|

|

||||||||||||

| Excerpts: | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Illustrations: | ||||||||||||

|

![]()

I

Love a Man in Uniform (I Need an Order)

I

Love a Man in Uniform (I Need an Order)

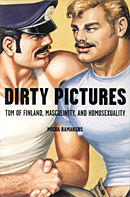

From Dirty Pictures by Micha Ramakers

In addition to the codes of masculinity transmitted through icons of physical labor and rebellion, Tom of Finland made extensive use of an altogether different category of attire: uniforms. His work is overflowing with images of sailors, soldiers, police officers, and prison wardens. Why were these types and their outfits so attractive to gay men? What were the consequences of using such strong signifiers of masculinity in gay porn?

Hello, Sailor

Until the end of the sixties, sailors played a major role in Tom’s work. These men traditionally were the symbol par excellence of a readily available fuck. Sailors were, because of their prolonged stay at sea, not averse to gay sex. Their tight, crisp white or blue uniforms, which emphasized all the "right" physical features, and their masculine demeanor, exerted a strong attraction on many gay men. Large port cities traditionally had "looser morals," and anonymous sexual contact was more readily available. Sailors, indeed, were here today, gone tomorrow, and were therefore free to do whatever they liked.

In twentieth-century homoerotic imagery, sailors occupy a prominent place. Many writers and artists, both in Europe and the United States, have put sailors squarely at the center of their fantasies: one well-known literary example is Jean Genet’s novel Querelle de Brest. In the visual arts, too, this tradition goes back a long way. Both before and after World War II, a number of figurative painters more or less discreetly produced homoerotic images. Without exception, sailors are present in their work. They are invariably meant to be erotic, sometimes in a directly pornographic manner, as in two watercolors by the American modernist Charles Demuth (1883 - 35), Two Sailors Urinating (Figure 46, p. 150) and Three Sailors on the Beach (Figure 47, p. 1651(), and in a well-known pen drawing of two fucking sailors produced by French artist Jean Cocteau (1889 – 63) for Genet’s classic Querelle de Brest. In his book on twentieth-century homoerotic art, The Sexual Perspective, Emmanuel Cooper asserted that Cocteau’s virile "demigods" were "fantasized images of a well-developed subculture" and idealizations of "masculine" and "virile" types with "faces that seem mere masks to a lustful desire for sexual pleasure." For Cooper, Cocteau’s men "suggest the odor, attractions and rough masculine sexuality of sailors, soldiers, and laborers." The great majority of these images were not intended for public consumption, as the prevailing morals were such that any public viewing of this kind of work would likely have ended an artist’s career overnight."

Paul Cadmus, the only contemporary mainstream artist considered by Tom of Finland to have inspired some of his own work, often used sailors in his work. A typical example is The Fleet’s In! (Figure 48, p. 151), painted in 1934, which conveys the raucous demeanor of U.S. marines on shore leave. A tangible sensuality exists between these men, and the painting can be considered a coded rendering (and not very cryptic) or gay cruising. A clear clue about the picture’s homosexual contents is provided by the third character from the left, who offers a cigarette to a sailor. He is elegantly dressed and wears a red tie, a then popular code among gay men, which Cadmus repeatedly used to indicate a character’s homosexuality. The connection between Cadmus’s and Demuth’s images of sailors, apart from the obvious one of the main motif, is that both painters showed sailors" sexuality as very present in the public sphere. Indeed, as Jonathan Weinberg has pointed out, "the settings of Demuth’s homosexual watercolors – bathhouses, streets along the docks, bathrooms, and beaches – are a fairly extensive catalogue of the places gay men were able to meet." In this sense he is a direct precursor of Tom of Finland, who equally firmly situated gay sex in the public arena.

During the Second World War, sailors became omnipresent in American cities, and their (physical) presence in urban gay subcultures increased even further. This is undoubtedly one of the reasons for the appearance of strong homoerotic images of sailors in postwar underground films, such as Fireworks (1947), Kenneth Anger’s first production, in which the then twenty-year-old filmmaker explored his nocturnal fantasies (Figure 49, p. 153). In this film, the main character, called the Dreamer (played by Anger himself), is attacked by a gang of sailors. They tear off his clothes, and once naked, he is subjected to their violence. After the attack, which is followed by images of milk flowing over his body (their orgasms?), the Dreamer is seen on the floor of a urinal (which appeared earlier in the film). He is wearing a sailor’s hat. When the Dreamer reaches his orgasm – symbolized by an exploding enormous phallus – images of a sailor are again seen. The symbolic connections between sex, violence, orgasm, and sailors are every bit as explicit, thought of a very different aesthetic order, as those used by Tom of Finland in his work.

Tom’s predecessor at Physique Pictorial, the painter and illustrator George Quaintance, also regularly used sailors in his romantic-erotic work for the magazine (Figure 50, p. 154). A whole series of drawings from the sixties are typical examples of the way in which Tom continued and developed this tradition. A 1962 work (Figure 51, p. 155) shows a leatherman approaching a sailor in a bar. Their common wish is obvious from their erect penises, clearly indicated along their left legs. In 1967, Tom produced a number of drawings set in tattoo parlors. In a first example (Figure 52, p. 156), a sailor offers a tattoo artist his buttocks for decoration. Scattered across the floor are sheets filled with designs. The tattoo artist is about to start work, needle at the ready, but seems slightly distracted by his customer’s attractive physique. One of the sailor’s colleagues is contentedly waiting on a low stool. Bare-chested and in a relaxed pose, he is studying his companion’s uncovered crotch. Two laughing men, one of whom is clearly another sailor, are looking in through the window.

A second example deals with a similar scene (Figure 53, p. 157). The tattoo artist is now going about his business. He is applying a snake motif to a sailor’s upper leg. The sailor is merrily observing this undertaking, in spite of the pain that it must inevitably cause. The bulge in his briefs suggests that he is enjoying the operation. One of his colleagues is standing behind the duo, looking down and inspecting his erection, which is clearly shown in his left trouser leg. The snake, which is being engraved onto the sailor’s leg, is a potent symbol of masculinity. Although neither of the drawings discussed here contains overt sexual activity, their sexual quality is clear. Being tattooed causes erotic pain (see chapter 8) and necessitates direct physical contact between men that does not code as "homosexual" but as "male camaraderie," thus allowing all characters to be excited without causing an embarrassing loss of virility. This is enhanced even further by the openness of the scene (window) and the voyeurs. Such work cannot be but highly erotic for men who fantasize about sexual contact with men, but who have been excluded from masculinity because of their sexual identity.

As the sixties ended, sailors virtually disappeared from Tom’s drawings. In the same period, ports were moved away from the inner cities to areas far removed from downtown. Sailors often no longer came ashore in the uniforms and thus ceased to be recognizable as such. Other, exclusively gay, contact places replaced the rough bars and brothels in port areas. Until that time these were also frequented by many gay men, thus creating a mix that facilitated homosocial and homoerotic contacts in a (marginalized) straight environment. In an interview given in 1981, Tom said he had stopped drawing sailors altogether.

But the eighties would be a time of renewed interest in sailor imagery, and they returned to Tom’s drawing board. He produced enough images of seamen to fill an album, which was commercially successful. But, if sailors still figure in his work at that time, they have become a nostalgic reference to days gone by (those days long gone when men were men), as in an ad for the Amsterdam gay bookshop Intermale (Figure 54, p. 159) or as a fantasy figure, such as the one on the album’s cover. Sailors themselves no longer play a significant role in today’s gay subculture, but have become mythical figures – a symbol that nevertheless has lost hardly any of its attraction.

The renewed interest in sailors also manifested itself in a revival of this imagery, which in the seventies had all but completely dropped from view. Querelle, a film by Rainer Werner Fassbinder based on Genet’s novel, and Pierre et Gilles’s well-known candy-colored image of a cute boy sailor, as well as photographs of sailors, or at least of New York gay men sporting the uniform, by Robert Mapplethorpe, perfectly illustrate the central function this maritime iconography continued to fulfil in gay erotic fantasy. The artificiality of the characters and decors of Fassbinder’s film – which is set in a city dominated by phallic symbols (e.g., penis-shaped watchtowers), a mythical version of the northern-French port town of Brest – Pierre et Gilles’s flamboyant photo manipulations, and Mapplethorpe’s sailors, in very different ways, all point to the sailor’s unreal and iconic nature in contemporary gay culture.

Copyright © 2000

Micha Ramakers.

Back

to the Stonewall Inn

Back

to the Stonewall Inn