|

|

||||||||||||

| Excerpts: | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Illustrations: | ||||||||||||

|

![]()

Being Sexed is Hard

Word

Being Sexed is Hard

Word

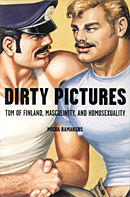

From Dirty Pictures by Micha Ramakers

Between the last third of the nineteenth century and the middle of the twentieth century, a sizable scientific and ideological apparatus was developed that focused on the physical features of the bodies of gay men. This was not exclusively an endeavor of presumable hostile scientists; significant numbers of prominent homosexual men actively participated in this exercise, seeing in the biological origins of homosexuality a means of bringing about social acceptance of their "nature," a project that finds odds echoes in today’s "gay brain" theory. A gay body was thus brought into existence, a body that did not qualify as either properly male or female; it was that of a third sex of so-called urnings. This truly queer body was the carrier of a umber of distinctive, be it sometimes contradictory, features: a slight build, excessive fat deposits, wide hips, soft skin, pubic hair that followed a female pattern, narrow shoulders, a boyish face, an abundant head of hair, an inability to whistle, and "too good" looks. They were, in a word, feminine (but not female) bodies. As that famous authority on all things sexual, Mae "I got seventeen real live fairies on stage!" West, once put it:

I was fighting for Gay Rights before it became fashionable… way back in the twenties, in New York, I got ahold of the police and started explaining to them that gay boys are females in male bodies. That’s Yogi philosophy – take it or leave it… The police were really rough on homosexuals then. I said, now look, fellas, when you’re hitting one of them, just remember you’re hitting a woman. That straightened them out. They stopped beating up the gay boys.

Apart from Mae West’s characteristically overoptimistic estimation of her ability to stop police harassment single-handedly, these remarks illustrate that this amalgamation of gayness with femininity, and the social place and role of the female sex, was widely adhered to throughout the Western world in the first third of the twentieth century. These beliefs were not limited to an elite circle of scientists and social leaders, but also enjoyed credence in popular circles. As the historian George Chauncey has pointed out, the working-class understanding of gay men as members of an intermediary, third sex was based on a conception of sexuality that was very different from today’s and stood "at the center of the cultural system by which male-male sexual relations were interpreted":

The fundamental division of male sexual actors in much of turn-of-the-century working-class thought, then, was not between "heterosexual" and "homosexual" men, but between conventionally masculine males, who were regarded as men, and "homosexual" men, between conventionally masculine males, who were regarded as men, and effeminate males, known as fairies or pansies, who were regarded as virtual women, or, more precisely as members of a "third sex" that combined elements of the male and female. The heterosexual-homosexual binarism that governs our thinking about sexuality today, and that...was already becoming hegemonic in middle-class sexual ideology, did not yet constitute the common sense of working-class sexual ideology.

"Masculine" men who had sex with "fairies" were thus not considered homosexuals – as would be the case today in Western societies – but as men, men who sought to be serviced by "females," whether they were biologically male or female. Having your cock sucked, or fucking another man (in short, sticking to the "active" penetrative role), did not result in a loss of masculinity: these acts were not defined as having any connection with a specific "sexual orientation." Such "active" men definitely did not regard themselves as gay, although they would be thought of, and would most likely considers themselves to be, gay in today’s circumstances. Back then, they were "trade," straight men who were not averse to sex with other men, but who would play only the "male" role. Although, as Chauncey noted, a shift was occurring in middle-class ideology away from identities exclusively based on gender toward sexuality – based social roles, it would be a long time before the seemingly immediate link between homosexuality and femininity would cease to play an important role in the thinking of both gay and straight people alike. When he was young, certainly Touko Laaksonen – as many gay men – was influenced by this conception in finding a gay identity: "For a while… he replaced his neckties with colorful scarves, and his shirts sometimes edged dangerously close to being blouses." It has been tempting to many later gay commentators, who have heavily invested themselves in the masculine redefinition of homosexuality, to see the situation of prewar gay men exclusively in terms of oppression, and the emergence of a masculine gay identity only as a liberation. A commentary in a video on Tom of Finland attest to how far this masculinist conception of gayness is removed from that of the early twentieth century:

As the war came to an end, Tom’s true sexuality began to emerge… In the late 40s at a time when to be homosexual was to be effeminate, and guilt was the tribute extracted from those who dared to rebel against the sexual norms of the era, Tom rejected this concept and began to construct his image of masculinity. Believing that a man could be strong, happy, manly AND homosexual, he began to formulate the prototype that has become the quintessence of gay masculinity the world over.

It is worth keeping in mind in the face of such hyperbolic ideas that early twentieth-century fairies were not pathetic creatures who were merely conforming to an oppressive and externally imposed set of rules. Fairy identities – and related social and subcultural forms of expression – were willingly embraced by many (mainly working-class) gay men and, going by the evidence available, most probably provided them with as much pleasure as today’s masculine identities. The majority of (mainly middle-class) gay men, though, identified neither as "fairies" nor as "normal," but as "queer." such men did not adopt the behavioral styles of either group, although they borrowed from both, but did see themselves as men. Nevertheless, they, too, overwhelmingly understood their sexuality as a feminine desire. Few gay men saw their homosexuality as part of a masculine continuum embodied by icons such as the American poet Walt Whitman. By the 1940s, this gender-based identity was well under way to being (at least partially) replaced by a sexuality-based one. Rather than being a lonely outpost of masculine homosexuality, then, Touko Laaksonen’s move away from femininity in the late forties and early fifties coincided with a general cultural shift away from gender-based identities, which accorded a feminine role to gay men, to sexuality-based identities.

Damn Queers

In his introduction to Retrospective, Tom of Finland wrote, "I started drawing fantasies of free and happy gay men. Soon I began to exaggerate their maleness on purpose to point out that all gays don’t necessarily need to be just "those damn queers‚ that they could be as handsome, strong, and masculine as any other men." Such assertions were experienced by many gay men as liberating, in view of their growing dissatisfaction with the previous models offered for (and by) gay men. This is one of the reasons that Tom’s work successfully touched a raw nerve in so many gay men. A typical reaction was that expressed in James Williams’s extraordinary ode to gay masculinity.:

How fortunate are we who appreciate the strong masculine fantasy imagery brought forth through Tom’s insatiable urge to recreate his world through his art. Keeping in mind the oppressive society from which Tom sprang, what a revolutionary concept was being asserted I his work: that of masculine homosexuality. We can only speculate what life would be if we still were forced to feel that to be gay is somehow not male.

The most significant shift in postwar gay identities in the West has undoubtedly been this great trek toward masculinity. Rather, however, than being seen as an uncovering of the "hidden truth" about gay sexuality, as has been argued by scores of gay theorists, it should be seen within the context of a changing general society, a society that became based less on gender than on sexuality. Masculine gay men, who could (and probably would) previously not have considered themselves gay at all, were led in postwar Western societies to reconcile their gay identity with dominant concepts of masculinity. Gay men who could (and often would) have found a positive identity in being a fairy were not confronted with a culture that no longer viewed them as failed women, but as homosexuals. As once-fixed gender identities were replaced by fixed sexual identities, the development of a masculine gay identity became a necessary project.

In an article on contemporary gay video porn, written in the early nineties, Mark Simpson accused Tom of Finland of being directly responsible in his early work for "set[ting] up virtually all the styles and conceits that are used in gay porn today…His drawings depicted a guilt-free (and gay free) world of spontaneous public sex… What should be the most obviously, unapologetically, explicitly gay images… become something not very gay at all, something that instead goes out of it way to distinguish its men from "those damn queers": a position rather similar to straight male porn." This is very much an early 1990s reading of Tom of Finland’s work. Since Mark Simpson does not say exactly what images he holds responsible for what could be called the Tom of Finland Fallacy, it is difficult to counter his argument in detail. However, Tom of Finland’s early work should be read against the background of the changing conceptions of gender and sexuality. Then a somewhat different picture merges, which casts Tom not as the devious pioneer of a paradoxically nongay gayness, but rather as someone whose work often reflects the general attitudes of the era.

Fairies and Trade

The dominant images of Tom’s men is that of pumped-up bodybuilders. While this is definitely a correct perception, other body types do figure in his early work. A picture from the forties (Figure 13, p. 68) provides a glimpse of a world divided into fairies and trade. A centrally placed biker is being accosted by two young men, who are aiming for his crotch. The biker does not take an active sexual interest in the two others, but is happy for them to "service" him. Whereas the biker is portrayed as utterly manly, the two other men are obvious fairies. Dress codes and sexual acts are the subjects of later chapters, but the body language of the two leaves little to the imagination as to their position in the gender/sex system. Other drawings from the forties and early fifties reflect the respective positions of fairies and trade in much the same way; only by the mid-fifties would fairies disappear from the work – as will be shown further in the text.

During the decade following the fairy’s demise, roughly between 1954 and 1963, trade would be the main social type represented. Tom’s lumberjacks, discussed in greater detail in the following chapter, are exemplary of this type: they are the bearers of a natural, uncomplicated masculinity, their muscular bodies the result of physical labor (and not the gym). These boys were not meant to read "gay" but "masculine," and only that. Several biker drawings from the fifties are vivid illustrations of the way in which trade begot trade in this stage of Tom’s developing world, rather than relying any longer on the services provided by fairies. Both in Figures 14 (p. 70) and 15 (p. 71), two bikers are having sex with each other. In both cases, the partners are equally masculine and equally "nongay" (or vice versa). The masculine redefinition of all partners in gay sex, though, had taken a start. From the mid-sixties onward, gay characters – properly Tom’s Men – started to dominate his work, and the era of trade and fairy would be drawn to a definitive close.

Copyright © 2000

Micha Ramakers.

Back

to the Stonewall Inn

Back

to the Stonewall Inn