|

|

||||||||

| Excerpts: | ||||||||

|

![]()

From "Sexual Healing"

From "Sexual Healing"

By Noelle Howey

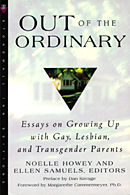

From Out of the Ordinary

It was just about my favorite game in sixth grade, second only to Hooker Barbie and Pimp Ken.

I sneak one of my Mom’s teddies – if possible, the gold one with snaps on the bottom – out of Dad’s dresser (for some reason, she keeps them in his underwear drawer), take one of Dad’s Playboy magazines from under an old copy of Newsweek in the linen closet, and lock the bedroom door.

I Scotch tape the shades to the window sill, glide on some cherry Lip Smacker and sky-blue eye shadow, stick the record needle on "Like a Virgin," and try to keep the teddy – about ten sizes too big for me – from falling off. I keep an ear out for Mom or Dad coming up the stairs.

"I know you want it," I whisper.

I crook my leg around the door frame and glide my crotch up and down against the edge. "Do it, like, hard," I growl, my hot breath forming small, moist circles on the wood.

I pretend the door frame is named Jake, and that he is a sexy, tall ninth grader who looks like the guy on the cover of the Sweet Valley High books. I try to get him to want me. It’s sort of easy in that guys always want sex but hard in that guys like big boobs and I just have these little bumps that my friend who got her period in elementary school calls spider bites.

When I am ready to have sex with Jake, it feels like I have to pee, and I hold myself like when I have to go and can’t unlock the door fast enough to get in the house.

Before I put everything away, I squat on the bathroom sink in front of the mirrored medicine cabinet and pout my glossy pink lips. I run my hands down my hairless legs, unsnap the teddy bottom, and arch my privates up toward the mirror, singing "‘Cause I’m a woman" from the Enjoli commercial, quietly so no one can hear. I grin and imagine the day, maybe in high school, when I’ll wake up and look exactly like the femme fatale of my fantasies.

While I am playing, Dad is down in the basement, a place where all dads like to be. It’s cold and made of concrete; there’s a sawhorse, a tool box, and an extra fridge filled with Budweiser. He says he is working on a project. I assume it involves shellacking an end table. It doesn’t.

My father has tucked himself in the windowless back room of the basement, the only place in the house he feels truly at home. He takes out the portable makeup mirror from behind the solvents, a cache of old dresses from under the camping equipment. He leans into the mirror, trying on a new pair of eyelashes. He slicks on Ruby Red Max Factor and puckers. When he hears a creak on the steps, he frantically starts unscrewing his jar of Pond’s Cold Cream. It’s just the cat. Exhaling, he slips into a green hausfrau number. He imagines himself done up in an apron, merrily folding the laundry for the whole clan. In the dim light of the basement, he can barely see his stubble or Adam’s apple. He runs his hands over the padded bra, trying to ignore the stray chest hairs. This is ridiculous, he thinks. He needs another drink. Stoically, he wipes all traces of the cosmetics from his face. He goes upstairs and barks at me to get away from the TV because it’s time for the PGA championship. When my mother comes home, he tells her he spent the afternoon finishing the end table.

My father is a transgendered lesbian, a biological male who thought of his Y chromosome as a cruel cosmic joke and wanted, above all things, to become a female. Over the course of my teenage years he metamorphosed into a woman through exhaustive estrogen therapy, electrolysis on every last facial hair follicle, and sex reassignment surgery. But for both of us, the process of becoming a woman was more complicated than mere physical transformation. We didn’t realize then that we would spend years unconsciously trying on and discarding different, and equally limiting, images of womanhood before we were able to create versions that fit…

I was in ninth grade when my mom dropped the news. In a halting, whispery voice she said that dad liked to wear girls’ clothes and needed to move out in order to understand exactly what that was all about. I was predictably shocked. So is dad like Tootsie? Or Boy George? It seemed impossible that my dad could be anything but a tough guy. But oddly, I felt an enormous flood of relief rush over me. So that’s why he’s such a jerk, I thought, almost giddy with the revelation. He’s a freak. Not me. I am not the problem.

Later that week, my father took me out to lunch, still wearing his same guy clothes. I scrutinized him for any noticeable signs of femininity and found only that his nails were kind of long for a guy–way longer than mine were. Over cheeseburgers and nacho fries, he told me he wasn’t just a transvestite, but a transsexual, which meant he felt he should have been born a woman. He said he had felt trapped in the wrong gender his whole life, and that’s why he had so many problems communicating with me and my mom. He still loved us, but he couldn’t live in a man’s body anymore. I nodded. I didn’t have any questions – yet…

The first crack in my purposely indifferent teen exterior came when I saw my father fully dressed as a woman. She loped up the driveway sporting nautical wear from the Gap, with a mop of brown curls and pink lipstick. She looked like the quintessential PTA mom – no Some Like It Hot drag queen here. My God, I thought, she is really doing this.

Except for having suspiciously thick wrists, there was not a single sign that she was genetically a middle-aged man. I knew she had been having electrolysis treatments, and I had witnessed the purple bruises from the eye tuck and chin life that briefly mottled her face. I also realized she had been on major hormones. But I had no idea how smoothly she could morph into a passable – even attractive – female. It scared me beyond belief. My stomach clenched when I saw her hairless arms, the small bumps on her chest. What hit me hardest, though, was spotting a thin Timex watch on her wrist where a chunky Rolex had been. My dad always wore that thick gold watch. Now it had gone, packed away in a box as though he were dead. I didn’t say a word. I hugged her tensely and ran up to my bedroom to do homework.

I wonder now if my family could have used a mourning period. My mother and I could have dressed in black and sat in the living room, being fed cold cuts and pickle spears, recalling the time that my dad got drunk at Rick’s birthday party or we got lost in Washington, D.C., and Dad swore until he turned purple. But instead, my mother and I believed our own rhetoric – that he was the same, only different, and that our family was still intact and loving, only divorced and just a little confused. We tried not to acknowledge that the change my father was making was more than cosmetic, and that even if it was ultimately for the better, it still entailed profound loss.

Copyright © 2000 Noelle Howey.

Back

to the Stonewall Inn

Back

to the Stonewall Inn