Dogs and ESP

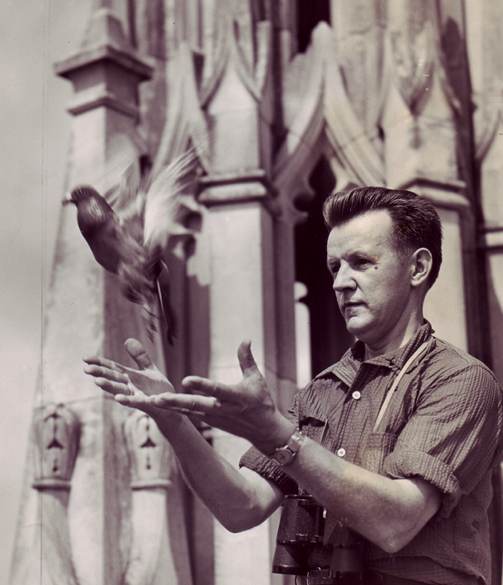

I think this post might be partly an excuse to post a picture of these adorable puppies. I got it from the San Francisco Chronicle. It’s a picture of dogs who are being trained to detect land mines. In 1951, the Army and J. B. Rhine conducted an ESP test using dogs to detect land mines.

It was following WWII and by the time land mines were made with plastic and plastic explosives and the Army’s metal detectors were useless. “The guys in the field were reduced to physically probing for the mines under the surface by using their bayonets to see if they would hit a solid object,” Dick Lowrie emailed me. He was a member of the Army’s Engineer and Research Development Center at the time and they were investigating the problem. “This was deadly to the guy that makes the slightest mistake,” he explained. They had another potentially lethal method which involved a metal detector mounted in a fiberglass box on the top of a jeep. “No one was eager to drive those jeeps.”

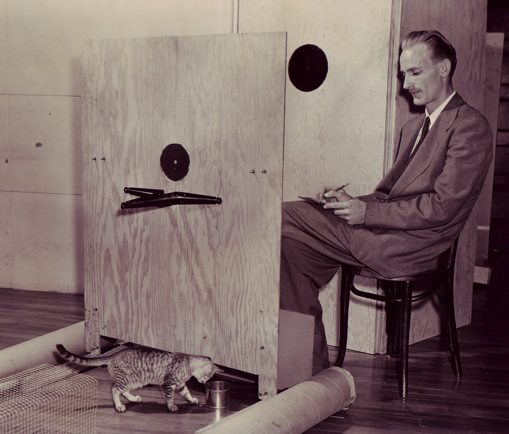

Nothing they tried was working and they were desperate to find something, anything, that would do the job. Lowrie’s section chief was the first one to bring up ESP. Lowrie had always shown an interest in the subject so he was made the project engineer. Lowrie wrote a small contract for $50,000, (small for the Army, not so small for the Lab) and he and Rhine went to work on a test to see if dogs could detect land mines using ESP.

They placed twenty mines at random locations along a smooth and breath-taking stretch of beach in Monterey. “The handlers took the dogs along the line of the beach where the mines had been planted and the dogs would sit when they sensed a mine and were given a reward if correct.” The dogs actually did better than chance, but it wasn’t reliable enough for the field where errors meant the difference between life and death. They needed a lot better than above chance.

(The picture was taken by Vinh Dao.)