Morey and the Astronauts

In 1963, Morey Bernstein had a visit from astronaut Alan Shepard. Shepard was interested in parapsychology, “But these boys have a very tight tongue when it comes to talking about ESP effects in space,” Morey wrote J. B. Rhine. In 1971, Alan Shepard would walk on the moon with astronaut Edgar D. Mitchell, who would try to “send” messages back to earth. Two years later Mitchell founded The Institute of Noetic Sciences, which he established in order to scientifically study paranormal phenomena. By the way, Mitchell has been in the news this week for saying we’ve already been visited by aliens.

Shepard didn’t want to talk about ESP during this visit, and he didn’t want to talk about a 1956 Naval report that Bernstein had just read called The Break-Off Phenomenon: A Feeling of Separation from the Earth Experienced by Pilots at High Altitude. The study reported that 48 out of 137 Navy and Marine pilots questioned described having had an out of body experience while flying, although the authors didn’t call it that and were somewhat vague on the details. Shepard admitted to working with Captain Graybiel, one of the authors of the report, but he wouldn’t say anymore. So Morey went to Pensacola and spoke to Dr. Harlow Aides, who had also worked with Graybiel. “It is clear from my personal interview,” he wrote Rhine, “that some of the pilots find themselves out of their body, looking back at their own physical bodies which are still efficiently flying the jet plane.” Other reports followed Graybiel’s. In one, a pilot said “that he was at high level when he suddenly had the feeling that he was outside the cockpit, sitting on the wing, and watching himself fly the aircraft.” In others, the break-off phenomena was experienced as a relatively mild feeling of unreality and separation.

There’s been some recent research that might explain the out-of-body experience. In 2006, one possible physical explanation for out-of-body experiences was found by Swiss neurologist Dr. Olaf Blanke. Blanke discovered that when electric current was applied to the angular gyrus at the temporo-parietal junction in the brain, an out of body experience occurred. Whether or not this explains the break-off phenomena remains to be seen, but behavioral neuroscientist Todd Murphy points out that Dr. Blanke created this experience with one patient only, and this instance does not address the cases where subjects have out-of-body experiences and come back with information that they could not have obtained given the location of their bodies at the time.

Blanke was also not the first. “In the 1950’s, the Canadian neurosurgeon Wilder Penfield also succeeded in eliciting an out of body experience using electrical stimulation,” Murphy wrote in a commentary on Blanke’s results, “but he was stimulating a very different area of the brain, the sylvian fissure. Dr. Michael Persinger has elicited out of body experiences through stimulation of the temporal lobes using magnetic signals derived from the EEG signature of one of the structures deep in the temporal lobes. Clearly, there is not a single ‘brain center’ that supports out of body experiences but rather a widely-distributed set of pathways.” That said, Murphy does credit Blanke’s research. “The experiment goes a long way toward providing a scientific explanation for what some believe is a paranormal phenomenon, even if the study is based on only one patient.”

I believe there’s been even more recent research, but I haven’t looked into it since I was working on this section.

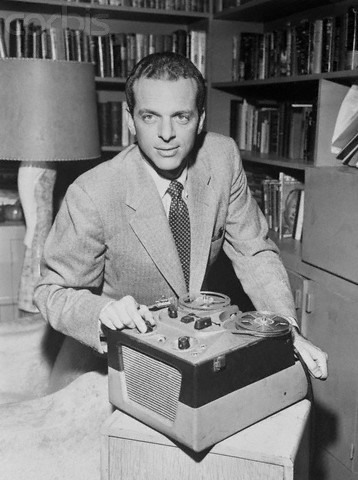

The picture is of Dr. Ashton Graybiel, who went on to have a distinguised career. There’s an Ashton Graybiel Spatial Orientation Laboratory at Brandeis University today. “Dr. Ashton Graybiel, whose studies on the effects of weightlessness and acceleration on human balance, spatial orientation, physiology and performance helped prepare America’s astronauts for manned space flight …” From his New York Times obituary.