|

|

||||||

| Excerpts: | ||||||

|

![]()

From "Tender"

From "Tender"

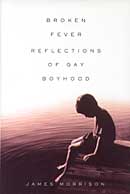

from Broken Fever

By James Morrison

My own first experiences of money, as of so many of the roles of symbol, occurred in church. At every mass I was given a quarter to drop into the wicker basket that was held out, pew by pew, at the end of a long wooden pole, like a holy broomstick, by a deacon who passed from row to row, or else to deposit into a more portable container that passed from hand to hand among the congregants. I much preferred the baskets at the ends of the poles, brandished humbly by the deacons themselves, since that procedure seemed so much more ritually endowed, so much less worldly, than the baskets passed awkwardly, discommodiously, among yawning, snuffling, mumbling church members -- as if the whole thing were nothing but a slightly tedious game of hot potato. When these baskets came to me, I could still feel the sacramental thrill of offering as I dropped my coin into its modest bower of other coins and random bills, but it was when the deacon held out the basket at the end of the wooden pole, and I piously relinquished my coin into that more exalted receptacle, that I truly felt the surge of devotion. Then, it seemed I was transacting directly with the divine, dropping the coin, as it were, right into the unbloodied wound of Christ's eternal body, by which he had saved me from sin. And the exchange was gloriously reciprocal, like the magical commutations of a gum machine, where the plunk of a coin and the crank of a knob produced the colorful, sugary bliss of the gumball. So, in church, I received the consecration of a brittle little slab of host, took Christ's body into my own body, and gave in return the wafer, bright or dull, of a coin.

But the offering was never really mine to give. The money belonged to my father, who did not go to church. Whenever I ventured to ask why not, my mother replied, in a tone that was unreadable to me, "He's Lutheran." Awaiting the circulation of the baskets, I would sit between my mother and my sisters in the high pews, clutching the warmed coin in a tight fist, palms moist with the worry that God, a Catholic, would from upon the offer of the Lutheran's coin. The exultation I could still bring myself to feel on dropping the coin into the sacred plush of the basket came more and more to merge with the fear that followed the offering: if God did not accept my coin, would He refuse me? I could no more imagine the fate of that coin than I could really fathom the source of my father's money. I knew only that I, called on somehow to enter these networks, was still outside of them; my participating was strictly a matter of gesture, of ritual. I imagined one of God's minions hunched among vast heaps of coins, biting down on the surface of mine, like a Dickensian miser, to test its mettle, and finding it wanting, in spite of my pale wish that the clammy lamina of my touch might linger, anointing the coin's face with the fervor of my hope. Thought I must have absorbed by then Biblical edicts regarding the falseness of money and the sinful pride of accumulating it, these coins felt real as I held them in my hand, and in my experience the basest matter was still more visible evidence than the highest manifestation of spirit. As so often in devotional experience, in Eisenstein's drawing shame and supplication are one -- the cowed figure at once advancing and withdrawing, taking the risk of oblation, yet flagellating herself in the bow of her head, a gesture beyond humility -- and the shape of the coins mimics that of the shape of Christ's wounds. I had no money of my own; my piggy bank was always empty, not just because of the feverishness with which I spent money as soon as I came into it, but because the piggy bank itself, actually a leering porcelain monkey (I was reputed to like monkeys) with a dark gash in its belly, frightened me with its uncanny aspect. Though I looked with terror on the prospect of spending my life inside buildings of somber brick with big green doors and high translucent windows, I knew that, in any case, I could never really be welcomed in such places. The world did not owe me a living, as my father took to instructing me from the age of nine onward, and as I grew, the sound of my offering falling to rest in its commissioned place faded from the resonant echoes of veneration into the dingy, meager chink of lucre clattering against geld.

Copyright © 2001 James Morrison

Back

to the Stonewall Inn

Back

to the Stonewall Inn