de sorpresas con sus senderos, prados, lagos y bosques, no es extraño que sea visitado durante todo el año.

Pese a estar en medio de rascacielos de ladrillo, piedra y vidrio, una vez dentro del parque, uno se encuentra rodeado de puro verdor. Algunos senderos conducen directamente al interior del parque, pero la mayoría discurre bordeando las entradas y, a menudo, la ciudad desaparece. En una de las entradas, el sendero llega hasta la orilla de un estanque. En otra, una glicina da la bienvenida. Los matorrales, los claros y las rocas que salen del suelo, crean un paisaje siempre cambiante. El agua forma estanques, arroyos y cascadas. El arbolado contribuye a la variedad del paisaje. El nogal (Carya ovata) y el gomero americanos (Nyssa sylvatica), hacen inmediatamente pensar en la diversidad de la flora nativa, aquí complementada con especies importadas, entre ellas, el pino de los Himalayas (Pinus wallichiana) y el florido castaño de la India (Aesculus hippocastanum).

Este paisaje extraordinario se lo debemos a los diseñadores Calvert Vaux y Frederick Law Olmsted, cuyo genio para esculpir la naturaleza se evidencia por todos lados. Así, es de agradecer que ubicaran las carreteras que cruzan el parque por debajo del nivel del mismo para mantenerlo separado del tráfico. Cuando fue necesario construir puentes, se diseñaron de manera que se integraran en el paisaje. Más aun, a la hora de diseñar el único espacio para ceremonias del parque, el Paseo (Mall), que acomodaría a la multitud de visitantes, lo ubicaron con una vista espleéndida de la arboleda. Flanqueado por olmos, el Paseo conduce a la magnífica Terraza (Terrace), al Porche (Arcade) y al Lago (Lake) con el Barranco (Ramble) al fondo.

¿El Barranco? En una época como la nuestra, tan preocupada por los problemas del medio ambiente, el Barranco, con su numeroso y variado arbolado, se encuentra en el corazón mismo de este paisaje creado por el hombre. Las aves, que habían desaparecido del parque, han vuelto. Hoy, el Parque Central forma parte de la ruta de las aves migratorias que siguen la Gran Ruta Atlántica. Observar los pájaros, especialmente en primavera y otoño, es otro de los placeres que ofrece el parque. Cuando se cuida y se mantiene, la naturaleza se renueva y florece.

Al caminar por el parque el visitante probablemente se pregunte cómo fue concebido. ¿De dónde surgió la idea? La respuesta se encuentra en el Museo de Arte Metropolitano, en los cuadros de dos pintores franceses y un italiano del siglo XVII. Claude Lorrain y Nicolas Poussin recrearon el paisaje ideal de los antiguos romanos y Salvador Rosa desarrolló el concepto de la naturaleza bucólica. Muy popular en su época, la obra de estos pintores inspiró un nuevo estilo de diseño paisajista llamado pintoresco o de jardín inglés. El paisaje romántico alcanzó tal popularidad, que parecía que toda Inglaterra y parte de Europa occidental iban a llenarse de "decorados naturales." El poeta William Cullen Bryant decía que habiía que escuchar "la voz la naturaleza." Norteamérica apenas contaba con medio siglo de existencia, cuando la moda de lo pintoresco hizo surgir un nuevo mundo en el valle del río Hudson.

De acuerdo a una ley aprobada por el estado de Nueva York el 21 de julio de 1853, la ciudad de Nueva York comenzó a reservar terrenos para edificar un parque. Calvert Vaux, un arquitecto educado en Inglaterra, convenció a los encargados de los parques para organizar un concurso de proyectos para el parque central. Luego, persuadió al inspector de parques, Frederick Law Olmsted, de que prepararan juntos un proyecto para presentar al concurso. El uno de abril de 1858, ambos ganaron el concurso con el plan "Greensward." La construcción del nuevo parque fue en aquel momento uno de los mayores proyectos del país.

Una de las razones por las que se eligió el lugar, fue porque ya existía un depósito de agua y se había reservado terreno para construir otro, como parte del sistema Croton de abastecimiento de agua a la ciudad de Nueva York. Es cierto que el lugar no era muy atrayente, lleno de detritos glaciales y de pizarra saliendo del suelo de Manhattan, en contraste con las suaves y onduladas colinas de Prospect Park, sobre las cuales, Olmsted y Vaux diseñaían un parque en la década siguiente. Vaux y Olmsted tuvieron que modificar el terreno, sacar piedras, dinamitar vastas cantidades de roca y traer miles de vagones llenos de tierra f6értil. En ese entonces, había menos de veinte especies de árboles y arbustos en el lugar. Olmsted y Vaux, con el asesoramiento de Ignaz Pilat, un horticultor vienés, introdujeron cientos de nuevas especies. El ingeniero George Waring instaló un complejo sistema de desagües. Calvert Vaux, el arquitecto supervisor, dejó volar su fantasía, no sólo en el diseho de los puentes, sino también en la Terraza. Para ésta, la obra arquitectónica más importante del parque, Vaux contó con la colaboración de su colega el arquitecto Jacob Wrey Mould, quien se encargó de la decoración de la misma. Mould poseía amplios conocimientos de arquitectura española. De joven había estudiado detalladamente la Alhambra. En la Terraza introdujo detalles mudéjares y, en un gesto de ostentación, para el techo del Porche (Arcade), hizo un elaborado diseño estilo Minton, con azulejos de colores únicos en el mundo importados de Inglaterra.

Cuando se aprobó el proyecto Greensward en 1858, el parque limitaba al norte con la Calle 106. Cinco años más tarde, a petición de los proponentes del parque, se anexionaron unas 26 hectáreas a fin de incluir "la serie de pintorescas rocas escarpadas que, terminando abruptamente en la Calle 110, ofrecen el único límite natural del parque" (Tratado de la teoría y práctica de la jardinería paisajista, del difunto A. J. Downing, sexta edición, 1859). Con la anexión, el parque alcanzó las 340 hectáreas. La extensión hacia el norte no fue la única modificación que se hizo durante estos primeros años. A los originarios senderos y caminos para carruajes, Olmsted y Vaux agregaron senderos para la equitación, como un tercer medio de disfrutar el recorrido del parque.

Otro aspecto excepcional del plan Greensward era la ausencia casi total de edificios. El Arsenal, hoy sede central del Departamento de parques, ya existía antes de construirse el parque, pero no estaba incluido en el diseño inicial. Inevitablemente, a medida que fueron pasando los años, se levantaron varias estructuras de ladrillo, piedra y argamasa dentro de sus confines. Al principio, los animales donados al parque se mantuvieron en el Arsenal pero con el tiempo, al aumentar el número de los mismos, se hizo un zoológico que más tarde se ampliaría. En el sector oeste del parque se construyó un corral para ovejas. Entre los primeros edificios, el más visible era el Mirador (Belvedere), un castillo gótico victoriano erigido en 1871 sobre la Roca de la Vista (Vista Rock), para servir de foco visual desde el Paseo. Con anterioridad, la Roca de la Vista había sido el foco visual, pero ahora la Roca había desaparecido tras la tupida arboleda del Barranco.

En el siglo pasado se logró que los edificios no invadieran el parque, pero con el siglo XX llegaron los cambios. Faltaban campos de deportes y parques para los niños. Los automóviles, con acceso al parque desde 1899, necesitaban nuevos caminos de acceso, con lo que el asfalto reemplazó a la grava. En la década de los treinta, a fin de ensanchar y hacer más recta la carretera, se demolió el famoso Arco de Mármol (Marble Arch), construido con mármol de Tuckahoe (Nueva York). También se eliminaron dos puentes de hierro fundido, el Roca del Espolón (Spur Rock) y el Arco de la Entrada (Outset Arch). Si se considera la población en continuo aumento de Manhattan, lo asombroso es que no haya habido mas intrusiones en el parque.

En la década de 1890, cuando surgió el movimiento de la Ciudad Hermosa (City Beautiful), se construyeron invernaderos por todo el país. Inicialmente, se pensó en hacer uno en el sitio hoy ocupado por las Aguas del Invernadero (Conservatory Water), cerca de la Calle 74 y la Quinta Avenida.

Finalmente, un gran invernadero, construido en 1899, en el lugar hoy ocupado por el Jardín del Invernadero, (Conservatory Water) en la confluencia de la Calle 104 con la Quinta Avenida, fue demolido en 1934. Por esta razón Manhattan es el único distrito de la ciudad de Nueva York que no tiene su propio invernadero.

Probablemente, los cambios más notables a principios de este siglo no ocurrieron dentro del parque, sino en su periferia, donde se construyeron rascacielos. El resultado inmediato que trajeron consigo los nuevos edificios, fue la iluminación del parque. Al oeste (pues solo había un edificio de apartamentos en la Quinta Avenida), los residentes de los apartamentos se quejaron de que por la noche el parque, contemplado desde arriba, parecía un mar de oscuridad. El resultado fue la instalación en todo el parque de postes de alumbrado diseñados por Henry Bacon, el arquitecto del Memorial a Lincoln en Washington D.C. Lo único que sobrevive de ellos es el poste propiamente dicho; la lámpara es moderna. Cada poste tiene una placa con un número, cuyas primeras cifras indican cuál es la calle más próxima.

En 1929 un cambio notable fue el vaciamiento del antiguo Depósito de Agua (Receiving Reservoir). En su lugar, seis años más tarde, se construyó el Gran Prado (Great Lawn), con el tiempo el campo de deportes más grande del parque. En la década de los treinta hubo otros cambios menores: se quitaron las vallas y los carteles de "No pisar" o "Prohibida la entrada." El Prado de las Ovejas (Sheep Meadow) se quedó sin ove

jas, y el corral de las ovejas, una vez ampliado, se coinvirtió en la Taverna en el Prado (Tavern-on-the-Green). El zoológico, hasta entonces provisional, se amplió y se hizo permanente. El Museo de Arte Metropolitano, expandido hasta el punto de ser hoy uno de los museos de arte más grandes del mundo, fue el origen de cambios continuos para el parque. En cuanto

a las vistas, el mayor cambio ha sido la construcción de dos

pistas de patinaje, una en 1951 en el Estanque (Pond), en el

extremo sur del parque, y la otra en 1966 en el Mar de Harlem

(Harlem Meer), en el extremo norte.

En cuanto al paisaje, mientras que la superficie dedicada al

agua se ha visto reducida, la vegetación ha aumentado considerablemente. Comparado con el parque de hoy, el parque de los años veinte nos parecería desolado. En aquel entonces,

el falso plátano y el ligustro eran el árbol y el arbusto preferidos. El pino prácticamente había desaparecido, pero a finales

de los sesenta se planta el pinar de la Gran Pradera (Great

Lawn). Así, gradualmente se ha logrado restablecer la variedad de especies característica de los parques del pasado siglo. A pesar de los cambios, muchos de los cuales no fueron aceptados en su momento, la vegetación ha servido de elemento unificador al parque. Un teatro se esconde detrás de una hilera de álamos. Los edificios para el mantenimiento apenas

se vislumbran detrás de los pinos. El paisaje rural, alma del

parque, posee fuerza y riquezas propias. Si lo cuidamos, siempre se mantendrá viva la noción del rus in urbe, campo en la

ciudad, de Olmsted y Vaux. Si no fuera por el éxito clamoroso

que el Parque Central ha alcanzado, Nueva York no sería lo

que es hoy en día.

| Altrusa International, Inc. of New York Homeland Foundation Josephine Bay Paul and C. Michael Paul Foundation Arthur Ross Foundation Roverta and Irwin Schneiderman Michael Tuch Foundation Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Foundation Edwin L. Weisl, Jr. The West Village Committee Members of the Friends of Central Park and in memory of Dora A. Dennis Richard Edes Harrison Robert F. Wagner, Jr. Estelle Wolf |

A Topographical Map with Delights, Past and Present

New York Times, Sunday, April 17, 1994

Of course, one great joy of a walk through Central Park is an absence of purpose or destination, a willingness to let oneself be drawn off course by an unexpected vista.

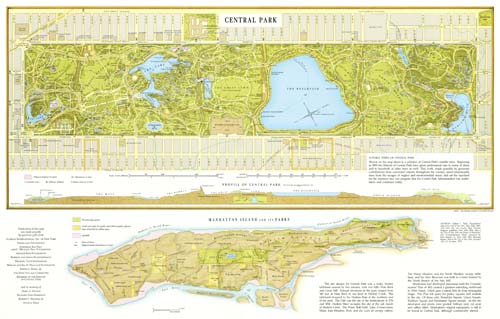

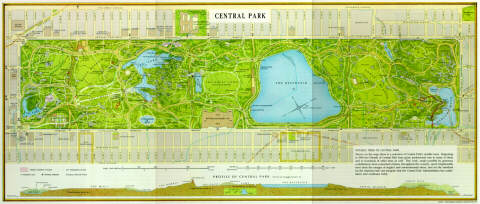

But those who seek more in the way of navigational aids will probably rejoice in a colorful new map of Central Park that shows its features in delectable detail: hills and meadows, pathways and arches, buildings and bridges and bodies of water, prominent rocks and notable trees -- a turkey oak near West 92d Street, a Carolina silverbell near East 76th Street. Topographical contours are given in four-foot intervals.

The map even shows former bodies of water that are now filled in (the Ladies Pond, the Lily Pond and the Loch) and pinpoints long-lost landmarks like the Marble Arch, the Casino, Forts Fish and Clinton, McGowan's Tavern and Nutter's Battery. As a practical matter, it locates the subway stops on the park's perimeter, as well as major buildings that border the 840 acres.

Below the main map is a view of Central Park in profile, from the turreted tip of Belvedere Castle atop Vista Rock to the bottom of the Harlem Meer. A secondary map shows the location of present and former parkland on Manhattan Island. Accompanying the maps is a brief history of the park's development written by Henry Hope Reed, formerly curator of Central Park.

The map was drawn by George Colbert and Guenter Vollath, who have also collaborated on a map of Prospect Park, and published by the Greensward Foundation and the Friends of Central Park.