|

|

||||||||

| Excerpts: | ||||||||

|

![]()

"Smile and Say Nothing"

"Smile and Say Nothing"

By Ian

Wheeler-Nicholson

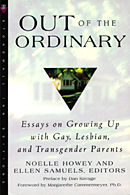

From Out of the Ordinary

On a September morning about twenty years ago, I stood rocking back and forth impatiently, nervously, on the front lawn of our house while my mother buttoned up my jacket for the first day at my new school. I was used to the routine. Every summer we would move to a new town and I would enroll in a new elementary school, having to memorize whole classrooms full of children who had shot spitballs at each other since preschool. I was well acquainted with the hostility of children to newcomers, and so, once again, I had the jitters.

"Now, listen," my mother said, taking me a little roughly by the shoulders, so that I’d pay attention. "If anybody asks you where your father is or who you live with, don’t tell them anything." And with these quick and cryptic words, she pushed me, confused now as well as nervous, down the path to the school bus.

My mother had never been good at communication. She was a reserved woman who kept her secrets to herself. On this occasion, however, I sensed that she was trying to tell me something important. I had no idea what it could be.

I stood awkwardly at the bus stop with a group of six or seven other children, some in fourth grade like me, others as old as sixth graders. They talked furiously among themselves about summer camp and Boy Scouts and cast suspicious glances at me. A couple of the boys started an energetic game of catch with a worn-out softball but did not invite me to participate. With my mother’s strange warning still ringing in my ears, I was nervous that somebody would approach me suddenly and ask me, "Where’s your father? Who lives at your house?" although I didn’t know why these questions should be feared.

On the way to school, sitting self-conscious and alone in the front of the bus while chaos ruled the seats behind me, I thought about what my mother had said. But why would anyone care where my father was? He was in New York City, where he had lived since my parents divorced when I was an infant. I had no memory of their ever having been married, in fact, and privately doubted that such an absurd thing could be true. And whom did I live with? My mother, of course, and Veronica, a woman around my mother’s age with whom she shared a bedroom. Veronica wasn’t my family, but she had always been there, at least as long as I could remember.

In this new, rougher school, I began hearing playground slang previously unknown to me. Among the tough Irish and Italian boys of this working-class town, "homo" and "faggot" were the worst sort of insults one boy could throw at another. It was understood that calling a boy a faggot was serious, the kind of remark that makes other kids shut up and wait to see what happens.

What the word actually meant was not clear to me at first, but I soon came to understand that it referred to a peculiar species of man that had sex with other men. The whole concept of sex itself was just breaking over my consciousness at this period, and it seemed absurd and grotesque enough without this added information. As easily disgusted and titillated as boys my age were by anything grossly sexual, we were reduced to hysterics at the idea of faggots.

There was more. These words, faggot and homo, were only supposed to be used in reference to men. There were special words for women: dyke and lesbo. This latter one was apparently short for some longer term, vaguely scientific, but I didn’t learn that word, with its strangely classical connotations, until later. The idea was clear, however. Dykes were freaks, women who did it with women.

Accusations would fly at any female who wasn’t girlie enough. Whenever a girl showed any guy tendencies – a good throwing arm or perspiration – she could be branded a dyke. Ironically, every now and then, a girl who was ultrafeminine might be considered dykey, too. For example, I remember a group of boys taunting a girl as a "lesbo" during gym class one day because she was not only exceptionally good at softball but also had begun to grow breasts.

This business about dykes cut a little close. After working out just what a dyke was, I remember feeling an uncomfortable coldness in my chest. Along with my rudimentary understandings of the mechanics of sex, I had stumbled upon an uncomfortable truth: my mother, apparently, was a dyke. Suddenly, when she came home from work, I looked at her with a mixture of fear and embarrassment. I knew something about her that nobody else knew, something that was wrong, at least according to the conventional wisdom.

Maybe it was an indication of the distance between my mother and me in those days that I didn’t ask her about any of this. Looking back, I can see that my mother was going through a hard time herself, trying to find a new identity after years of an unsatisfying "straight" marriage. Her ability to provide emotional reassurance to me was limited, and her attention to the details of parenting was sometimes perfunctory. Only later, when she had achieved a greater degree of self-acceptance, could she look at me and see how I was doing. But when I was ten years old, I had no one to turn to for advice on dealing with gay people or those who hated them.

What was obvious to me – as it had been to my mother – was that I had to keep the fact of her lesbianism a complete secret. As a new kid, neither rich nor athletic, I was already at a disadvantage in this town; if people learned that my mother lived and slept with another woman, my fragile reputation would be finished, and I would likely be in for a serious whupping.

I knew what my mother had been afraid of: that, in my innocence, I would give away information that might get me into trouble. "Oh, my dad’s gone, and I live with two women." She had been right to warn me. In those days, in that town, homosexuals had one choice: keep silent and hope nobody finds out. My mother never wanted to make me complicit in her own personal deception, but she simply had no choice.

And so a cloud of invisibility settled over our little ranch house on our little street of identical lawns. We were the neighbors nobody ever saw. My mother and Veronica commuted to work in other towns and made no connections among our neighbors. I had no friends. I had never been popular anyway, always being a newcomer, not to mention introverted and a little weird, so it was not too difficult to avoid other kids and their uncomfortable questions.

There were inconveniences, of course, to this secretive life. Halloween, for example – the one day on which the neighbors who otherwise never speak to one another persist in dragging their costumed children up and down the street, ringing doorbells for costumed children up and down the street, ringing doorbells for miniature Mr. Goodbars and Skittles – was awkward. It would not do for a group of children and mothers dressed as witches and vampires to come to our door and see our little domestic scene: Two Women and a Baby. It became our family tradition to go out to dinner and then to a movie on Halloween, not returning to our home until the neighborhood ghouls had been safely tucked in.

Copyright © 2000

Ian

Wheeler-Nicholson.

Back

to the Stonewall Inn

Back

to the Stonewall Inn