| Home | Tours/Lectures | Books | Maps | Posters | Pictures | Contact |

TABLE OF CONTENTS Before You Start Introduction Tour I: From Dene to Green Tour II: Overlook Rock Tour III: Umpire Rock Tour IV: Belvedere Lake Tour V: Woodland and Waterside Glossary |

TOUR III: UMPIRE ROCK

If you've just come from Overlook Rock, with its neatly color-coded intrusions, you may be thinking that there's not much to this geology business after all. Umpire Rock, with its complexities and contradictions, is a good corrective.

Come into the park on the footpath to the west of the Seventh Avenue entrance, walk north, cross at the traffic light and continue past the beginning of the bridle path.

|

| Glacial grooves on the northwest slope of Umpire Rock. |

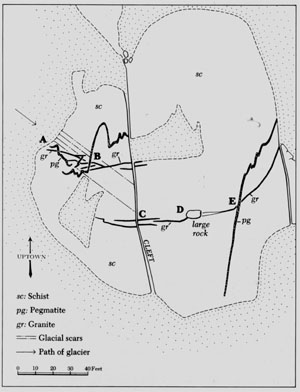

At lamp post #6125, turn northeast and walk up onto Umpire Rock. Follow the lines of foliation to a grassy rectangle whose northern corner leads to a shallow valley in the rock. The surface of the slope is scored with five glacial grooves that look as if a giant hand had clutched the rock while it was still plastic.

Walk to the bottom of the slope and turn to face it. Three feet from its base, you can locate the start of a fairly straight layer of granite, 2 to 3 inches wide (A). Just below it, a band of pegmatite zigzags up the slope, conforming to the intensely folded layers of schist. Where the two layers meet, the pegmatite appears to cut across the granite. The juncture is rather blurred yet the presence of large pegmatitic grains at the crossing seems to present a puzzling reversal of previously observed rules.

|

| Pattern of intrusions on Umpire Rock. |

According to expectation, a large-grained, strongly folded intrusion should be an early one which entered a body of heated rock during deformation and cooled slowly within the enclosing mass. By the same token, a straight dike of fine-grained granite is presumed to be a late intrusion, injected into a fracture in nearly cool rock. Yet here the pegmatite seems to intersect the granite as if it had been forced into the host rock after the granite had been emplaced.

Let's look for more such junctures to see if the apparent anomaly is repeated elsewhere on the outcrop. The first band of granite turns into diminishing ribbons and vanishes to the east, while the pegmatite winds over the slope and joins a much broader band coming in from the northwest. Thirty feet from the base of the outcrop, the pegmatite crosses a jagged groove that runs down the center of the rocky valley. Here again, and this time more clearly, the pegmatite cuts across two slender bands of granite (B). The granite is strongly folded while the pegmatite, enclosed between layers of schist, straightens out and heads across the slope to the north.

Follow the granite layers in a southeasterly direction until they disappear at the edge of a cleft. Walk south along the cleft for thirty feet and cross it where some surviving blocks of schist almost close the gap. On the far side, two narrow lines of granite (C) run almost due east. If you look closely, you will see that the central part of the granite contains some large pegmatitic grains, evidence of a complex, repeated injection with distinct variations in the rate of cooling.

|

| The northern face of Umpire Rock. |

The more northerly of the two granite dikes runs east and ends on the face of a small cliff (D). Contact between granite and schist must be weak, as the mass has fractured along one or the other margin of the dike. Some of the layer of granite remains attached to the lower part of the cliff face. Other traces of granite are visible near the bottom of the nearby rock which split off from the main body along the contact zone. The broken slab has been overturned and shifted to its present position, probably by human agency. If your imagination is powerful enough to flip the rock over, you will see that the slices of granite adhering to it would dovetail with those on the cliff face.

Walk around the rock and follow the grassy gully that marks the continuation of the easily eroded granite dike. The granite surfaces again eighteen feet to the east of the loose rock and turns towards the north in a series of folds and broken lines. Once again it is cut across by a 4 inch layer of pegmatite (E). This time there is no blurring: the intersection is sharp and the sequence of injection unarguable.

The puzzle is intensified when you remember that granite and granite pegmatite are alike in composition and differ only in grain size which is largely governed by the rate of cooling. How could a fine-grained granite, the product of rapid cooling, have preceded a slow-cooled pegmatite?

Some geologists believe that rocks in the area may have undergone more than one period of metamorphism. If this is so, the granite may have been injected towards the end of an early stage when the deeply buried mass had partially cooled. When the rock heated up again, both it and the granite dike may have become ductile enough to fold under pressure yet not hot enough to forfeit their distinctive grain formation. Suppose a second wave of molten material had entered the mass at this stage, following in large part the layering of the schist but cutting across the granite. Because the surrounding rock mass was hot, the intrusion would have cooled slowly and hardened to pegmatite. This reconstruction, while speculative, seems to reconcile the sequence of injection at Umpire Rock with observations made on earlier tours.

Before you leave Umpire Rock, retrace your steps and walk around the north side (provided the ground isn't too muddy) to admire the intricate sculptural folds that ornament the face of the cliff.