|

|

||||||||

| Excerpts: | ||||||||

|

Letter From the Editor

![]()

"Sittings and Stirrings"

"Sittings and Stirrings"

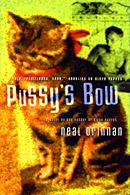

From Pussy's Bow

"Honey, we’re home!" Doc and Dix burst through the front door. Bustling into the kitchen, they found the slender figure of their housemate bent over some legal documents.

"What are you doing?" asked Doc.

"Oh, just forging my grandmother’s signature." Dung straightened his cherished privacy and calm shattered.

"She’s dead, isn’t she?"

"Yes, but they don’t have to know that."

"I’d better keep my prescription pad under lock and key then."

Dixon laughed. "Giving you a prescription pad’s like giving a junkie an AMEX."

Doc flushed slightly. "Well I’m off to the gym as soon as I’ve cleaned up and changed."

Dix quirked an eyebrow at Dung. "Don’t forget to wash your hands," he called as Doc vanished into his room.

As soon as Doc had gone, Dix shed his gear to pose for Dung, their artist-in-residence. Dung slept and worked in Juliette’s third bedroom and had done so for some months. His room was at the very back of the house and was blessed with a whole wall of latticed French windows looking onto the small, immaculately kept garden. It was large, long and made for a perfect studio. Dung never minded sleeping with paint or turpentine fumes–he’d been weaned on Agent Orange.

His last exhibition, Giet su khoan dung (Slaying Tolerance), had gained him national notoriety, a major art prize and $75,000 in painting sales. The National Gallery in Canberra now housed one of his largest works–a purchase more bigoted forces in the country saw as "a public purse apology to recently vilified ethnic groups."

Doc had been one of the buyers at this exhibition and while both Dix and Dung agreed their landlord was essentially a philistine, they both loved his house and preferred to have their party drugs injected by a qualified medical professional. The painting he bought, Viec lam dem tu do (Work Makes Free), looked truly remarkable over Juliette’s huge Deco fireplace.

Dung’s paintings were a strange combination of styles, partly recalling traditional Orientalism and partly inspired by Russian communist propaganda from the thirties. Work Makes Free depicted Melbourne’s wealthiest Vietnamese restaurant owner in one of his chic and modern Victoria Street establishments. He was holding up his obese, rosy-cheeked son while, in the background, stylishly dressed Vietnamese couples sipped wine and nibble goi cuon. Behind them, paintings on the walls depicted Vietnamese war atrocities: people being suffocated with plastic bags, babies on the ends of swords, the usual sort of thing. Some of Dung’s paintings had made him less than popular amongst the Vietnamese community. His family, well, they were a-whole-nother story.

Dixon’s painting seemed to require an inordinate number of sittings. As he lay there, Dix looked over at Dung’s next major work. A particularly Gothic piece, Murmurs of Genocide seemed to combine every horror of prejudice known to man from the Spanish Inquisition through to Pauline Hanson, and included a distressed looking Hassidic Jew about to throw himself from Juliette’s turret. Dix didn’t dare mention to Dung that it was highly unlikely Juliette’s original owner was Hassidic.

"What do you think?" Dung noticed the perplexed scowl on his model’s face.

"It’s too hysterical a response to contemporary Australian racism to have any intrinsic artistic merit. Where’s your usual subtlety, Dung?" Dix’s voice was laden with sarcasm.

"You stick to your gardens, literary references and Toorak matrons–I’ll deal with the painting of life as I see it, alright?"

Pauline Hanson was what Dix couldn’t stand. "The mere depiction of that woman parochialises and lowers the tone of the work." She doesn’t deserve a place amongst the likes of Pol Pot, Stalin or Hitler–you flatter the woman more than she deserves by counting her amongst them."

"Even Hitler had to start somewhere and the German people were probably more shrewd than the Queensland rednecks," replied Dung, unswayed by Dix’s counsel.

"She’s so god-awful. Who’s going to mount her on the wall?"

"Who’s going to mount her anywhere?" said Dung with an evil grin.

Dixon looked across the room to that cruel mistress, the mirror. Age had altered the set of his face. "They say your nose keeps growing until you die–that’s a depressing thought."

"They say your nails and hair keep growing even after you die," answered Dung.

"Yes, well, ‘they’ have a lot to answer for."

Dung laughed at his own vanity and narcissism. He wondered if homosexuals were merely creatures of the spring. "Perishable amusements–the castrati of a thankless contemporary world," his friend Soren had once claimed. Dix comforted himself with the thought that most homos aged better than their straight male contemporaries and amused themselves far longer. Still, he was pleased his immortalisation was taking place now, before the rot could set in any further. He shuddered at the memory of fifty-year-old queens with sun-seared lizard skins lolling about in G-strings on Melbourne’s summer beaches.

Dung paused from his painting, remembering different things in association with aging. He thought about Reg, the hideous old letch he’d lived with for a year when he was eighteen. He remembered how Reg had showered him with jewelry, aftershave, and Lloyd Webber shows, only to abuse him whenever Dung wouldn’t do as she was told. "Oh, so she’s not happy being Miss Saigon, now she wants to be the fuckin’ queen of the Orient. All pearls and diamonds, but no put-out."

When Dung had tried to go home to the commission house where his mother lived in Preston, things were no better. She’d driven him into the arms of that slimy creep with her histrionics. He shuddered, remembering how she would chase after him, grabbing at the jewelry he wore, shouting abuse in a concoction of English and Vietnamese.

Dung sighed and came back to the present, his hands smearing splashes of deep red and fleshy pink on the canvas. He never allowed his reveries to engage him for long. What did the past matter?

Dix watched as Dung focused intently on his work. His hair, a short, wavy bob, refused to stay behind his ear, and he had a cute way of flicking it back so as not to get paint in it. Dung’s body, too, was in great shape. It didn’t have that dogged look that Doc’s had. Muscles rippling sinuously beneath the tattoo of a Celtic cross-an absurd design for one so obviously Asian.

Still, its owner was exquisite, he conceded. Nearly thirty, successful and wearing all the correct hallmarks of the ruling gay tribe, Dung was quick, angry and political. All the same, Dix understood that Dung’s artistic earnestness masked a healthy appetite for the ways of the flesh and a real hunger for love.

Dung’s eyes were eager to recognize his housemate’s desirous glances. With his success and the gradual Anglo acceptance of Asian beauty, he’d grown increasingly accustomed to such looks. He felt his body respond and silently cursed his involuntary self-betrayal.

Dix noticed the slight bulge in the front of Dung’s white trousers. Bless him, he thought, and allowed his own cock to increase in size just the teensiest bit.

Dung smiled, acknowledging the compliment, but realized nothing would come of it today.

For his part, Dix knew his own naked asset was the real reason Dung was so keen to paint him. Why, he thought, did every gay boy go weak at the knees when they saw the size of his schlong? The legendary appendage had saved Dix from having to make too much of an effort in other ways, socially or sexually. Doc though he should get a mould made. "We could market it as a dildo, like Jeff Stryker, only yours could be called Dixon Brearly–Really. Whadaya say, Dix, shall we take a mould?"

Copyright © 2000 Neal Drinnan.

Back

to the Stonewall Inn

Back

to the Stonewall Inn