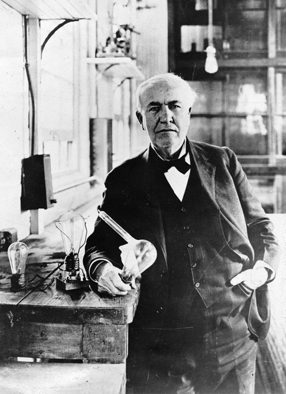

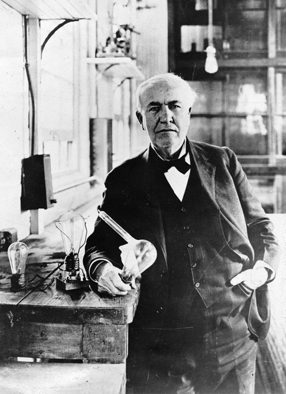

In my book I briefly mention the interview Thomas Edison had with Scientific American about a machine he wanted to build to talk to the dead. While I was researching this section I talked to Jack Stanley, the curator of the Thomas Edison Menlo Park Museum at the time. He said Edison was putting on a show for the reporter. “He was 50% business and 50% show business.” Getting his name in the papers, getting everyone talking was good for business essentially.

A 2004 National Parks Service article essentially says the same thing. “This seems to be another tall tale that Edison pulled on a reporter. In 1920 Edison told the reporter, B.F. Forbes, that he was working on a machine that could make contact with the spirits of the dead. Newspapers all over the world picked up this story. After a few years, Edison admitted that he had made the whole thing up. Today at Edison National Historic Site, we take care of over five million pages of documents. None of them mention such an experiment.”

The National Parks Service is referring to a different interview, one with The American Magazine, and they got the name of the writer a little wrong. B. F. Forbes was actually B. C. Forbes, the founder of Forbes Magazine. (It’s probably just a typo, c and f are right next to each other.)

Aside from a single reference by an unnamed “friend” who said that Edison said it was a hoax, I found nothing to truly confirm that this was a either a pr stunt or a hoax, or that Edison later took it back. Instead, what I found was that Edison continued to talk about the possibility of an afterlife until the day he died. Not as something he believed in per se, I don’t think he did, but it was something he though about, and theorized about, and he didn’t rule the possibility out.

In 1947 Edison’s son-in-law, John E. Sloane, while trying to downplay his father-in-law’s connection to the paranormal, said something that sounds closer to the truth: “Mr. Edison was interested in psychical phenomena only inasmuch as he was interested in everything.”

In other words, he was interested. Maybe curious is a better word. It was a puzzle to be solved. An unanswered question. That’s the sense I got from the Scientific American article. I loved how when Edison’s views were published on October 30, 1920, the Scientific American editors were so concerned for their own reputations they felt they had to explain themselves at the beginning of the piece in a box that was outlined twice for emphasis.

“When a man of the standing and personality of a Lodge [a respected British physicist who had also come out saying he was researching life after death] or an Edison interests himself in a subject, the public is never cold to the announcement of what he is doing and what he hopes to accomplish. So when the news went out, the other day, that Edison was carrying on experiments looking toward communication with the dead, the newspapers gave the item a place out of all proportion to that which its intrinsic importance in the scientific progress of the day and the stage to which Edison’s work has progressed would have entitled it. In this they were quite right, because their readers were interested in the bare news that Edison was working on the problem. We believe that our readers, too, are interested in what Edison is doing in this field and what he has to say about his theories and work. Hence this interview, in which Mr. Edison, himself, tells us what he believes about survival and why he hopes to establish communication. And if one thing stands out clearly beyond all other things in this interview, is that regardless of the manner in which sensational newspaper stories may present the matter, Edison stands for a return to sanity in our attitude toward the possibility of survival of personality and communication with those who may have survived.”

What actually stands out is that Edison believed it was possible.

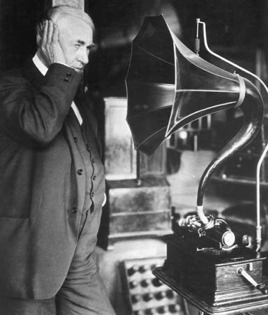

While it’s clear is that he is anxious to distance himself from spiritualists and mediums, it is only because he thought better, more scientific devices could be constructed. “In the first place,” Edison begins, “I cannot conceive of such a thing as a spirit. Imagine something that has no weight, no material form, no mass; in a word, imagine nothing!” His problem with the perhaps non-physical nature of the afterlife reflected science’s problem with the afterlife, which continues today. He goes on. “I cannot be a party to the belief that spirits exist and can be seen under certain circumstances, and can be made to tilt tables and rap, and do other things of a similar unimportant nature. The whole thing is so absurd.”

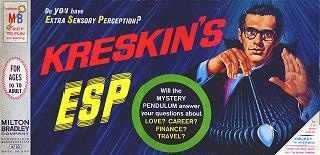

“In truth, it is the crudeness of the present methods which makes me doubt the authenticity of purported communications with deceased person. Why should personalities in another existence or sphere waste their time with a little triangular piece of wood over a board with certain lettering on it? Why should such personalities play pranks with a table? The whole business seems so childish to me that I frankly cannot give it my serious consideration.” But then he immediately goes on to say, “I believe that if we are to make any real progress in psychic investigation, we must do it with scientific apparatus, in a scientific manner, just as we do in medicine, electricity, chemistry and other fields.”

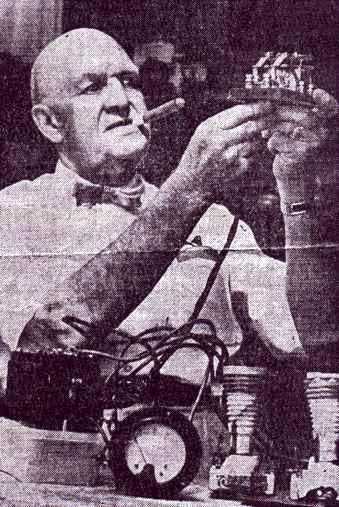

“Now what I propose to do is to furnish psychic investigators with an apparatus that will give a scientific aspect to their work.” He then explains a theory he has about what happens to us when we die, and talks about the machine he has been working on for some time with a colleague, and how it will operate.

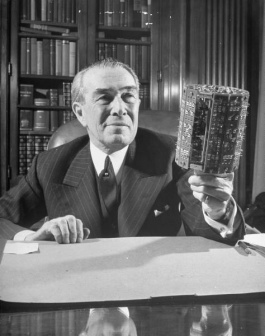

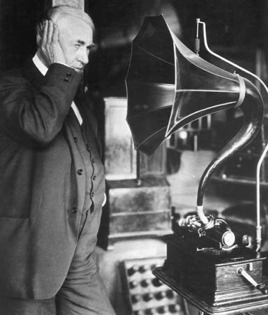

The machine he described, which was never built, was essentially a phonographic device with a very sensitive diaphragm. When I spoke with curator Jack Stanley he pointed out that the phonographic devices at the time couldn’t record the living very well, much less the dead. They recorded acoustically using a horn.

Edison’s idea about what happens when we die is at least as out there as some of the other ideas I’ve heard researching this book. He had this theory about something he called the “unit of life,” which has intelligence and propagates in some way (I don’t know how). “Man is not the unit of life,” he told a Boston Globe reporter in 1927. “I have stated that many times, but no one understands. Man is as dead as granite. The unit of life consists of swarms of billions of highly organized entities which live in the cells. I believe at times that when man dies, this swarm deserts the body, goes out into space, but keeps on and enters another and last cycle of life and is immortal. The origin and meaning of life will not be solved for centuries.” It sounds like reincarnation, and sounds even more so in the Scientific American article.

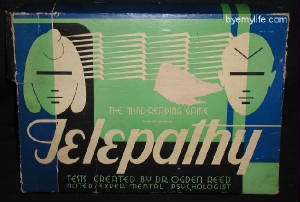

Edison didn’t believe in telepathy, at least not telepathy in the way that J. B. Rhine envisioned it. Although when asked, “Do you believe in mental telepathy, and do you think it will become a means of human communication,” he answered, “At present I don’t believe it.” Which seems to indicate he at least had a little bit of a wait-and-see attitude. It’s important to note that Edison died in 1931, years before Rhine first published the results of his ESP experiments.

By the way, I found a letter in the Parapsychology Lab archives at Duke where Rhine mentions Edison and a physicist in Detroit named Fitzgerald. According to Rhine, Fitzgerald said he has read the notes of Edison, Dr. Charles P. Steinmetz (a scientist who collaborated with Edison) and Nikola Tesla (a physicist and engineer) and was going to build the machine that Edison described in the Scientific American article. I couldn’t find anything more about it, although admittedly I didn’t try too hard. It felt like another journey for another day.

One last thing. Edison repeatedly said he didn’t believe we had a soul. Towards the end of his life his attitude about that softened. In a 1926 New York Times piece the reporter writes, “Though he does not admit that evidence of any weight in one direction or the other now exists, he thinks that the indications are favorable to the existence of a soul rather than against it.” Then, according to a New York Times reporter, Edison urged religious leaders to find evidence that can’t be easily ridiculed by the skeptical. That’s because Edison knew how the scientific community worked. So forget about ouija boards and table rapping, a better way had to be found.

The very next year J. B. and Louisa Rhine arrived at Duke University and began their experiments.