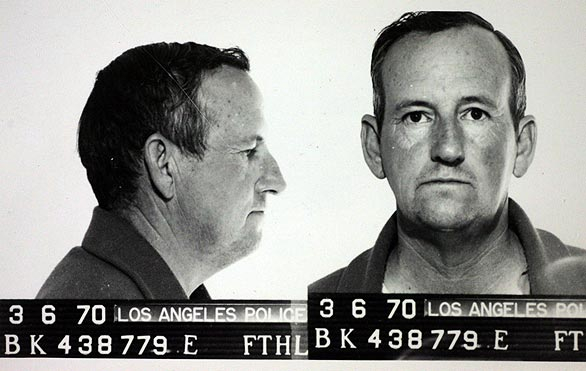

In 1934 the famous medium Eileen Garrett came to the Parapsychology Laboratory and allowed the scientists there to conduct experiments with her while she was in a trance. When she went into her trances another personality who called himself Uvani took over and spoke to the people in the room. Uvani said he was there to manage the communication between the living and the dead, and to protect Eileen, who was vulnerable while in a trance.

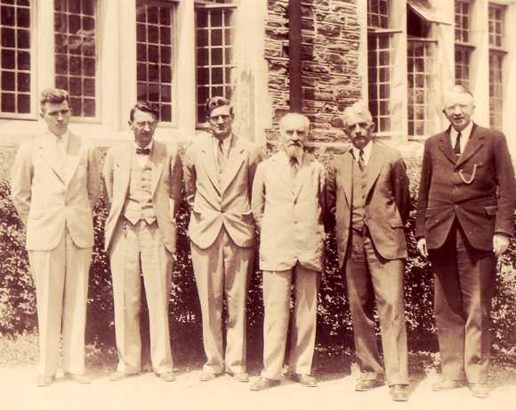

Lots of people participated in these sittings, including the lab scientists themselves, the wife of the president of Duke University, and one of Rhine’s colleagues in the psychology department—fellow professor Don Adams. A secretary recorded everything that was said.

Uvani started each session by describing the sitters first, and it was clear he liked everyone except Donald Adams. He said he felt a lot of negativity when Adams sat down. It was interesting because unknown to anyone in that room at the time, a week earlier, Adams had sent a letter to William McDougall, the head of the Psychology Department, who was in England at the time. In that letter, Adams and two of Rhine’s other colleagues, Helge Lundholm and Karl Zener, did everything they could to undermine the very experiments Adams was participating in that day.

The letter began, “Those of us in the department who have signed this letter are profoundly interested in the continuous work of our group,” and they were writing, “because, as things have developed since you left, it seems to us that grave dangers have arisen possibly threatening the integrity of our group.” The danger was J. B. Rhine. (More below.)

The men said they had evidence that their graduate students believed that in order to progress in the department they had to have an interest in psychical research. Psychical research has a place, they said, but “we do not like to have such research attain a dominance which would exclude the investigation of psychological problems in general.”

The evidence they offered was three students who had expressed concerns. One said he felt his position there might be shaky if he didn’t demonstrate not only an open mind on the subject, but unquestioning faith in their findings. Another said that a number of the other students were aggressively trying to convert them on the subject, to the point where they couldn’t talk to them about anything. They were like a cult. Last, a visiting graduate told them that one of the current graduate students was highly emotional about the subject.

Perhaps getting to the real heart of the matter they said that the whole situation, “is of vital concern to ourselves, and is developing into an increasingly distressing situation; for we depend in our own research work, to a degree, upon the cooperation of our graduate students, and if the latter turn more and more away from the problems of psychology in which we are interested we feel that our work will be greatly handicapped.”

The students “hero-worshipped” Rhine, they wrote. And “he had much closer personal relations with them than professors usually had with students.”

Certainly they, too, made every effort to get students interested in their own work, so the problem seems to be that Rhine was more successful. They went on to say that, “If this reaction gave the appearance of a personal choice, instead of an emotional response to intensive propaganda and persuasion we would feel that we have no right to protest.” In other words, if the students were genuinely interested in parapsychology and weren’t being bullied into it, they wouldn’t be bothering him about the matter. But then they gave an odd example to prove their point. They wrote about a graduate student who they said was pressured into switching to psychical research. But then they quote him as saying, “I regard Dr. Rhine as the most intelligent, most widely read, and greatest psychologist in the world, a Galileo of our age.” Overwrought perhaps, but not unusual for a young person, and in any case, it doesn’t sound like he was coerced.

The three men asked McDougall for advice and hoped that no one would get hurt, but “we are confident that mere admonition will not suffice. We write to you because the future success and happiness of our individual work and the continuance of the present department as a center of psychological research … is severely endangered by the present situation.”

McDougall wrote back suggesting they send a copy of their letter to Rhine. They beg off, saying the students spoke in confidence and while not named, are recognizable. The reason they didn’t approach Rhine directly, they wrote, “was our feeling that adjustment of the specific difficulties could not be reached without consideration of broader departmental policies than could be settled without your guidance.”

McDougall wrote an extremely delicately worded letter to Rhine. He said their colleagues were alarmed, but he doesn’t mention their letter. “It would be a great pity,” he wrote, “that if our endeavor to introduce P. R. [psychical research] into the circle of university studies should go awry through excessive zeal leading students to neglect all the more orthodox parts of psychology in favor of P. R.” We need to proceed more slowly, and perhaps more diplomatically.

Adams, at least, felt pangs of conscience about his actions. Two years later he wrote an essay called “The Natural History of a Prejudice.” It’s an amazing document and he makes some pretty astonishing admissions. While allowing that Rhine’s statistics, “… seemed impeccable and his gradually more rigorous conditions adequate,” Adams admits that nonetheless he longed for Rhine to fail. “I wanted not the truth, but to prove his positive conclusions wrong.” Whenever paranormal investigations had negative results, Adams wrote that he felt relief. “I would have been disappointed instead of delighted at discovering a new phenomenon …” He described how his colleagues would come up to him at meetings and conferences and “ask immediately�—and hopefully—whether Rhine was crazy, duped, or crooked.” When Adams replied that Rhine was none of these his colleagues treated him with contempt. “Science, with a capital S, has no prejudice, but individual scientists have,” he confessed. (More below.)

When looking back at his behavior towards Rhine, Don Adams wrote with incredible and admirable honesty. “Have you ever had the experience of seeing a belief, that you have considered fundamental to everything you value, gradually but inexorably undermined? … I have never had much sympathy for the embattled Fundamentalists, but since facing a situation comparable in many ways to theirs and finding that I behaved just as badly, their conduct no longer seems so strange.”

Adams showed his essay to Rhine, which was again, admirable, considering how snarky it gets in places. In one section he wrote, “My colleague, J. B. Rhine, who had been a competent plant physiologist, but was still not much of a psychologist …” Adams crossed out the part which read “but was still not much of a psychologist” but it was still clearly legible. By the way, I would read things like this over and over, this attitude that Rhine wasn’t a real scientist because his PhD was in botany. It was like a prejudice within a prejudice.

Three times in the essay Adams called Rhine a schemer. “Rhine himself, though neither a liar nor a fool, was a scheming fellow. To be sure, any intelligent person who has been poor is likely to be …” And later, “I really believe he schemes in his sleep.” (I have to admit I cracked up when I read that.)

I thought Rhine showed enormous self-possession and insight when he read those sections and instead of clocking the guy, he asked, “if a schemer is not simply one whose constructive planning is not favorably regarded?”

Adams sums it all up best when near the end of his essay he wrote, “there is a sort of inexorability about scientific method before which prejudice is silly, small-minded and futile. Nature does not seem to care in the least what we think of her.”

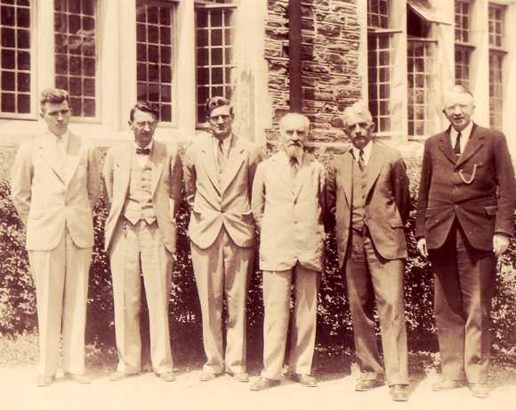

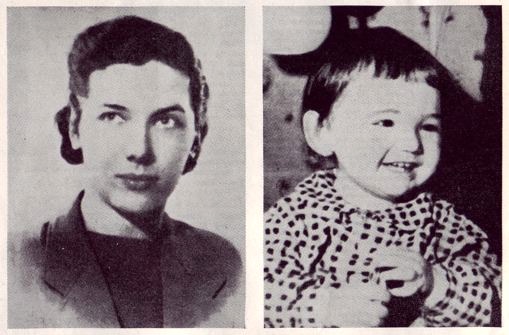

The first picture is Eileen Garrett, the second is William McDougall and J. B. Rhine, and the third is J. B. and his colleagues in the Psychology Department. From left to right: J.B., Don Adams, Karl Zener, William Sterne, I don’t know who the next guy is, Helge Lundholm.

[The source for the essay quotes: Donald K. Adams, “The Natural History of a Prejudice,” Archives for the History of American Psychology, University of Akron.]