|

|

||||||||

|

The Editors' Introduction |

||||||||

| Poems: | ||||||||

|

Letter From the Editor

![]()

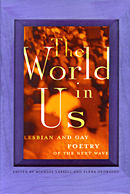

The Editors' Introduction

The Editors' Introduction

By Michael Lassell and Elena Georgiou

The book you

hold in your hands has its roots in the active voice of poetry. It was

conceived in a random moment of enthusiasm at a reading of gay and lesbian

poets, one of a series curated by the Publishing Triangle, the organization

of lesbians and gay men in publishing. The venue was the New York Public

Library's historic Jefferson Market branch in Greenwich Village, the room

that was once the city justice system's courtroom for women — in

fact, the very room where the radical activities of such diverse foremothers

as Mae West and Emma Goldman had been judged to be criminal. We were so

impressed by the quality of the poetry we had been hearing that night,

and on many other nights, that we agreed there just had to be some way

to make a book full of the best poetry being written now. The World

In Us is the result.

As we began to prepare the proposal we eventually submitted to Keith Kahla at St. Martin's Press, we came across the following:

I see the life of North American poetry at the end of the century as a pulsing, racing convergence of tributaries — regional, ethnic, racial, social, sexual — that, rising from lost or long-blocked springs, intersect and infuse each other while reaching back to the strengths of their origins. (A metaphor, perhaps, for a future society of which poetry, in its present suspect social condition, is the precursor.)

This passage, from Adrienne Rich's award-winning What Is Found There: Notebooks on Poetry and Politics (W.W. Norton, 1983) brought together all our own feelings in a concisely poetic summary of "verse" at the end of the twentieth century. These words from a doyenne of the lesbian/gay/bisexual/transgendered (LGBT) community — as the locution now runs — are notable not only for their insight and wisdom but for their literary and social optimism. Rich's life and work stand as conjoined symbols for a unity of poetic and activist purpose, and the affectionate respect she has earned both in the mainstream and in her queer community are a measure of her success in communicating her aesthetic/ethic of inclusion and integration.

This passage perfectly captured our experience at that Jefferson Market Library reading nearly two years ago. What Rich wrote is what we are trying to say with our title. The World In Us is not just an invitation to enter the world that our minority poetry has become as the millennium turns, but a statement — one we believe is supported by the work — that by ourselves we contain the world. We hardly need a place at anyone's table, when our own dining room is full to bursting.

Historically, the waning years of centuries have been times of unrest and uncertainty, and, this, lamentably, is as true of the last months and weeks of the twentieth century as ever before. But we choose to cast our lot with optimism — and Adrienne Rich — because two of Rich's most salient points seem particularly true of the poetry being written now inside the tribe: Queer people are meeting the uncertainties of the future with a flood of poetic energy, and the poetry is coming from as heterogeneous a group of people as the population of the country we all inhabit.

By the time Carl Morse and Joan Larkin edited the landmark Gay and Lesbian Poetry in Our Time for St. Martin's Press in 1988, there was already a considerable literary context for the book, openly homoerotic poetry from Sappho to Frank O'Hara, although through much of its history, our poetry has been closeted, covert, coded. By 1988, there was also far too much material for one book, even with small selections from many of the poets. Many of the writers included in Gay and Lesbian Poetry in Our Time were literary lions, both living and dead. Remarkably, the world of queer poetry has changed dramatically since 1988. Its personnel has changed radically, and the mood is palpably different.

It is difficult to remember a more receptive moment for poetry. The art not long ago deemed both irrelevant and unsalable has been taken down from its Dead Poets Society pedestal and is being reinvented as a viable force that speaks to a new generation. It is highly significant that the first MTV Lollapalooza tour included poetry (and openly homoerotic poetry at that) and that the New York Poetry Slam has been won by at least one unapologetically gay poet. As usual, the lesbian/bi/gay community has moved forward ahead of the times, taking to the Internet, for example, with an alacrity that gives us a disproportionate presence there and on its poetry Web sites.

While there is some satisfying kernel of truth to the hyperbole that the history of American poetry is identical to the history of queer poetry, so many outstanding poets from Walt Whitman to Allen Ginsberg having been homosexual, it is also true that many poets who share our sexuality refuse the appellation and will not consent to appear in the context of our poetry. Disappointingly, some high-profile poets declined to appear in this book, and their refusal shows there is still a sense of stigma attached to identifying oneself as a member of a sexual minority. Most of these reluctant writers are, let's say, of the pre-Stonewall generation, although others, members of racial and ethnic "minority" communities, expressed the concern that a public gay, lesbian, or even bisexual profile would undercut their work in those communities of color. There is much to be done in the new century.

Fortunately, younger poets are creating a far more open field, both for sexuality and for the literature of sexual minority, a field of unity and integration rather than exclusion and separation. There can be little doubt that the relative openness of the world of queer poetry is having an impact on the world of poetry at large.

Significantly, poetry, as the most personal of literary genres, has always appealed to our community — many of us having grown up in secrecy and isolation — and our poetry has long had a committed audience. Richard Labonte, general manager of the A Different Light bookstores, likes to tell this story: When he asks new employees their best guess about the dollar volume of poetry sales, the uneducated estimate is invariably lower than the actual sales figure by a factor of ten. While it is difficult to remember the last poetry title that appeared on the best seller list of The New York Times, poetry is frequently included on such lists in lesbian and gay newspapers.

The world of queer poetry is not, at century's end, looking backward. It is looking forward, its antecedents internalized more often than cited. The reading rooms of cities with large gay populations are no longer entangled in a cobwebby sense of history or duty. Poetry is becoming less like work and more like pleasure. Readings are more than likely to be high-energy affairs, good-humored and heartfelt. This is a community of readers that knows and likes poetry. The readings, which tend to be emotionally interactive as well as extremely lively, set a tone of conversation between poet and audience — a conversation that proceeds form the written word to the spoken word and then back into the written word, as it affects the writing of others. Readings have become community-building affairs, occasions for strengthening identity and community through literature.

The slam sessions at the annual OutWrite conference, a national confab of queer writers and their readers, hold scores of listeners in their sway, even though they last late into the night.

Across the culture, poetry is more available, more present, more "normal." Enrollment in college poetry classes is increasing, and some of our best poets have even developed followings. In New York City, the Poetry in the Motion program of postering subway cars with extracts from poetry past and present has been surprisingly successful in increasing the awareness of poetry. Poetry has shown up on TV's Late Night at the Apollo, too, making Amateur Night winners out of Jessica Care Moore and a Chicago poet who calls himself "The Boogie Man." Even Nike took up the cause, making bus stop posters out of street/slam poets like "Moms de Schemer" (a regular at the historic Nuyorican Poets Cafe, which was cofounded, unsurprisingly, by a gay poet.)

This is not to suggest that LGBT poetry at the turn of the century speaks in one voice, in one style, or even with one notion of generations. Since 1988, the broadening, more inclusive community has become one of the most diverse groups on earth, and the poetry being written by its members is staggering in its variety as well as its energy. This new queer poetry (or perhaps "postqueer" describes it more accurately) is democratic in the best sense, even though individuals may be as elitist about "private languages" as any before us. Many of the writers now emerging came of age long after the Stonewall riots reorganized the social landscape homosexuality inhabits. These young women and men are maturing in a world in which the unambiguous statement of equality has already been made. Their writing lives have had that context from the beginning.

Many of these younger people (and some of their not-so-young colleagues) are drawing on a whole new set of antecedents for their work. Movies, videos, television, and music have all found their way into poetry, in subject matter, rhythm, and form. This is a poetry with one foot at least in city streets, and lingual experiment abounds, from exercises in Spanglish to poems expressed in hip-hop vernacular. But not all young poets write like rap singers, and it was among the great surprises of the research for this book to find how many young writers are enamored of established forms and a sense of decorum that the Beats were trying to subvert.

In "Tradition and the Individual Talent" (from The Sacred Wood, 1920), T. S. Eliot put forth the altogether radical and thereafter normative notion that every new work of art recontextualizes every previous work of art. In other words, history works in two directions, forward and back. Virginia Woolf's Mrs. Dalloway, for example, is forever changed by the 1999 Pulitzer Prize-winning novel The Hours by Michael Cunningham (a gay man), whose book is inspired by and in a way recapitulates Mrs. Dalloway. The writing of today's prominent and emerging queer poets redefines not only the realm of "gay poetry" but that of all poetry (and consequently, of course, of all art, all society.)

The forms of this end-of-century expression range from the most classic to those that are related more to the spoken voice and dramatic monologue than to musical (or mathematical) scansion. Although some of the poets here are self-taught and emerge from oral traditions, many have impressive academic credentials, teach at some of the country's most prestigious universities, and refer often to the world of poetry an dart that has gone before.

As to the content of LGBT poetry today, it is nearly impossible to generalize, but there are common themes. Childhood and loneliness occur frequently, particularly in settings of repressive or abusive birth families, as does the establishment of families of choice. Love, as with any group of poets, is important, and the forging of primary relationships. Impossible and even imaginary loves crop up in a number of the poems in The World in Us. Loss and grief are also major themes, particularly in works related to AIDS and breast cancer, two killers that have devastated not only the wider population but our ranks of poets.

Politics occur regularly, too, both insider and outsider considerations of ordering the world. Ethnicity itself is a theme in much of this poetry, particularly as it relates to multiple generations of ethnicity; frequently the issues of race and sexuality come together in fresh and surprising ways.

Many of the poets here are adept at traditional forms; some are overtly experimental; some draw on prose and in particular the dramatic monologue as a poetic idiom. Some speak in gently introspective voices; others are more outwardly ironic, worldly, troubled. Personal histories that seem emblematic of the clan recur, as do poems of shared cultural icons. Some of these poets write, in part, of exclusion even inside the community.

Sex, sexual identity, and sexual expression are frequently dealt with directly as subject matter, but they also serve as metaphors for "broader" issues. In fact, it has been said that the single most important contribution of queer writing has been the liberation of the American libido, the celebration of pleasure (separate from procreation), the establishment of new patterns of sexual expression. It was writer/historian Joan Nestle, a prominent member of our clan, who remarked that, as a group, we gay and lesbian people are responsible for having written desire into history.

Making an anthology is daunting — partly because there is so much excellent work, but also because so many decisions depend on so many variables. It was clear from the beginning of the project that we wanted to include a larger sample of each poet's work than is traditional in poetry anthologies, where one or two short poems stand in for each poet's career. This meant selecting fewer poets, which was agonizing. But this book is not intended as an overview or a broad sampling of the field, but as a long, curated poetry reading in book form.

Since this is a book about the present and future of queer poetry, its thrust and instinct are intentionally nonhistorical. There are enough books that look backward at the accomplishment off this and other expired centuries. All the poets in The World in Us are living. This was a more difficult decision than it might seem, since premature death has been particularly cruel to some of the brightest and best of our poets of the last decade, and even more particularly to women and men of color.

All the poets live in the United States. Certainly, the world is smaller than ever before, the queer poetry community is more and more international, and great work is being written all over the globe and in many languages. But the field is far too vast to cover it all — even to find it all. We don't wish to imply that queer poetry and queer American poetry are synonymous, but lines have to be drawn somewhere and the border of our begged, borrowed, and stolen country seemed huge enough given the diversity of our population (even though out once vaunted pluralism is increasingly maligned and underappreciated).

All the poets whose work appears here are actively writing poetry. We have chosen not to include people who, for whatever reason, are no longer writing poetry, regardless of how much or how well they have written in the past. Some writers who have been known for their poems in the past declined to be included because they are no longer or not now writing poetry. Some may take to writing poetry again, but we have confined ourselves to writers who are actively engaged in the queer poetry community. Additionally, the forty-six poets whose work follows are all, in some sense, at midcareer.

Now, "midcareer" is a subjective notion. Some of our tribe's spirit mothers and fairy godfathers may still be considered "midcareer," because they are still actively writing, but we have focused on poets who, we suspect, will write their best work in the twenty-first century. This does not mean they are all inexperienced. Most have published books (some, many books), won prestigious grants, prizes, fellowships, residencies. The range of age is roughly midtwenties to mid-fifties. In other words, generally speaking, it's a post-World War II crowd — in some cases, post-Vietnam (if generations are to be marked by violent global conflicts). We assume a bit of prescience here: We assume they will become (or at least have the potential to become) the next century's May Sarton and Langston Hughes, Audre Lorde and W.H. Auden. In some cases, the future of our selected poets is tied inextricably to the future of medicine, as some live with HIV and other physical conditions that may bring an end to their lives before all their writing is done.

We have chosen poets for a variety of reasons: because their work has justifiably captured widespread attention; because the shape or content of their poems sparks the imagination of others; because they are dynamic, inspirational teachers or editors; because individually they offer a missing piece of the social puzzle and together they represent the larger writing world and the large community world(s) they inhabit. Always, the bottom line was excellence. Still, there is not enough room for everyone. For that we would need another book this size, a set or series of books.

No one who edits an anthology can pretend to be free from biases, and we admit we have them. It turned out, for example, that we both have a decided appreciation for (or tolerance of) longer poems than are usually found in anthologies. We both enjoy being moved by poetry, although we acknowledge that "moving" is not the only justifiable or meritorious purpose of poetry.

We know, of course, that there are "schools" of poetry — or rather, to oversimplify, there is "school poetry" and there is "nonschool poetry." Most dichotomies, like that of "gay" and "straight," are inherently false, but for most of this century, criticism has contended with one notion of poetry that is described by words like Apollonian and academic and well-wrought and hermetic (usually exemplified by T.S. Eliot and other erudite white men of privileged class) and another described by words like Dionysian and lyrical and confessional and exuberant (the kind of poetry written by Walt Whitman and by most of the non-white, nonmale, nonheterosexual poets of the twentieth century.)

Like our contemporaries, we are of the post-Beat generation, more Whitmanesque than Eliotarian by persuasion. Like many of the poets we have included, we have a pronounced affinity for pop culture and its expressive forms. This book, you will fink contains more poems about rock musicians and movie stars than about Greek mythology. And the poets are, for the most part, candid not only about their sexual orientation but about their specific sexual agendas and activities. On the other hand, you would never know from reading some of the poems whether the poet was gay or straight, woman or man.

What generalization can be made, we think, is that the poetry being written now by the queer community is active and powerful. It is frequently, although not always, "positive." Rather than simply affirming our legitimacy, it often dares us to improve as individuals and as a community. The poetry here does not embrace isolationism or ghettoization, but attempts to engage readers of all kinds, to grab hold and shake them with the force of the poems. This is poetry written as if the lives of the poets depended on it, and in many ways, they do.

The poets of The World in Us are shaping their lives and the lives of others with words; their collective modus operandi is to affect everyone who comes into contact with them — perhaps effecting changes in consciousness or behavior along the way — as if each poem were a new sun that casts for each reader an unfamiliar shadow. The strategies are diverse: the poems challenge and shock, they explain and assault, they entertain and amuse. It is strong work from a group of strong individuals. It is work that is not shy about its medium or its content. It is poetry that makes visible the world in us. It is poetry of the necessary word.

Michael

Lassell

Elena Georgiou

New York City

Copyright © 2000

Michael Lassell and Elena Georgiou.

Back

to the Stonewall Inn

Back

to the Stonewall Inn