|

|

||||||||

| Excerpts: | ||||||||

|

![]()

"Charlotte"

"Charlotte"

By Meagan Rosser

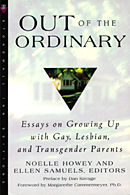

From Out of the Ordinary

As long as I can remember, I’ve been fielding questions about who Charlotte is and why she lived with my mom, my sister and me. Mom and Charlotte made it clear to us that they could lose their jobs if the wrong people found out the truth about them. My elementary school friends swallowed the story that she was my mom’s best friend who had moved in after the divorce so that they could both save money – especially since I could point to the guest room closet where Charlotte kept her clothes and tell them this was her bedroom. But as I got older, my friends began to ask why I was worried about getting busted by Charlotte if I stayed out late. "She’s not your mom, girl," they’d tease. And when my mom got a new job, and we were getting ready to move from Virginia to South Carolina, my friends just assumed Charlotte wouldn’t be coming. I ended up telling a few of them the truth. Most of them handled it well, accepting my mom and Charlotte while still making the same jokes about "fags" and "lezzies" that they always did.

As my plane hits the runway in Gainesville, I am more scared than I’ve ever been in my life. For a moment, I’m not even sure I can stand up and walk down the narrow aisle to the exit. "This won’t work," I tell myself. "You need to stay strong for Charlotte." Somehow, I manage to get off the plane and take a cab to the hospital. The driver calls me "Honey." His thick Southern accent is comforting and familiar.

I can hear uproarious laughter all the way down the hall to Charlotte’s hospital room. When I get to the doorway, I see the backs of two women sitting in chairs drawn up by the bed. They have that familiar white middle-class lesbian look: bi-level haircuts, no make-up, tailored pants, comfortable shoes. Charlotte is propped up on pillows, showing them something in her lap. As I get closer, I see that it’s a get-well card signed by her students from the middle school. Charlotte looks up and sees me standing uncertainly in the doorway. She has lost a lot of weight. Her cheeks are sunken and the circles under her eyes have darkened to a rich plum color. But her eyes and smile have not changed. "Meagan," she calls out in her warm, deep voice. "Barbara, Denise, this is Meagan, my oldest daughter!"

I lose track of the number of women who come to visit Charlotte in the hospital that day. Knowing Charlotte, it doesn’t surprise me that she has already made friends in the few weeks she and Mom have lived in Gainesville, but I am amazed that some of her visitors are women she has never even met. Ruby and Lee, two other professors at the university, introduce themselves to Charlotte and me for the first time, and then offer to help unpack boxes at the new house and run errands. I thank them for their generosity and Ruby replies "Oh it’s all right, honey. Last year one of us was in the hospital and everyone just got together to help her out."

Later that night, during Barbara and Denise’s second visit, they go out to find a ladies room, and come back looking amused. Barbara nudges Charlotte and says "I think your night nurse sings for the choir." We all giggle, and the older women talk about various other people around town who might "bat for the team" or "go to their church." When Charlotte starts speaking less and closes her eyes for a few minutes, Denise stands up and touches me on the arm. "Come on, Meagan," she says cheerfully. "I’ll give you a ride back to the house, and we can stop on the way for some dinner."

Over heaping plates of genuine Southern barbecue, I confess to Denise how worried I am about Mom. She has never been single in her entire adult life, and it is really hard for me to imagine her without Charlotte. "Don’t worry honey, we’ll all make sure they both get taken care of," Denise tells me in her soothing drawl. It is the first time that I’ve ever been in Gainesville, but I feel nearly at home.

Five minutes after I walk back into my apartment in Boston, the phone rings. It’s Grandmother Rosser. I drop my heavy duffel bag next to the couch and sit down. Grandmother is excited to tell me that three of her compositions for violin and piano are being performed in public soon. I close my eyes. All I can think of are the green walls of the hospital room, the pain in Charlotte’s face as she struggled to sit up, the way her hand sat heavy on my shoulder while I steadied her. Then Grandmother asks briskly, "So, was it warm down in Florida? How is your mother liking it?"

Something inside of me snaps. Once I begin talking, I can’t stop: "Well, I think Mom is doing pretty well considering that her partner of eighteen years is dying of cancer. Even if you don’t approve of Mom and Charlotte’s relationship, if you love Caitie and me, then you have to understand what is going on for us right now. We are losing a parent."

It was the first time I’ve ever known Grandmother to be at a loss for words. A few minutes pass, during which I can hear my own breath hiss into the receiver. Finally, she says, "Darling, you know that you’re a dear sweet girl and I love you."

We hang up soon after.

But in her own way, Grandmother shows me that she got the message. For the next few weeks, every time she calls, she asks about Charlotte. And five months later, she sends flowers for Charlotte’s memorial service, a sheaf of white irises that stand tall among the others.

Copyright © 2000

Meagan Rosser.

Back

to the Stonewall Inn

Back

to the Stonewall Inn