On June 26, 1957, The New York Times ran a piece by Meyer Berger about a haunted house in the West Village called: Ghostly Coincidences Puzzle Bohemian Couple in 125-Year-Old House in Greenwich Village.

Briefly: Harvey Slatin bought the red brick house and was in the process of converting it from a rooming house into a single family home. The Slatins and the constructions workers sometimes heard what sounded like a woman on the stairs. At first they just figured they had an intruder, and they’d wait to hear the sounds and then run upstairs. But no one was ever there. Their carpenter wrote it off to the odd sounds you hear in old homes.

Slatin wasn’t particularly unnerved either, and instead tried to study the phenomena. He timed her ghostly steps and noted that they began at 11 in the morning and continued off and on until dusk. “I’d call them rather friendly sounds; a wee bit spooky, maybe,” he said, “but somehow not frightening.”

Later, when the carpenter was removing the ceiling on the top floor, a small tin about the size of a can of coffee fell onto his head. The label read, “The last remains of Elizabeth Bullock, deceased. Cremated January 21, 1931.” Slatin called the crematorium listed on the container and learned that Elizabeth Bullock had been hit by a car on Hudson Street, and taken to a drugstore nearby where she died. She had lived on Perry Street though, and no one could explain how she ended up in a ceiling on Bank Street, and they weren’t able to learn anything else about her.

(The picture above is the Bank Street building where the actual haunting took place. The one below is the Perry Street building where Elizabeth Bullock was living before she died.)

Ghost hunter Hans Holzer (who died this year) read Berger’s piece and contacted the Slatins to offer his services. During a seance conducted in the building, Holzer and his favorite medium, Ethel Johnson Meyers, came up with more (alleged) information about Elizabeth Bullock, which I have since researched. I love fact checking seances.

This particular seance had an interesting mix of hits and misses. One thing that came out of the seance was Elizabeth Bullock’s wish to have a Christian burial, which she had been denied because she married outside her faith. Holzer’s account ends with his suggestion that they bury her in the garden. The Slatins say they’re going to keep the tin with Elizabeth’s ashes displayed on the piano, where she’s happy they insist, but also in case someone shows up to claim her.

In 2007 I tracked down Harvey Slatin, who turned out to be Dr. Harvey Slatin, a Manhattan Project nuclear physicist. He was now 92 years old, and not terribly interested in talking to me, but he did tell me enough so that I could research the story more thoroughly. More importantly, although Dr. Slatin doesn’t believe in ghosts he confirmed the unexplained events at Bank Street, so whatever the final explanation, they happened.

The seance at Bank Street took place on a weekday evening in July. Mrs. Meyers went into a trance and immediately connected with a spirit named Betty who she said was paralyzed on one side and walked with a limp. Slatin’s wife Yeffe was thrilled. She told them that she’d seen a lady with a limp with her “psychic eye”.

The spirit named Betty told her story, but like many stories told via mediums, her narrative is confusing. “He didn’t want me in the family plot—my brother—I wasn’t even married in their eyes … But I was married before God … Edward Bullock … I want a Christian burial in the shades of the Cross … any place where the Cross is—but not with them!” Betty gave a few details about her life: her mother’s maiden name was Elizabeth McCuller, and they came from Pleasantville, New York. When asked why her ashes were in the attic of Bank Street she gave an answer which didn’t clarify anything. “I went with Eddie. There was a family fight … my husband went with Eddie … steal the ashes … pay for no burial … he came back and took them from Eddie … hide ashes … Charles knew it … made a roof over the house … ashes came through the roof … so Eddie can’t find them.”

(This is where Elizabeth died. It was a drugstore at the time.)

It’s all a bit impenetrable. “Just because I loved a man out of the faith, and so they took my bones and fought over them, and then they put them up in this place, and let them smolder up there, so nobody could touch them …” Who cremated you, Holzer asked. “It was Charles’ wish, and it wasn’t Eddie’s and therefore they quarreled. Charlie was a Presbyterian … and he would have put me in his church, but I could not offend them all. They put it beyond my reach through the roof; still hot … they stole it from the crematory.”

A few more facts emerged. She had two children, Eddie, who was alive and living in California, and Gracie, who died as a baby. Also, “Betty” spoke the entire time with an Irish brogue. Holzer said he could tell an actor from the real thing and this was the real thing. The spirit’s last words were, “Lived close by. Bullock.”

Hans Holzer and the Slatins didn’t have the benefit of the Internet and resources like Ancestry.com to help them research Elizabeth’s history. Also, enough time has gone by that Elizabeth’s death certificate is now in the public domain. What’s interesting is how much Ethel Johnson Meyers got right. Elizabeth’s husband was Edward Bullock. In Holzer’s account he said her husband was Charlie, which was a reasonable guess based on the spirit’s rambling monologue. The names Eddie and Charlie kept coming up and it was hard to tell who was who. But in fact, Elizabeth’s husband was Edward Bullock, practically the first name out of the spirit/Ethel’s mouth. And Elizabeth had a brother—his name was Charles.

After that, most of what was learned by both normal and supernatural means turned out to be wrong. Elizabeth Bullock did not die as a result of being hit by a car. The death certificate says “chronic myocarditis,” which is an inflammation of the muscle walls of the heart (but she did die in that drugstore). She also didn’t speak with an Irish brogue. Elizabeth was born in New York and her father was German and her mother, whose maiden name was Mary Schwieker, not Elizabeth McCuller, was born in the United States.

Elizabeth and Edward didn’t have any children that I could find, and New York does not have a death certificate for a child named Gracie Bullock.

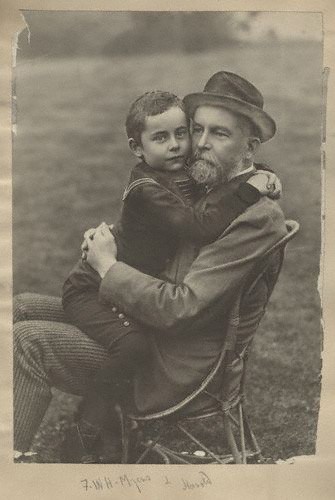

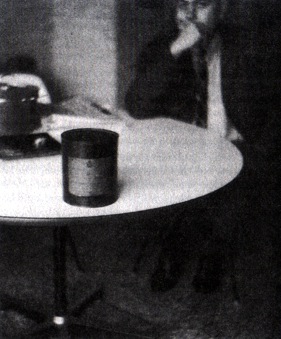

What I was most curious about was: whatever happened to the tin of ashes? (Pictured at left, scanned from one of Hans Holzer’s books.)

Slatin told me that The Washington Post did a piece about their ghost in 1981. A few months later the Slatins got a letter from a northern California priest named Devereaux. Father Devereaux offered to have a service for Elizabeth and to bury her in St. Patrick’s Cemetery at Table Bluff, in Humboldt County, California. “Elizabeth will be resting with many of her own countrymen, in a very beautiful little cemetery,” he wrote. Some of the tenants at Bank Street didn’t want to see her go, she was a New York ghost after all.

I asked Slatin why they never arranged for a Christian burial before this since this was what the spirit said she wanted. He said they’d taken Elizabeth’s remains to a Catholic church in the city, but the church refused to bury her because she had married outside her faith. I hung up the phone, but then it hit me. Not only was this church being rather uncharitable, if what Slatin said was true, they were basing their decidedly uncharitable decision on information gained from a seance! This whole marrying outside her faith thing was never confirmed outside the seance.

The Slatins decided that laying her to rest as she desired was the right thing to do, and so over their neighbor’s objections they shipped her ashes to California. Fifty people attended the funeral mass at Father Devereaux’s church in the town of Loleta. Like a movie, it poured the day they buried Elizabeth. During the seance Betty had said, “I want a Christian burial in the shades of the Cross.” And so they very kindly buried her beneath a cedar cross.

Update: Nancy Wallace sent me pictures of Elizabeth’s grave which I posted here.

How Elizabeth ended up in a ceiling at Bank Street when she was a resident of Perry Street remained a mystery. But 21st century technology is a wonderful resolution-provider. According to Edward Bullock’s World War II draft registration card, now available online, sometime after Elizabeth died, Bullock moved out of their Perry Street apartment and into smaller, more affordable accommodations in the rooming house at Bank Street. Why her tin of ashes were stored in the ceiling, I can’t say.

During our brief phone call Dr. Slatin, who doesn’t believe in God or an afterlife, nonetheless admitted to me, “I felt her presence.” The air in the apartment filled with cheap perfume whenever she made her appearance known.

NOTE: There’s no point in banging on the door of this building with the hope of experiencing a haunted house. Whatever was causing the disturbances, they stopped decades ago.

AND: Here is a picture of the Bank Street Building in 1942.

AND: If you like the kind of research and writing that went into this piece, you can buy my book … here!

Finally, here’s a short movie I made of the site described and pictured above.