The letters received at the Lab gave me such an amazing picture of the people in this country, both good and bad.

Seventy-five foreign students from twenty-two countries had come to Duke in the summer of 1954 to enroll in various programs at the University. They were promised a swim and a picnic to get away from their studies one day, but all the public places in Durham were out of bounds due to the Jim Crow laws at the time and not all of the visiting students were white. The Rhines were then living on a farm by a lake, and the Duke Administration appealed to them for rescue (J. B. Rhine ran the lab). Rhine was more than happy to oblige. The students came to the farm for the day and swam, played softball and J. B. and Louie joined them in the evening for singing.

I couldn’t get over the fact that while some people were working on the discovery of an expanding universe and others a possible sixth sense, there were people who thought the best use of their time was putting through and maintaining legislation preventing black children from swimming in a public pool.

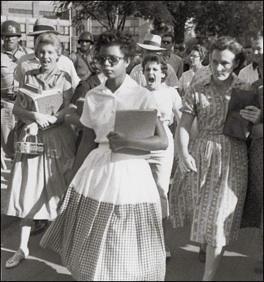

In 1957 Rhine wrote a letter to the editor of Life Magazine in response to pictures they’d recently published of the Little Rock Nine. The Governor of Arkansas had called in the National Guard to prevent nine black students from entering Central High School in the town of Little Rock. A federal judge ordered them to withdraw, and President Eisenhower brought in 1,000 members of the Army’s 101st Airborne Division to escort the children to class. Crowds showed up to shout, yell, jeer and spit at the children. One journalist wrote that student, “Elizabeth Eckford’s dress was so full of spit she was able to wring it out.”

Rhine wrote a Letter to the Editor saying, among other things, “The desperate courage of the storming of the Bastille and the riots of Poznan burst spontaneously from the ignition of group emotion. But these children have to walk calmly and coolly out to meet tormenting and humiliating attacks that hurt to the very soul. I cannot recall that there has ever been a more inspiring demonstration of courage by the children of any race, any age … Salute them and I think others will take heart and go over and stand beside them. It may help us to believe this is the home of the brave, perhaps more than it is the land of the free.”

When Life printed his letter, some people predictably did not respond well. A man in Georgia wrote to say that the word “nigger” wasn’t so bad, and scoffed at what he called Rhine’s “emotional tizzy.” But most people responded positively, like Duke alumnus (Law, 1937), and then Vice President Richard M. Nixon, who wrote to say, “I think there has been far too much discussion of the legal problems involved in this crisis and not enough emphasis on the human factors. Your letter will help immensely in bringing about a more proper balance in the public mind.”

After that Rhine and Nixon corresponded for a brief time about the human spirit and, surprisingly—I say surprisingly because I grew up during the Nixon years—Nixon wrote about the importance of protest and rebellion.