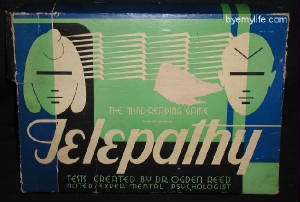

In 1939, Rhine learned that the toy company Cadaco-Ellis was planning to come out with a game called Telepathy. The creator was said to be a psychologist named Dr. Ogden Reed.

J. B. Rhine suspected and confirmed that Reed was really Dr. Louis D. Goodfellow, a Northwestern University psychologist who had been hired by the Zenith Radio Corporation in 1937 to conduct ESP tests on the radio. Rhine had been hired as a consultant for that same program, and he had had no end of trouble with Goodfellow. Rhine felt Goodfellow had not inserted sufficient controls into the experiment and had made mistakes with the math. Goodfellow was eventually let go.

Goodfellow apparently had hard feelings toward Rhine because in the pamphlet that came with the game he wrote, “Dr. Rhine’s first experiments were full of loopholes. For example, it was found that the ink with which the cards were printed caused the paper to shrink, etc.” As far as I know, the example Goodfellow gave was untrue, and while like any experiment, problems with Rhine’s initial experiments had to be identified and addressed, Goodfellow’s bringing it up in this way does feel a little like payback.

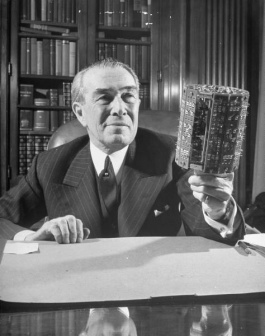

Commander Eugene F. McDonald, the head of Zenith, was so incensed by what Goodfellow had written that he told Rhine that he should bring action against Cadaco-Ellis and that he, McDonald, would foot the bill.

Rhine, meanwhile, had written Goodfellow and asked, “Is it proper for an academic man to use a surreptitious approach (in this case, an assumed name) to avoid having to meet the responsibility for the things he is expressing?”

Goodfellow answered that the company did use “a number of my own expressions,” however the creation of a Dr. Ogden Reed was the toy company’s idea, not his. Rhine answered that he had two signed statements from people in a position to know that Goodfellow was the sole author of the statement penned by “Dr. Ogden Reed.” If they removed the controversial matter, Rhine told him, they’d have no problem, “poor as its design really is” for telepathy. But if they released the game as is, they’d “take steps to bring you out in full light as author of an underhand attack and as party to setting up a fake “authority” as a psychologist.”

I found one funny letter referencing this incident from Robert H. Gault, a colleague of Goodfellow’s at Northwestern. Gault wrote McDonald: “Rhine and Goodfellow keep me supplied with carbon copies of their love letters. I’m not surprised that R. is up on his ear. Between you and me and the gate post, I don’t care what kind of spanking he administers to G. The latter is an excellent technical man in the laboratory and in that capacity he is useful to me. But in some other respects he is a damn fool … I’m telling him after today that hereafter I want to know what he is about, provided it is something that by any chance could affect relations outside the laboratory.” Gault went on to write books about criminology.

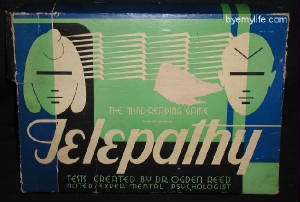

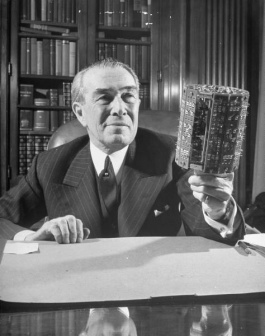

I found the picture of the Telepathy game on http://byemylife.com. The picture to the left is Zenith president Eugene McDonald.

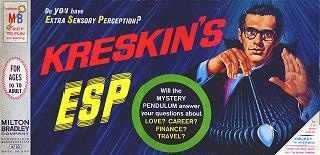

While I was looking for the picture of the Cadaco-Ellis game I came across this modern telepathy game. And this one pictured below from Milton Bradley.

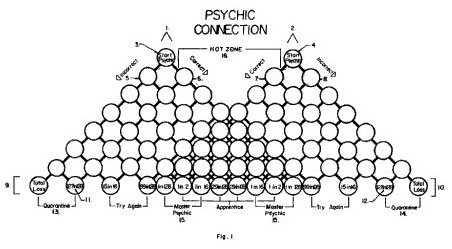

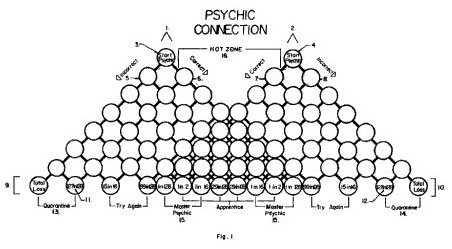

And speaking of telepathy games, I happened to be researching patents a few weeks ago (about something unrelated to anything paranormal) and came across a 1984 patent for a “psychic connection game.” It was developed by Laurie G. Larwood, who, if I’m googling properly, was an organizational psychologist.

From the abstract:

A game for evaluation and development of various psychic abilities between its participants. Objects are furnished which include bi-valued dimensional attributes, such as rough-smooth, solid-hollow, or heads-tails. A player concentrates on a chosen attribute and attempts to either transmit, receive, block, predict, or influence a given valued condition.

A gameboard is provided on which a player’s successes are marked by position of his player-piece or counter on the board. Counter positions are marked with the chance probability of reaching a given position from a start position in a given number of moves. Board layout is such that if the incidence of successes is greater than that expected by random chance alone, counters are moved toward another player, thereby establishing a higher degree of psychic connectivity.

This is one of the drawings that was filed with the patent.