|

|

||||||||

| Excerpts: | ||||||||

|

![]()

"I Remember

Reaching for Michael's Hand"

"I Remember

Reaching for Michael's Hand"

By Stefan Lynch

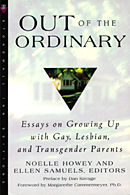

From Out of the Ordinary

Today I was waiting to pick up my lunch outside a restaurant in downtown San Francisco. There was a man my age sitting on the ground who (I found out later) was also waiting for his lunch. Suddenly, another man, whose eyes were bloodshot and clothes looked slept in, began to punch and kick the man on the ground, yelling at him as if he knew him, saying "Don’t you ever mess with my shit again!" I stood frozen for a moment, then I began to yell at the punching man: "Stop it! Leave him alone!"

He kept kicking the man on the ground who curled up in a ball, protecting his face. The attacker started to walk away, distracted, but then he turned around and took a running leap into the air and landed on the man on the ground, lost his balance and fell down – dazed. Others joined in the yelling, and we got him to stop.

I knelt down to the man on the ground and sat with him while he cried. His hands were shaking when I gave him the piece of jewelry that had been knocked from his bleeding ear; he was hurt but not seriously. Then the police showed up.

They had the attacker in custody and wanted me to make a statement. The officer asked for my ID, my phone number and my name, but I didn’t want to tell him. I wouldn’t have told him anything at all, but I wanted to show my support for the beaten man. My own hands began to shake as I handed the cop my driver’s license and told him how to reach me. In the face of a violent assault, I was more frightened of the police than of the perpetrator.

My gay family never called the cops when I was growing up. The only assaults our friends reported to the police were assaults by the police. When my dad was punched in the face by a former student screaming, "Faggot!" he did not report it. I was around thirteen at the time, and I definitely had the sense that, while it wasn’t OK for this man to get away with beating up my dad, there was no recourse. The overall sense among my dad and his friends was that, if you were gay, these things happened. Living in Toronto throughout middle school and high school, I was terrified of people finding out about my parents, partly because I might be rejected, but also because I dreaded violence. It’s only since living mostly free of that fear that I have recognized its full impact. At the same time, the years I’ve spent living with my very-closeted mother have taught me that the shame of the closet is much worse than the openness of my dad’s life, even if the act of being honest made us vulnerable to violence.

When I hid the truth about my family, I thought it was because I didn’t want to be ostracized. I was a bit nerdy and awkward and out of place already without adding to it by outing my parents. But now I can more fully appreciate how my anxiety about the threat of antigay violence motivated my silence. I only caught a glimpse of that anxiety’s true weight once or twice a year: usually at a Gay Pride march when every step felt lighter, like a weight I didn’t know was there had gone away. A friend’s dad told her after he came out that "You have to be careful who you tell, there are people who would kill me if they knew." My dad never said those words, but he didn’t have to: it was obvious.

I remember the subway car pulling to a stop, the people inside swaying, and the people outside jockeying for position next to the doors. I remember reaching for Michael’s hand – I always called both my parents by their first names – as we got off the subway train. I didn’t want to be separated from him, although I got off the subway downtown every school day by myself. Usually there was a crush of men and women in suits hurrying to bank jobs on Bay Street or law offices on Front, but this was the middle of the afternoon, an unusual time to be arriving, unusual people going about their business: shift-working West Indian women in their blue uniforms and practical shoes, young couriers with enormous bright bags covered with logos, drunks who rode the same train around and around in sleepy laps across Toronto.

On my dad’s other side he carried his bag, a leather satchel that looked enough like a purse that I was sometimes embarrassed by it, even though my parents had told me it was OK. Unlike my mother’s purse, which was filled with tissues, tiny folding scissors in silk pouches, yogurt-covered peanuts, and loose change, Michael’s satchel only ever held the material of the moment: fresh cheese, green beans, and European sausages bought from vendors in Kensington Market; essays graded in green pen to return to his students.

I remember climbing the stairs to the street slowly so that the other riders would pass. We stopped and my dad let go of my hand, reached into his satchel, pulled off the rubber band that kept the stacks of rectangular white stickers neatly in order, brought one out, peeled off its backing and–with a focus which I think was determination not to look behind him–stuck the red-on-white decal at eye level on the green tile wall. It read in bold capitals:

NO MORE SHIT!

GAYS BASH BACK!

The image of it, stuck there for anyone to see, still burns in my mind’s eye. I didn’t understand all that was going on, but I did know that we were in the middle of some kind of fight, that my dad was gone most evenings until very late, that the phone was constantly ringing as I carefully wrote down the messages from lawyers and reporters and friends as my dad had taught me to do; they kept wanting me to read back what they had said. Remembering these things, I want to know more.

Michael, my father, is dead now, so I e-mail Rick, a friend of his with an encyclopedic memory who lived through those times in Toronto. I ask him to help me reconstruct a brief history of that time when, with my dad, he was part of the collective that ran the gay newspaper called The Body Politic. He tells me about the Web site of the Canadian Lesbian and Gay Archives where he and others have posted timelines and essays about this period. It makes me feel old to have lived through something now considered history.

Copyright © 2000

Stefan Lynch.

Back

to the Stonewall Inn

Back

to the Stonewall Inn