|

|

||||||||||||

|

The Author's Intro |

||||||||||||

| Excerpts: | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Illustrations: | ||||||||||||

|

Gay/Lesbian/Feminist Bookstores Around the Country

The Mostly Unfabulous Homepage of Ethan Green

![]()

The Author's Introduction

The Author's Introduction

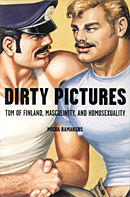

Micha Ramakers on Tom of Finland and the making of Dirty Pictures

Tom of Finland used to say that when he first started out,

he would know a picture worked if he became too aroused to complete it.

His monumental output of well over thirty-five hundred drawings spanning

four decades suggests that if he continued to use that (fairly foolproof)

method, over the years he developed sufficient self-control to go on drawing

despite his erections. In doing so, Tom of Finland became the best-known

and most widely appreciated produced of gay erotica of the second half

of the twentieth century. He provided immeasurable pleasure to several

generations of gay men and, furthermore, offered what had seemed unattainable

for many of them: tools for an affirmative identity. For these reasons

alone – but there are many more – his work deserves to be the

subject of critical attention. But that has hardly been the case, and

this dearth of critical writing is not surprising. On the one hand, academic

interest in porn is fairly new and has focused on an ideological critique

of its negative consequences (porn as the perfidious promoter of oppression,

violence and rape), although more positive attitudes have become increasingly

prevalent in recent years. On the other hand, for the great majority of

Tom consumers, it’s the drawings that matter and not theoretical

insights. The need for deeper analysis is, in this context, usually fairly

limited.

Tom of Finland started drawing his fantasies in Finland in the mid-forties. Tom’s work consists almost exclusively of drawings executed in an illustrative style. From the outset, the essential characteristics of his work were firmly established. Tom invariably employed a combination of highly realistic elements, such as clothing and surroundings, and of exaggeration to the point of caricature of certain body parts – for instance, genitals and torsos. A sensual handling of matter and a high degree of polish aimed at leading his viewers" attention past technique to the action depicted, stimulating not the intellect but the instincts. This visual "deception" is central to most pornography (and to other images that directly appeal to the view’s instincts, such as political propaganda or advertisements.)

Tom of Finland truly perfected this technique, which is one explanation for his lasting success. His work remained highly appreciated throughout a career spanning more than forty years, and its popularity has only increased since his death in 1991. In the early days this was because of its erotic power, and his work only reached a small group of "insiders." Later his work was distributed on a larger scale, first through porn magazines catering to an ever – expanding gay market. Because of its superb technical quality, his work became highly regarded in an increasingly assertive gay subculture. From being "only" porn, it became a collectible cultural article. Artists such as Andy Warhol, David Hockney, and Robert Mapplethorpe made no secret of their admiration, and the latter collected and promoted the Finnish pornographer’s work. Traces of Tom’s influence could increasingly be found in other artists" work. Tom, meanwhile, turned out to be fairly immune to reverse contemporary artistic influences.

As with his style, Tom’s themes were hardly subject to fundamental change. Neither the liberalization of legislation governing pornography nor artistic recognition had a decisive influence on his work’s basic premise. The relation between sexual pleasure and power remained its central theme throughout. His oeuvre is characterized above all by a high degree of consistency. Evolutions in style and subject matter should be seen as an expansion of his register rather than as radical changes. His almost obsessive adherence to one style and theme – and over time those two elements became inextricably connected – formed a key element in Tom’s creation of the most effective propaganda for a gay utopia produced to date.

For many gay men, Tom of Finland’s work has played an important role in the creation of an identity. This phenomenon was not limited to the United States, but has played a significant role throughout, and sometimes even beyond, the Western world. This was, among other cultural and social factors, a consequence of the fact that homophobia’s mechanisms were – and remain – quite similar in all these societies. In the fifties and sixties, Tom’s work offered a sharply contrasting image of homosexuality to the one that was considered – even by most gay men – universally valid. He invited a (pretty butch) fairy-tale gay universe in which masculinity was held up as the highest ideal. Somewhat paradoxically, such a supposedly "gay world" came to be populated with characters whose sexual identity was often more ambiguous than some cared for. Initially, such ambiguity reflected the state of mind of many homosexual men at midcentury, who maintained that this "true" masculinity could only be found in others (or even Others.) Although the rough trade of bikers, soldiers, hustlers, and sailors who appear in great numbers in Tom’s pictures needed gay society to establish their identity, this was distinct from gay identity and ultimately lay outside rather than inside its borders.

The "stonewall revolution" of 1969 may be considered a turning point in that respect. Although it would be an oversimplification to ascribe to it all the radical changes that occurred in gay culture from the late sixties until the early eighties, from that moment on ever greater numbers of gay men came to identify themselves first and foremost as men. Gay men, sure, but men. Inversely, it can plausibly be argued that men who would not previously have viewed themselves as gay (never mind the objects of their lust) were increasingly prepared to label themselves as such.

This evolution is clearly signaled in Tom’s work of this period. From an unreachable utopia, it turned into a world that was not only desirable, but recognizable and even "doable" for many gay men. A great appropriation was begun of the symbols of hegemonic masculinity in its most corporeal expressions. Gay men creatively and extensively "perverted" masculinity and all its idiosyncrasies to elaborate a hybrid new identity. Tom’s work served these men as a highly outspoken and quasi-omnipresent primer for their project.

Soon it seemed as though this new reality was overtaking Tom of Finland’s images. The things urban gay men could do to themselves often went way beyond any aspect of this body of work. Thus conceptions of Tom’s work changed. What had once appeared to be the ultimate dream vision was rapidly turning into a folkloric image of a sexuality that seemed to have broken through the work’s borders. Tom’s work was well under way to become retroporn, together with the pictures of young bodybuilders that had graced the pages of Physique Pictorial, in which Tom had made his debut in the late fifties. In the early eighties, however, this evolution was disturbed by the spread of HIV and AIDS. Together with the gay male sexuality of the seventies, Tom of Finland’s work, it seemed, would be definitely discredited. That did not happen.

Indeed, at the end of the eighties his work even became acceptable to the mainstream art world, thus precipitating the unlikely apotheosis of an unlikely project. For a long time work such as Tom of Finland’s was unacceptable within the art world. One explanation undoubtedly lies in its explicit sexual nature. Also – and perhaps to the same degree – the uncompromisingly "smooth" technique with which the work was executed played an important part in its rejection as not having anything to do with "Art." Only from the eighties, when the dogmas of artistic avant-gardism were challenged, was such work (again) offered a serious place within the art world. The changes in thinking about art led to a reappraisal of some older painters who had stuck to figuration throughout the postwar reign of abstraction. Tom of Finland, too, from that time onward enjoyed some recognition as a bona fide visual artist. Furthermore, his themes came to be experienced as less problematic than in earlier decades, partly under the influence of the sexual revolution and the general entry of explicit homoerotic images into art’s mainstream.

This new recognition, then, was also connected with a redefinition of the very notion of art, an evolution that allowed a strong interest in popular images (movies, comics, non-Western art, graffiti, virtual art, porn, and so on) to blossom within the art world, and a fortiori within the art sciences (as art history is now called). Today art historians may contribute to the analysis of such phenomena without automatically sacrificing any and all legitimacy or without uncalled-for appropriation of such popular cultural expressions for the canon of high art. It has, though, turned out to be difficult – and, as far as I am concerned, not desirable – to disconnect the production of what has traditionally been cataloged as art from these popular forms. Nevertheless, it would not be very productive to discuss Tom’s work from a purely art historical point of view or to use only art historical methods. In writing this book, I have used a combination of methods, both from the art sciences and from cultural studies, gratefully and extensively drawing on theoretical insights about gender, sexuality, and race. I want to stress, though, that it was never my intention to write a theoretical treatise. I have used the tools offered by different branches of the humanities to interpret homoerotic images. However, this is not a book about system theory, but about gay porn.

A further word of warning, perhaps: this is not a biography either, although Tom’s life is discussed where it may clarify certain aspects of his work. What has concerned me most as I was writing this book is how Tom of Finland’s work functions, why it has the impact it does on those who look at it, and to what extent it is connected to, or may even lie at the basis of, social and historical evolutions within gay culture. I have focused my analysis on the ideologies that rule Tom of Finland’s work – though not, as is so often the case, with a view to putting the work at the service of ideology, but rather aiming for the opposite. I hope the reader will find in this book a contribution to understanding the legacy offered by gay porn and, even more, a source of pleasure.

Copyright © 2000

Micha Ramakers.

Back

to the Stonewall Inn

Back

to the Stonewall Inn