|

|

||||||||||||

| Excerpts: | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Illustrations: | ||||||||||||

|

![]()

The

Emperor's Old Clothes?

The

Emperor's Old Clothes?

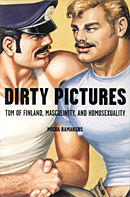

From Dirty Pictures by Micha Ramakers

In Ilppo Pohjola’s documentary Daddy and the Muscle Academy, a number of working-class gay men discuss the importance Tom’s images have had for them in forging a masculine gay identity. As one man said, "His drawings are basically blue-collar men, and seeing two blue-collar men enjoying each other made [being gay] more acceptable to me, and up to that point, coming from a very blue-collar background, I had all very negative associations with it.. When I finally did come out, it made me feel more comfortable with who I [the interviewee hesitates]… more comfortable with the fact that I am gay and that I like other men."

As mentioned in previous chapters, in working-class culture, homosexuality was equated with being a fairy, a woman in a man’s body, to a larger extent and for a longer period of time than in middle-class milieus. In the postwar period, such stereotypes were I part reinforced and in part replaced by antigay rhetoric, which stressed the perversity of homosexuality. As Pierre Bourdieu has argued, the masculine, muscular body played an important role in working-class ideology as "the popular valorization of physical strength as a fundamental aspect of virility and of everything that produces and supports it." For working-class gay men, then, images such as Tom of Finland’s (and those produced by physique photographers) may have had a very different meaning than for middle-class gay men. Rather than offering a spectacle of the "other" to whom middle-class gay men so often felt attracted (ample literary and other evidence exists of this phenomenon), for blue-collar men such images offered a means of direct identification as both gay and masculine.

In mid-century Finland, which had an important timber industry, the lumberjack was on of the most unequivocal and readily available hypermasculine types, and, according to many interviews, Tom was attracted to such men from his early boyhood. In Figure 37 (p. 129), a muscular, blond young man stands in the foreground, stripped to the waist. He is wearing tight jeans and waders, and in his right hand he holds a long stick topped by a hook. His left thumb is hooked behind the waistband of his jeans. In the background, by a riverbank, a tree trunk is being lugged by a similar figure. This is the type with whom in 1957, Tom would make his successful U.S. debut in the muscle magazine Physique Pictorial (Figure 22, p. 82).In the drawing chosen for that spring issue’s cover, two boys, similar to those in the drawing mentioned above, are standing on tree trunks and floating down a river. The boy in the foreground has a knife in a holster that hangs from his waist.

Lumberjacks appear frequently in Tom’s early work. Although none of the published early drawings featuring lumberjacks contain any sexual activity, the Tom of Finland Foundation has more than a dozen such pictures that are sexually explicit in its archives. The earliest of these pornographic drawings date back to 1945. None of those images were produced for publication, but Tom drew them for himself and as private commissions. The lumberjack was on of the earliest blue-collar icons to appear in Tom’s work. Tom’s interviewers and his biographers have largely ignored class issues. As were so many middle-class gay men of the era, however, Laaksonen was consistently attracted to images of working-class masculinity, images that initially focused mainly on the "natural" bodies such men possessed, but that would rapidly extend to a fetishization of working-class dress codes (objects that could be construed as middle class were by and large removed from his work at an early stage). Lumberjacks continued, be it to a lesser extent than in the first years, to play a part in Tom’s work, as is illustrated by a 1966 drawing (Figure 3, p. 34). It would not be until 1973, however, when he produced the comic strip Loggers, that Tom would assign lead roles to lumberjacks in a sexual scenario specifically destined for publication.

Cowboys made their first appearance in Tom’s work in the early sixties, most likely at the behest of American clients. In North American culture, the cowboy plays an important role as a bearer of mythical masculinity. He was the pioneer who opened up the Wild West of the "new" continent. He lived with his buddies (and the cows) in a closed community of men outside the social mainstream and symbolizes virile camaraderie in a hostile natural environment. The cowboy is prominent in both the dominant U.S. culture and in the U..S. gay subculture as an "indigenous" ideal of masculinity, a theme played upon by a large number of westerns and satirized by Andy Warhol in his 1967 film Lonesome Cowboys. Cowboys were a staple of fifties and sixties physique magazine; Tom on Finland’s predecessor at Physique Pictorial, George Quantaince, had a predilection for the type. Tom thus continued a well-established tradition, although his cowboys were "today’s cowboys… not a historical representation. There’s a clear sense that they’re actually related to contemporary [people] subverting traditional concepts of power in Western society." A drawing from 1960 [Figure 38, p. 1231) shows a cowboy wearing his typical hats, boots and spurs, and a gun belt. He is walking away, offering a cheerful salute, from two men he has tied together with his lasso. This is a theme that, to a limited extent, would continue to return, as a drawing produced in 1979 demonstrates (Figure 39, p. 132). In it the cowboy has used his lasso, not to catch the customary cow, but a naked "slave" – once again a mixture of two different codes that allows for a more unequivocally gay reading than the previous image. By then, however, the cowboy image had taken on distinctly gay overtones, sufficiently even to be played upon in a mainstream Hollywood movie, Midnight Cowboy (1969), where Ratso (Dustin Hoffman) provides rookie hustler Joe Buck (Jon Voight), who goes around in full cowboy gear, with an unwelcome insight about this outfit: "If you wanna know the truth, that stuff is strictly for faggots! That’s faggot stuff."

Construction workers entered Tom’s work relatively late. A drawing date 1978 (Figure 61, p. 173) is the earliest example known to me. In this drawing, Tom placed his well-known physical types in a new setting – but one that maintains the hypermasculine atmosphere typical of his work. Their arrival was, once again, directly connected with the changing nature of the subculture and the artist’s growing familiarity with everyday gay life in the United States, where the "construction worker" had meanwhile become a fixed type in gay culture. As Tom said in the early eighties, "the new hero is the builder. Guys in overalls and hard hats. I’m glad my men are such obvious gay men. They’re not queer, not kinky, but gay. In the past, homosexual men have always been typed as weak and characterless. That image is changing now thanks to those macho fashions." A series of drawings produced in 1988 that includes Figures 18 ()[. 75) and 40 (p. 133) illustrates how Tom continued to explore the lasting erotic potential of the building site and the construction worker even after the clone had ceased to be a current gay type.

Copyright © 2000

Micha Ramakers.

Back

to the Stonewall Inn

Back

to the Stonewall Inn