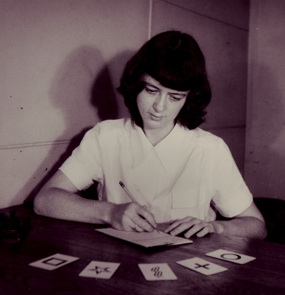

This is a picture of the medium Eileen Garrett. She helped secure the initial funding that established the Parapsychology Laboratory (from Francis Bolton, who I will post about later). Garrett also put herself at the lab’s disposal for any tests they wished.

I liked collecting her descriptions of her trance state. She was smart and articulate, and they give an interesting peek into the process.

“I conceive of yesterday, today, and tomorrow as a single curve … time loses reality and the past and present and future are present in one instant.” Then she writes how either thoughts, images or sounds come to her, and while she calls the process indefinite, it’s “almost electric in its reception. One knows.”

In an article in Tomorrow magazine, where she’s talking about ghosts, she says they don’t always appear as spectres, “but often as warm, living breathing people. Where are they?” And that’s where it got really interesting to me, because she didn’t just see ghostly people, but also buildings and places and woods that were no longer there. “… into the purple, more intense than all, I see rare plants and all kinds of growth, and then I am unable to find any words that could translate this experience …”

It’s always frustrating how ghosts never really have anything substantive to say. But Garrett said that “much of importance is transmitted,” but we neither understand what is seen or have the ability to translate it. I had trouble penetrating some of the messages she communicated, but I would love to get someone like the Dalai Lama, or, more realistically, a similarly educated Tibetan monk, to take a look at them.

Garrett was open to all possible explanations for her visions. Were they discarnate beings? Or was she crazy? At least she had a sense of humor about it. She once quipped, “on Monday, Wednesday and Friday I think that they are actually what they claim to be … on Tuesday, Thursday and Saturday, I think they are multiple personality split-offs I have invented to make my work easier … on Sunday I try not to think about the problem.”