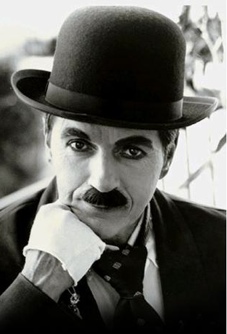

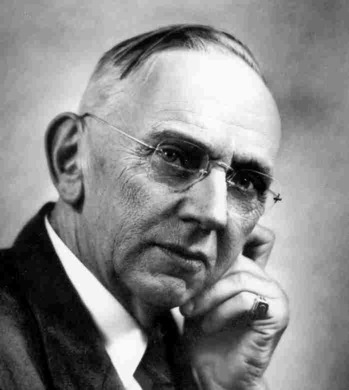

Dr. Arthur Holly Compton

On June 21, 1937, J. B. Rhine wrote Dr. William McDougall, the head of the Duke Psychology Department: “I had a talk yesterday with Arthur Compton, the Nobel physicist from the University of Chicago. He is agreed that no physical theory is applicable, and he is frankly inclined toward a non-physical mode of causation. The friend I have made at Princeton who knows Einstein asked him if he had any theory or way of approach which would make clairvoyance reasonable. He replied in the negative.”

So I knew that Compton was a Nobel Laureate, but there are actually a number of letters to and from Nobel Laureates in the Parapsychology Lab archives at Duke. I guess I was spoiled! I made a note to myself to keep a look-out for letters to and from him and found and copied a few, but I didn’t look as hard as I should have.

Rhine wrote the following about Compton on April 16, 1947. “My only fear about him is that he has too far compartmentalized his thinking so as to be uncritical in dealing with problems that border on religious thinking. From what Eddy tells me he must be pretty uncritical in his deals with mediumship. [Eddy was Sherwood Eddy, the Protestant missionary and author, and someone who Rhine thought of as far too credulous] I have heard other reports leading to the same conclusion. Nevertheless, I think it would certainly be worthwhile to approach him and find out just what his attitude is. I have met him a couple of times …”

They met again in May, 1947 and Rhine’s fears were put to rest. Rhine had heard that Compton had been sitting with mediums, but Compton told him that he’d been asked to take part in a few sittings, and he had, but it wasn’t something he planned to pursue. Rhine happily (and a little triumphantly) wrote Eddy that Compton’s interest in mediums was incidental. “I found that he has a broad-minded and generous scholarly interest in parapsychological investigation. It is an interest that goes back to his undergraduate days. I was greatly pleased to know that this firmly entrenched interest exists in the mind of a man of such high scientific attainment.”

And Compton wrote about Rhine on August 9, 1947. “Altogether, it is my impression that Rhine is the most able investigator of parapsychological phenomena in this country. As you are well aware, it is difficult for an investigator of this field to retain the scientific support of his colleagues. On inquiry within our own Department of Psychology at Washington University, [where Compton was the Chancellor of the University] I find that Rhine, although he has had some difficulties, has been able to maintain the respect of other psychologists for the work he is doing.”

To Rhine he wrote on the same day, “I find great interest in your article on The Relation Between Psychology and Religion [referring to an article Rhine wrote with that title]. I hope to discuss some of the points with you if opportunity arises.” (Compton was a very religious man.)

Here is a Compton bio from the NASA website (where I got the picture of him above):

American physicist Arthur Holly Compton was one of the pioneers of high-energy physics. In 1927 he received the Nobel prize in physics for his definitive study of the scattering of high-energy photons by electrons which became known as the Compton Effect. This work was recognized as an experimental proof that electromagnetic radiation possessed both wave-like and particle-like properties and laid a foundation for the new “quantum” physics. All the experiments onboard the Compton Gamma Ray Observatory rely on the detailed knowledge of the interaction of high-energy gamma-rays with matter that Compton first described.